This is a sticky one. All the victims so far have been white men, true even of the Muppets, although the whiteness in that case is leavened by the silly voices. I’m a white man, and if I start saying that this or that Latina or black woman sucks, I'm doing it from a privileged position, and it might occur to someone that it’s precisely the race or gender of the person in question which makes me think they suck. That would be a problem.

Statistics confirm that white men suck at an 84.3 percent rate, which is considerably higher than that of any other identifiable group, with the exception of people who work in the entertainment industry. Privilege yields many opportunities to be intolerable, even as people keep purporting to admire you. Just think about the Presidents of the United States, by which I mean the pantheon of white male jerks who’ve governed us, not the awesome punk band that did "Peaches." But though women and members of various minority groups, and people who are both, suck at lower rates than my own people, they do suck. We are all members of the same species, and it’s a species that blows: extremely, continuously, and irremediably.

As long as I keep cracking only on white guys, I can't be accused of being a racist and sexist, whatever my inmost beliefs. Not being called a racist or sexist has been the primary goal of my life. Critiquing my own people and our debased culture, I have great credibility, like Bill Cosby attacking hip-hop circa 1995. Attacking your people, I'm a mere oppressor. But I don't want anyone to feel left out. "Why They Suck" welcomes everybody; it’s indiscriminate, we might say. I’m an equal-opportunity destroyer. Or at least, I'd feel bad without including a token black guy and a token woman or two, who will arrive in due time. Diversity is my watchword.

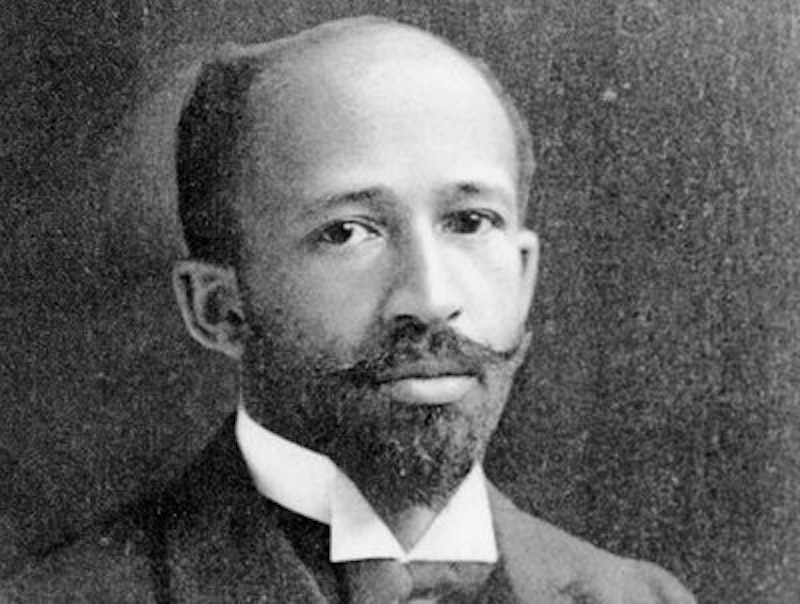

One thing that's necessary in this case but less so in other cases, therefore, is a series of disclaimers. W.E.B. Du Bois' sociological study of black communities in Philadelphia was groundbreaking, as were his histories of John Brown’s raid and Reconstruction. There were few black intellectuals working at his level when he started out, and he overcame unbelievable barriers to do what he did. But there are a number of significant problems.

Early in his career, he was a racial essentialist, buying this structure of thought from European racists such as Gobineau. “The history of the world,” wrote Du Bois in 1897, “is the history, not of individuals, but of groups, not of nations, but of races, and he who ignores or seeks to override the race idea in human history ignores and overrides the central thought of all history.” Then he argued that black people are inherently spiritual and artistic (musical, for example). He was reversing stereotypes, sort of. He was endorsing them as well.

