When William Peter Blatty was a high school student at Brooklyn Prep, one of his Jesuit teachers told the class about a 14-year-old boy in Maryland who was said to be a victim of demonic possession. Blatty read about the story in a Washington Post article dated August 20, 1949. The Post quoted sources from the Catholic diocese of Washington D.C. “In what is perhaps one of the most remarkable experiences of its kind in recent religious history, a 14-year-old Mt. Rainier boy has been freed by a Catholic priest of possession by the devil.”

The article recounted strange tapping on the walls, profane utterings, words appearing on the boy’s chest, projectile vomiting, extraordinary feats of strength, objects flying around the room and levitation. Doctors subjected the boy to medical, pharmaceutical and psychiatric treatments. Nothing worked. As a last resort, the family’s Lutheran minister recommended they consult the Catholic Church who had experience with exorcism.

The Church conducted an investigation and determined the case to be an authentic instance of demonic possession. The boy was moved to Georgetown University Hospital. Archbishop Ritter (soon to be a Cardinal) appointed a young priest, Father Albert Hughes, as exorcist. The boy tore a metal spring from the hospital bed and slashed Father Hughes down his shoulder and arm. The wounds required 100 stitches. Father Hughes suffered a nervous breakdown and quit.

Archbishop Ritter moved the boy to Alexian Brothers Hospital in St. Louis. He appointed Father William Bowdern, 56, and six other priests to take over the exorcism. According to the Post, the boy was cured by the exorcism. He had no memory of the events that happened to him.

Blatty went on to study literature at Georgetown University. In 1954, he moved to Los Angeles where he submitted humorous stories to magazines. He ghostwrote books for Zsa Zsa Gabor and Abigail Van Buren (Dear Abby). He became a contestant on the Groucho Marx quiz show You Bet Your Life and won $10,000. This allowed him to devote his life to writing.

From 1963-66, he wrote four critically acclaimed comic novels. His narrative style was compared favorably to S. J. Perelman, but book sales were poor. Film director Blake Edwards hired Blatty to write screenplays for A Shot in the Dark, Gunn and What Did You Do in the War, Daddy?

On New Year’s Eve 1969, Blatty attended a party in Sherman Oaks at the home of novelist Burton Wohl. There he ran into the editor of Bantam Books, Marc Jaffe. Jaffe asked Blatty what he was working on. Emboldened by a few cocktails, Blatty blurted out the story of a child possessed by a demon. Jaffe said, “I’ll publish that.” Blatty signed a contract and was given a $10,000 advance.

Bantam was unable to acquire the rights to the original story so Blatty had to fabricate details. He researched all he could find about possession but there wasn’t much. His old Jesuit high school teacher put him in contact with Father Bowdern, the man who presided over the actual exorcism. Father Bowdern was 71 and still lived in St. Louis. He and Blatty began a seven-year correspondence.

In Father Bowdern’s first letter to Blatty, he wrote: “I can assure you of one thing: The case in which I was involved was the real thing. I had no doubt about it then, and I have no doubt about it now.” He told Blatty he’d be glad to assist him with the book as long as they maintained the victim’s anonymity.

Blatty wrote the novel at his ex-wife’s Encino guesthouse. He worked from 11 at night until sunrise, writing three polished pages a day. “This one venture outside of comedy was going to be it for me—this story that had been festering inside me for twenty years. I’ve got nothing else to do but collect unemployment. No excuses. My hope was that it would be reviewed with respect, that I wouldn’t be mocked, that’s all I was hoping for.”

Blatty’s initial concept was to write a spiritual detective tale about a young boy accused of murder who uses demonic possession as a legal defense. This would allow him to explore the history of exorcism. He had no intention of writing a scary novel. As he fleshed out the story, the 14-year-old boy became a 12-year-old girl. He moved the story from St. Louis to Washington D.C.

