This story begins in the cold evenings of December, when the scent of biscuits mixes with smells of soups, and when even the exhausts of cars have something joyful about them. It all begins with that privileged combination of smoking stoves and fireplaces, people on the move, warm radiators and red traffic lights reflected on the car windshield—and the icy droplets refracting and reflecting those lights in the most disparate directions. This potion of sensations is the magic of Christmas.

This incredible strength, inexplicable when you are little, begins in that moment of community life. It begins with the curious gaze of one who observes the incessant motion of busy people and figures out all the possible directions—the reins that determine our actions.

People touching each other, carried away by the warmth of your family, by your grandmother’s rusty driving. You feel part of something bigger than yourself.

And although Christmas is a social construct, that breath of belonging is what every child, every person desires. It’s that desire for equality, for community. It’s the same pulling force that has turned peoples to fascism and has created wars, social monsters and, paradoxically, inequality. But any cultural invention, such as Christmas, is certainly not the reason for these social aberrations, because human emotions can equally lead to beauty and horror.

In every culture, people approach one another, celebrating holidays of all kinds, worshiping divinities or begging the forces of nature for mercy. But they do it primarily to satisfy a natural need, to be with each other—close and safe. And Christmas is about the warmth of one person close to another, a sofa and a boiling pot, generations aligned in a single moment of history—of flour and salami.

But Christmas isn’t really magical. It’s the simple manifestation of emotions already shaped in our biological consciences: Christmas is an excuse that brings out that joy, already lived and branched out in the nerve endings of every child. It’s an intrinsic attribute of every individual of our human civilization. And it can be shaped: it can be Christmas, or any other religious holiday belonging to other cultures. It can also be your homeland, war or common hatred.

And in the Christmas context there’s Santa Claus, or baby Jesus, depending on the cultures. Who come, with a sleigh and reindeer, to bring the gifts on Christmas Eve. They enter the fireplace when you sleep and, magically, when you wake up, there they are, the gifts. And the reindeer also ate the cookie you left the night before. Then you unpack the presents, and find the surprises. That game you wanted so much, and the one you didn’t know you wanted. Thanks, Santa Claus!

This is the time when, in our minds, “social Christmas” takes the place of Christmas itself, or, as I’d call it, “natural Christmas.” During the first years of our life, the joy of being together becomes inextricably linked to social dynamics (including receiving gifts, or lighting candles) and to a fictitious character with a white beard, or semi-deities incarnated as flying babies who deliver tangible gifts to homes around the world.

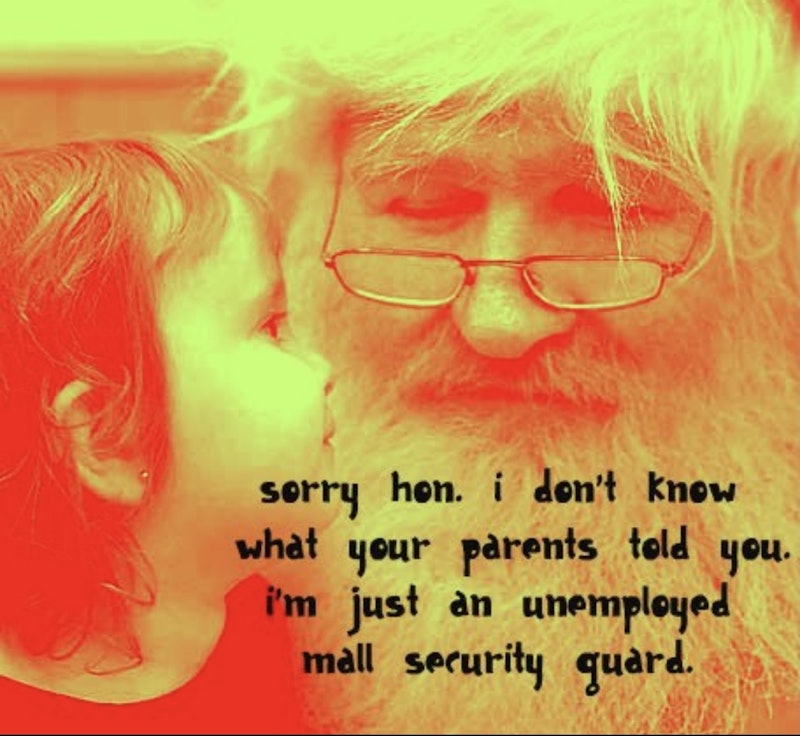

One day, however, something bad happens. On a day in late November, at school, while you start to let yourself be tickled by the idea of Christmas, you ask your classmate what gifts he thinks Santa will bring him this year. He turns, with a mocking look, and reveals to you: “Santa Claus doesn't exist.”

In that moment you run to the teacher and tell her that your friend told you a lie. She replies with an ambiguous “My dear, everyone believes what they want.”

You never forget the day you discover that Santa Claus doesn’t exist. It’s the day you understand that you’ve been betrayed, confused, teased and humiliated by the people you care about the most. And it’s only the beginning of a process, one that makes you discover the world around you, with its weaknesses, its wickedness and violence; with its arbitrary assumptions and constant betrayals.

Santa Claus disappears. It leaves an indelible mark; it’s the first real trauma. It’s the betrayal of your parents, grandparents, and uncles. It’s the deception and falsity of a story that doesn’t exist. If it were a life lesson, we’d believe it. But it’s not so. Perhaps, “life” begins with these first betrayals. Perhaps, the weaknesses of our civilization arise from genuine attempts to make the little ones among us happy, by removing them from the difficulties of our adult lives.

However, the happiness of a child doesn’t lie in Santa Claus, in the flying reindeer or even in gift packages. Nor does that joyful feeling need to be stimulated or induced. Happiness is the essence of a child, and Christmas is its natural exaltation. A child’s mind is still devoid of trauma and is free from any vision of things, any definition that has been inculcated in us, without our consent. But we’re mostly unaware of it. And for this reason, we create nonsense to make children happier, to free them from chains that don’t actually exist. And by doing this, we are instead giving them a ball and a chain for the rest of their days.

There are those who, faced with this objection, would say that Santa Claus, at least, stimulates the imagination of children. But even this is false, since there’s no correlation between a child’s ability to fantasize and his or her belief in Santa. Fantasy stories can stimulate the imagination and creativity, but it must also be clear for the child that they represent a non-reality, a detached world. Betrayal and deceit don’t stimulate the aforementioned desirable attributes.

The happiness of a child is in the freezing December snow, and in the warmth of your grandparents clinging to you while sitting at the table. This is Christmas, and this should remain. Santa’s betrayal is unnecessary.

When I see my two-year-old son running excitedly around the table in the evening, without any knowledge of the bearded man, I understand that there’s no space for Santa in my little family. He’ll know that his grandmother tells fairy tales—and that she loves him. He’ll know that Santa Claus doesn’t exist, but that he must respect the decisions of others and not reveal it to his friends.

I don’t want to betray my son. That’s why Santa Claus won’t be bringing gifts to our house—mom and dad will. Or his grandparents and friends, because they decided to make him feel special for a day. They decided to make him feel special, not a bearded man who flew from Lapland. Because in order to fly, and get excited, it takes very little, for a kid. And as we grow up we forget it, betrayal after betrayal.

If we want to educate our children to be happy, let’s forget these social jokes, and instead focus on what we really need (everyone, not just the little ones)—closeness, affection and a sense of belonging.

—Federico Germani is a writer and bioethicist at the University of Zurich, Switzerland. He’s the founder and director of Culturico. Twitter @fedgermani.