A recent trip to my hometown in Ontario on Lake Huron highlighted the reality that it’s not the travel or our families, but confronting our past that rubs hardest. This is similar to realizing, as adults, that an oft-climbed tree is not the huge specimen (or challenge) we thought as a child. Everything seems smaller, in scale and significance, because we see the reality, not the fantasy.

Childhoods are, and should be, filled with fantasies; with things that seem grander and better than they are. Adulthood too often rushes at us, regardless of age or size, and in one stunning moment, backhands us into a new, adult way of perceiving the world. On the recent trip to my hometown, that cathartic moment reappeared in my mind as suddenly as it happened to me as a child. And, just as stunningly.

Many can describe our hometowns or neighborhoods in a few simple words. Generally, those words are accurate and satisfactory. My hometown is a small, rural town. Those words create a nice picture: neat, tidy, provincial and pastoral. However, my hometown also had a heavy manufacturing plant, a port and a mine. Different images now come to mind: gritty, tough, often poor; and rough, young men living a transient, devil-may-care, lifestyle.

This was a town of opposites too small to have a poor neighbourhood on the other side of the tracks. Here those opposites were haphazardly mixed together, cultivating jealousy and promoting hate. Here white-gloved mothers, walking to church on Sunday mornings, shooed their children away from the men walking jauntily out of certain “colourfully decorated houses” (a local euphemism) and other men walking, green-faced and dishevelled, out of cheap roadside taverns. Those children learned from their mothers to giggle at the “less-fortunates” who “didn’t know any better.” As little kids, my friends and I learned a different lesson: be out of the house when these men got home and their hangovers really set in.

We saw our futures in these men. Men who grew up in the same neighbourhoods and schools; played the same games; shared the same last names. Men who grew up following in their fathers’ bootsteps; toughened by the prejudices, scorn, and envy created by the invisible but carved-into-stone social hierarchies of a small town. For these men, toughness was the only standard they had.

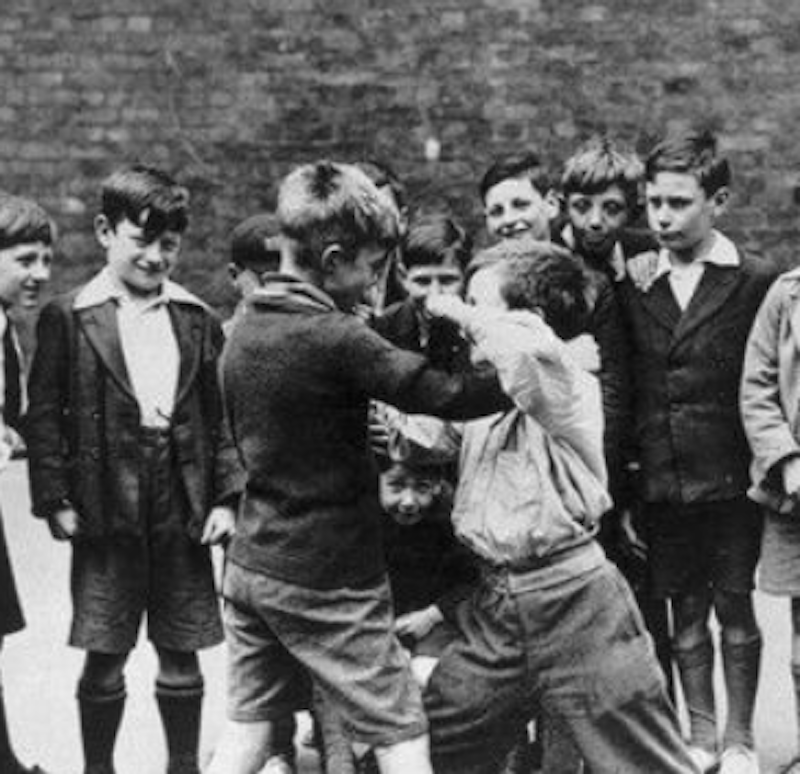

As little kids, my friends and I were recognized and treated as poor. And tough. The poor part is tedious, the toughness we wore like a badge, exhibiting it proudly and boldly. It was currency in my town; you had to have it. And you took it from someone else. We preyed on kids we knew weren’t as tough; and were victimized in turn by those tougher than us. We learned how to “lay one on” other kids whether we were playing baseball, football, hockey or simply fighting. Toughness was a measure of what you were, where you stood and without it, well, you didn’t want to be without it.

We’d often play outside with other little kids. Common enough in that place and time. We played these games with and against other little kids but we knew the differences. We knew the rich kids and they knew us. We knew who had a big house and who lived in halfers, the one-and-a-half-story cottages built for workmen. These games were an opportunity to display toughness. The competition was more than fierce, it was savage. We despised each other for the same basic reason: money.

The same rules applied, more or less, to the young teenagers we called “big kids” and the “older guys” in their later teens and early 20s. Why wouldn’t it? It had applied to them when they were little kids and stayed with them all the way through adolescence into adulthood. Regardless of age, being mixed together fuelled the competition, the hatred and need to prove your toughness. As little kids we proved it in sports; for the older guys, the competition evolved to fighting. With fists. Fighting with a weapon simply meant you were good with that weapon, but it didn’t mean you were tough. Fist-fighting allowed a guy to prove he could take the deep thud of fractured ribs or the sharp crack of a broken jaw, and still win.