Actress Shirley MacLaine, a friend of Blatty’s, was the inspiration for the girl’s mother. Blatty based the older priest, Father Merrin, on an archaeologist he met in Lebanon named Gerald Lankester Harding who helped discover the Dead Sea Scrolls. Father Karras, the younger priest, was based on Blatty himself. Blatty was a Roman Catholic who had a crisis of faith after his mother’s death in 1967. He described his faith of that time “as more of an intense hope than a solidly held belief.”

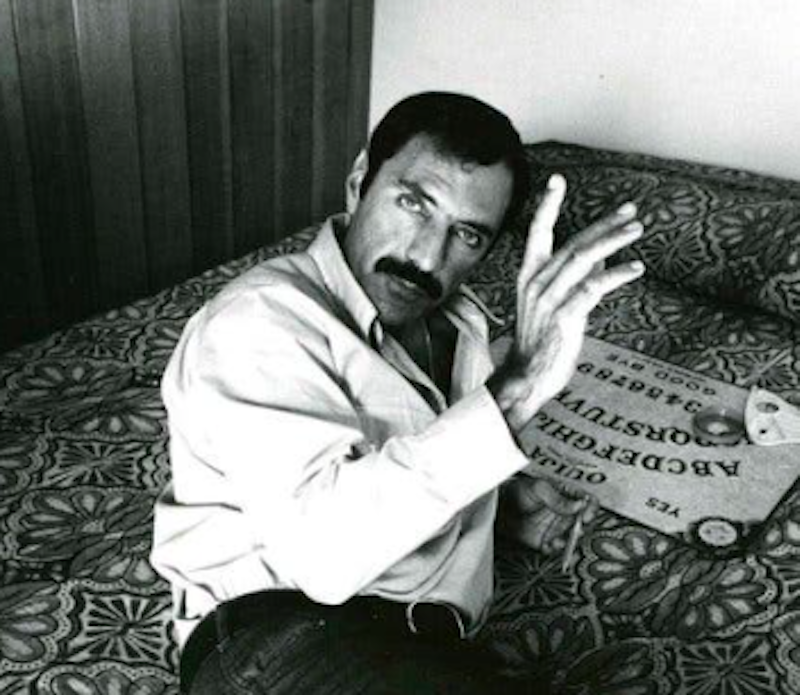

The evil statue of the demon Pazuzu who possesses Regan, the 12-year-old girl, was based on a statue Blatty observed in a museum in Mozul, Iraq. The inciting incident of the Ouija board came from church doctrine about avoiding the occult. Throughout the book, Blatty refers to the absence of the girl’s father. He intended the story to be an allegory about the devastation wrought by divorce and the breakdown of the family unit.

Blatty finished the novel in nine months. It debuted in June 1971 to rave reviews. But book sales languished. Blatty was booked for a five-minute publicity segment on The Dick Cavett Show. The first guest cancelled and the second was drunk. Blatty was the sole guest for the entire show. Cavett greeted him by saying, “I’m sorry Mr. Blatty, I haven’t read your book.” Blatty replied, “Then may I tell you about it?”

For the next 40 minutes Blatty went on an engrossing dissertation about possession and exorcism. Cavett’s only question was asked with irony. “Mr. Blatty, do you really believe in the existence of Satan?” Blatty replied, “In every society there is mention of an evil magician that spoils the work of the creator.”

After the Cavett appearance, The Exorcist became number one on The New York Times bestseller list for four months. Warner Brothers bought the film rights for $600,000 plus 37 percent of the net profits. Blatty would produce and write the movie. The resulting film is considered the scariest movie ever made.

In the acknowledgements to the book, Blatty thanked his English professor “for teaching me to write” and the Jesuits “for teaching me to think.” He wanted to make an argument for God and hoped to help people with their faith. “I was trying to get across that this is not a horror story. This is real. It is a great mystery that providence should permit diabolical activity, but we know that God works for good with those who love him.”

Blatty died in 2017 at age 89 of multiple myeloma. He remained a devout Catholic to the end.