Du Bois ditched the racialism later on, but endorsed Marxism in its stead. He eulogized Stalin, praising the great cleanser (who, for example, exiled the entire nation of Chechnya to Siberia) for overcoming ethnic divisions in the Soviet Union.

Joseph Stalin was a great man; few other men of the 20th century approach his stature. He was simple, calm and courageous. He seldom lost his poise; pondered his problems slowly, made his decisions clearly and firmly; never yielded to ostentation nor coyly refrained from holding his rightful place with dignity. He was the son of a serf but stood calmly before the great without hesitation or nerves. But also—and this was the highest proof of his greatness—he knew the common man, felt his problems, followed his fate.

In Du Bois' conflicts and rivalries with Booker T. Washington and Marcus Garvey (the three might have been the pre-eminent leaders of African America, 1890-1925), there’s an explicit elitism, often interpreted by his opponents, and hinted at by himself, as tracking skin tones. Du Bois argued that "the race" would be uplifted and redeemed by a "talented tenth" who could ascend through white educational institutions, whereas both Washington and Garvey emphasized internal development of the whole black community.

Du Bois called Garvey, who at the time led the largest political movement in the African diaspora that had ever existed, "a little, fat black man; ugly, but with intelligent eyes and a big head." When Garvey was jailed after a long vendetta against him by J. Edgar Hoover, Du Bois went with Hoover. "No negro in America ever got a fairer and more patient trial," he wrote. Garvey "convicted himself with his own monkey-shines in court." Garvey gave as good as got, characterizing Du Bois as (sorry) a "white man's nigger" and "an enemy of the black people of the world."

One problem with the figure of Du Bois is that he’s canonized in anti-racist and multicultural education, which often makes itself easy by choosing one or two texts and authors, emphasizing them relentlessly for decades during X history month, and ignoring every other figure emerging from those groups. You might be left under the impression that Du Bois and King were pretty much the only black activists or intellectuals of the 20th century. Many colleges force everyone to read The Souls of Black Folk and spend the rest of the year congratulating themselves for inclusivity and understanding of the race problem.

But Du Bois in his literary mode is a mixed bag, at best. Part of the apparent power of the basic ideas of that book—above all the alleged "double consciousness" of African-Americans and the "veil" separating the races—emerges from their very elusiveness. They support a rich variety of solemn interpretations. That may be because they are both vague and extremely problematic, and I think their generality and amorphousness is precisely the source of their prestige. They give the illusion of providing profound insights into the American racial situation, and though a number of black intellectuals have provided interesting interpretations of double consciousness, a number of white intellectuals have thought that the notion gave them access to the mind of black people, which is pretty silly. Frederick Douglass was sharper on the phenomenology of race, and a better writer. Garvey was sharper. Zora Neale Hurston was sharper. Malcolm X was sharper, as was James Baldwin.

At his worst, Du Bois committed some of the purplest prose in the history of English. It runs in and out of his essays, and dominates his novels, which should only be read by scholarly completists.

Amid this mighty halo, as on clouds of flame, a girl was dancing. She was black, and lithe, and tall, and willowy. Her garments twined and flew around the delicate moulding of her dark, young, half-naked limbs. A heavy mass of hair clung motionless to her wide forehead. Her arms twirled and flickered, and body and soul seemed quivering and whirring in the poetry of her motion.

As she danced she sang. He heard her voice as before, fluttering like a bird's in the full sweetness of her utter music. It was no tune nor melody, it was just formless, boundless music. The boy forgot himself and all the world besides. All his darkness was sudden light; dazzled he crept forward, bewildered, fascinated, until with one last wild whirl the elf-girl paused. The crimson light fell full upon the warm and velvet bronze of her face—her midnight eyes were aglow, her full purple lips apart, her half hid bosom panting, and all the music dead. (The Quest of the Silver Fleece)

Dark Princess, another of his novels, could be used as an anthology of approaches that young writers of all colors and creeds should avoid at all costs. Perhaps in the next few decades, we could identify another "representative of his race" to carry the absurd burden we have piled on W.E.B. Du Bois.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell.