In the last few years, a trend among critics and contemporary writers is questioning the merits of writers that are part of the literary canon. The prose is not considered as good as when it was first received, the writer is overrated, or his personal life is a mess. It’s easy to point out flaws of a writer, or even hate them. Especially a writer that’s dead and can’t really defend himself. Ernest Hemingway hasn’t been spared.

Those critics and readers focused on Hemingway’s writing style will say that the whole “iceberg method” is just too easy and laughable and anyone can do it. Nobody should write in short, declarative sentences. Instead, we should indulge in the use of the English language.

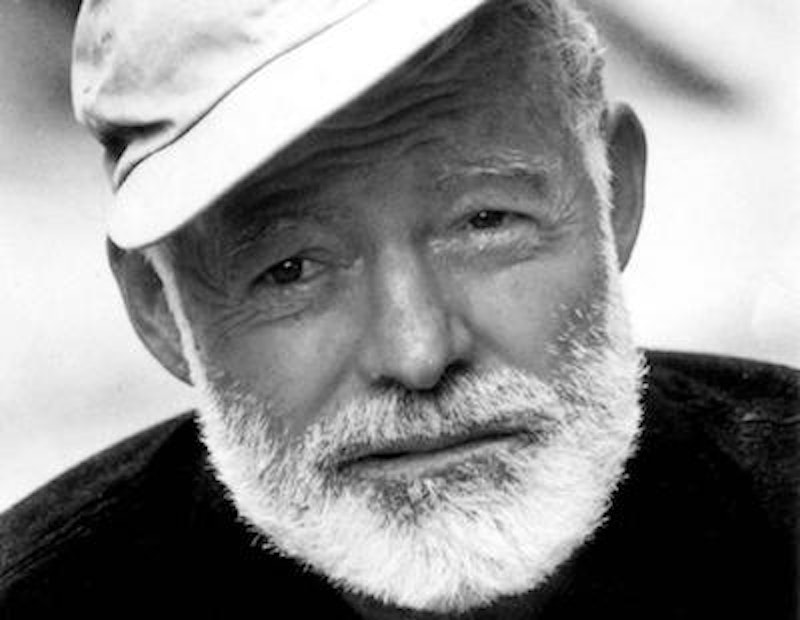

Then there are those who get obsessed over Hemingway’s maleness. It’s a known fact that Hemingway had plenty of issues with his own masculinity. We certainly have numerous photographs of a bare-chested Hemingway, trying to prove his manliness. Critics speculate that he was gay and by being overly masculine was just a way of masking his desire to be with men.

That ridiculous and hate-filled term “toxic masculinity” wasn’t in use during Hemingway’s time, but if he lived today, he surely would be accused. One wonders whether he’d be issuing sarcastic apologies on Twitter.

All of these criticisms are fairly obvious and we’ve heard them repeatedly. Some may be true. I’ve no clue if Hemingway was gay or not, or whether he had secret desires. I’ve no interest in putting the fictional Hemingway on the couch and psychoanalyzing him.

One of the fascinating aspects about Hemingway is the authenticity of his prose. Hemingway’s athletic words seem like they’ll run off the page before you even read them. He doesn’t dwell. He’s not Tolstoy or Proust. But he does wonder about the interior lives of his characters and indirectly himself. He wonders where they’re going and where they’ve been, and how they’ll get where they need to go in the hope that they won’t be doomed or lost. He understands the essence and most importantly, the nuances of the human condition. He understands that we’ll never really get under the skin of our fleeting states of being because we’ll always want to escape our very selves.

In one short paragraph, you’ll feel the rain in Paris and the angularity of the café tables even if he never really tells you the exact details. In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway writes: “Then there was the bad weather. It would come in one day when the fall was over. You would have to shut the windows in the night against the rain and the cold wind would strip the leaves from the trees in the Place Contrescarpe.”

Describing the café at the bus terminal, he writes: “It was a sad, evilly run café where the drunkards of the quarter crowded together and I kept away from it because of the smell of dirty bodies and the sour smell of drunkenness.” It doesn’t matter what these dirty people drank. Maybe the smell of alcohol will be different for all of us, but we can create a mental collage of offensive smells as if they’re descending with the weight of the world on us, suffocating every pore of our being.

Despite the cold clarity of Hemingway’s scenes, there’s never anything sterile or nihilistic about them. His words don’t bring warm and fuzzy feelings, and why should they? Why should we hide behind the masks of a saccharine avoidance of good and evil? Why should we keep whistling past the cemetery as if the dead don’t exist in the air that we take in? Why should we hide from death itself?

Hemingway’s being and writing are inseparable. I believe it takes courage to write—to really write, to remove the pretenses and stand face-to-face with truth. Hemingway had that courage. It’s difficult to fully understand the extent of his internal suffering and the sad end of his life. But even if the light went out at the end, he was always seeking to write that “one true sentence.” To see directly in the eyes of humanity takes a special kind of guts. Hemingway had that resolve and freedom and fearlessness.