We wanted to be just like the big kids. We wanted a blue and white varsity leather jacket, with gold championship patches running up each arm, just like theirs. We wanted a girlfriend, just like theirs, one that would hug and kiss us as we came off the field or rink after another victory. The community instilled this in us. We used to get time off school to watch their football games. Sitting on the grass near the sidelines, we could feel the ground tremble as they ran by, in rank-and-file, huge in their shoulder pads and helmets. We got to stay out late, on school nights, to cheer maniacally when they flew halfway across the hockey rink to “lay one” on opposing player, with a body check, usually spiced up with an elbow and stick.

We wanted to be like the big kids, but, we idolized the older guys. We gazed awestruck at them after hearing they had “laid one” on another older guy. By fighting, and winning, they not only gained our reverence, but earned a reputation with other older guys. What’s more, they gained the acceptance of men from the neighborhood.

We saw what the older guys did and had, but because we were kids, didn’t see the path they were on. These guys weren’t shining products of an efficient educational system. By 17 they’d worked a few summers in the plant, mine or on the ships. Most managed to graduate high school only after a plant supervisor, or ship’s captain, paid a visit to the school principal. The principal would always add a few points to their grades knowing full well what could happen to his own relatives who worked at the plant, mine or on the ships, if he didn’t “support the neighborhood.” After a couple of years’ of intermittent work, they were married or shacked-up, fathers of one or two kids who’d be raised in their daddy’s bootsteps. By their 30s, they, like other men from the poorer parts of town, lived “a challenging life” on the edge of poverty and alcoholism. A one-lane life with few options and little hope.

Everyone from our age on up hung out downtown on Friday and Saturday nights. We rode our bikes, the big kid walked and older guys drove cars. They cruised in low gear at slow speeds through downtown, loud music blaring from eight-track players (we were too far from anywhere to pick up good music on the radio). They’d drive around for a few circuits, then park and walk into what we called “socials.”

Socials were taverns with a front room that usually held a pool table or two. Socials weren’t dark, dingy, smelly places. Outside they were plain, but when the door opened, bright light streamed out into the night with music and the smell of beer, cigarettes and assorted perfumes trailing along. While you had to be of legal age to go into the tavern and drink, you just had to be out of elementary school to get into the front room where almost anyone could play pool, eat spectacular homemade hot dogs with caramelized onions, or just lean against a wall and watch the goings-on. At 12, my two best friends and I were too small to fight for a spot at the pool tables and too poor to eat hot dogs, so on our trips to a social, we leaned against the wall. As we saw it, the older guys had it all; they were at the top of the social heap. They had jobs. They had money in their new jeans. $10 and $ bills. They strutted around downtown like they owned it. They walked into a social and their favorite drink was waiting for them on the bar, the bartender winking at them that it was “on the house.” They flirted with perfumed girls in short-shorts and low-cut blouses who looked directly, and invitingly, at them. Stuck in the hormonal purgatory of pre-teendom, we leaned against that wall and got a taste of our own futures. A taste we liked.

We hit all the socials that summer. After a few weeks we knew the bartenders and the girls working in them. We knew who hustled at the pool tables and how to sneak into the tavern to quaff a juice glass of draft beer without getting caught—yelled at and chased, but never caught.

One hot, humid Friday night my two friends and I rode downtown. We parked our bikes in a narrow alley and strolled into a social only to immediately be pushed back out by a crowd rushing out the door. We stumbled and got shunted off to the side of the throng. Two older guys were in the middle of the crowd, loudly insulting each other about their heritages and what they did with their mothers.

The crowd began to form a circle. Being small, we squirmed our way to the front and watched as punches flew. Then, one guy swung and connected with the other’s ear. This was not a clumsy drunk swinging wildly, but an aimed, well-timed punch. The first fight in Fight Club showed how much this kind of punch hurts; this one split the guy’s ear. But he didn’t go down. He crouched and when his opponent stepped in to finish him, he uncoiled like a spring, the power generated in his legs and hips shooting right out of his fist. His knuckles crunched into his opponent’s chin.

The force of the punch spun the opponent around and he dropped like a sack of wet mud. The limp thud of his body hitting the pavement was gruesome but it was the ungainly angle of his head that prompted the bartender—who’d taken a few bets on the side—to call the ambulance.

The sack of wet mud was on laying on his front. But we could all see his pale face turning whiter. A girl wailed, “Oh! Look at his head.” I didn’t understand. His head was twisted around so his chin, impossibly, pointed up. I looked at the stunned faces around me, and then began to understand.

Looking at him was like looking down into the narrow end of a funnel; everything else disappeared. The shock of cause and effect wore off and, all by itself, became a message. And, I got the message. Like a car coming at you through thinning fog, the realization hit me at full speed, My friends stayed behind. I left. I walked to the alley, and looked down it. The dirty, stained bricks narrowing like that funnel to an inevitable destination. Then I hopped on my bike and rode home. It took a long time to get home, the rest of my childhood.

On my most recent trip back, I met one of my two friends who were with me that night. While walking through downtown, we stopped in front of that social, which had morphed over the years into several different kinds of business, most recently a marijuana store.

We looked at the door and I looked down the alley. After a quiet moment, my friend said, “Whenever I come back, I stop here. Just for a moment.” I replied, “You’re lucky you only stop here when you come back.”