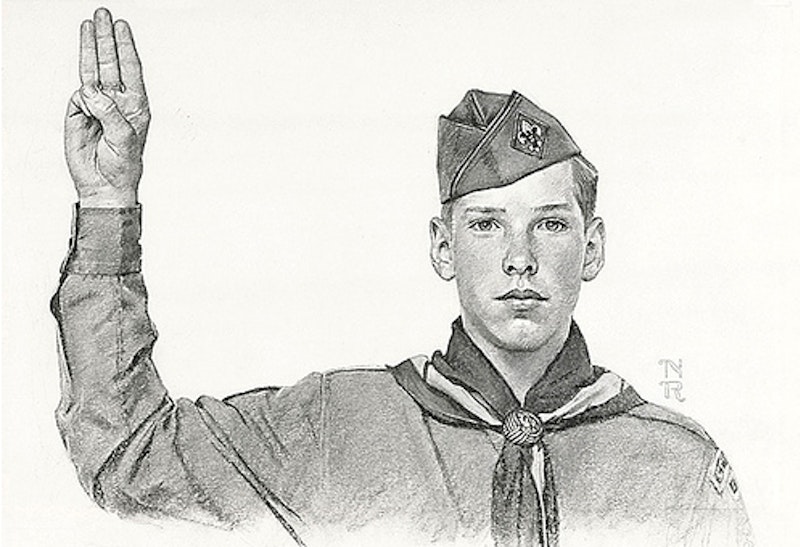

It was Christmas afternoon when, on the way to a matinee of the excellent Up in the Air, I noticed for a low-profile billboard on a turnpike in midtown Baltimore that was a recruitment advertisement for the Boy Scouts of America (BSA). It didn’t surprise me one bit that the illustration was a period piece—very Boy’s Life or Saturday Evening Post—since you almost never hear about the once-iconic organization these days unless there’s some absurd “moral values” controversy over an upstanding, law-abiding BSA scoutmaster hounded by townsfolk when his homosexuality is revealed. I’m not going to wade into that quicksand—not worth the time—but for a few moments in the station wagon last Friday while my wife and sons were bantering about Afghanistan and new Burger King offerings, I was lost in time, transported back to the Long Island of four decades ago, back to my childhood’s Huntington’s Troop 12.

Perhaps it’s peculiar to the East Coast, but the BSA is nearly invisible today; in fact, I don’t know a single person under the age of 40 who was a member of the Scouts. Many years ago, in Manhattan, when my sons were of Cub Scout-age, I sheepishly asked each of them if they wanted to join, and was met with raised eyebrows that suggested their dad was intolerably out of touch. And maybe touched in the head as well. I really had no expectations that they’d have any interest in scouting, but for some reason felt obliged to make the query, if only because all four of their uncles and I spent years, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, under the supervision of Wilson Mott, Troop 12’s scoutmaster.

When I joined the Boy Scouts in 1966 as a Tenderfoot, Mr. Mott was nearly ready to retire, but was still an imposing and exceedingly earnest Gary Cooper sort of man. I have no idea what his age was when he taught about 25 of us how to chop wood at summer camp in Gloversville, New York—given a kid’s perspective on adults, he looked about 70, but was likely at least 15 years younger—but he was all business during the day, only lightening up during evening campfires when on occasion he’d spin an amazing yarn about a harrowing hiking adventure in his past or the hardships of the Great Depression. Maybe, in retrospect, he’d taken a few nips from a flask to loosen up after a long day of corralling sometimes unruly youths, but that never occurred to me at the time.

As the youngest of five boys, there was never any question that I’d follow family tradition and become a member of Troop 12. My mom, who did her time as Cub Scout den mother in the 50s, emphasized to me that excelling as a Scout was a vital extracurricular activity for college applications, even more important than joining the local Key Club (I put my foot down on that one, which distressed her greatly). And though I’d become ambivalent about the entire experience by the time I was 14—in 1969, being a Boy Scout was not exactly something you’d brag about if you ran in the hippie crowd—there’s no doubt it was a worthwhile activity.

Some of what I learned during those years still sticks today, like tying slip, square, bowline, overhand and timber hitch knots, the ability to identify any number of trees and plants, and rudimentary first aid skills. On the other hand, after innumerable 15-mile hikes, building fires and setting up tents for overnight trips, I’ve had my fill of camping. A couple of my brothers still enjoy a trip into the wilderness—although with suitably luxurious accommodations—but not me: I like cities and hotels with all the modern amenities, and generally leave the great outdoors to those of a more adventurous sort.

In fact, it could be all that hiking and tripping over rocks on steep hills filled my lifetime “nature” requirement; I get nervous today when there’s no taxicab within five miles. My friend Chris Styles is quite the opposite: as it happens, he’s currently on a long camping trip in North Carolina, a respite from his successful tech business that he undertakes several times a year. I joke with him about shooting a bear for dinner, kind of like Davy Crockett or Daniel Boone, and, sure enough it turns out that Chris, who’s around 30, was never a Boy Scout.

As for my colleague and buddy Zach Kaufmann, he doesn’t even like baseball—which to me is incompatible with his love and extraordinary knowledge of American folk music—so there was never any question that he’d come up blank if asked to recite the Scout’s Oath. Which I remember to this day: “On my honor, I will do my best / To do my duty to God and my country / To obey the Scout Law / To help other people at all times / To keep myself physically strong, mentally awake and morally straight.”

Okay, it’s kind of hokey—what 14-year-old boy wants to be “morally straight,” since that precludes so many perfectly normal flights of imagination and mischief—but that’s how we opened each weekly meeting on Wednesday nights, led by an Eagle Scout. At my time in Troop 12, that fellow was a total prick—and since he couldn’t swim, which was a required merit badge for attaining Eagle status, a rare distinction, I never trusted the guy, assuming he bribed someone to crawl his way to the top.

Additionally, I was continually at loggerheads with Ronnie, who didn’t appreciate my violating regulations by wearing a psychedelic neckerchief instead of the standard issue red Troop 12 number, and he dismissed me from a meeting one spring day in 1968 for the sin of attaching a Gene McCarthy for President campaign button to my shirt collar.

The following year I laid out my exit strategy from the Scouts, which wasn’t an easy task given my family’s history with Troop 12. Problem was, I hadn’t been too ambitious in gathering the necessary merit badges to move up from my pedestrian First Class rank—by contrast, one of my brothers was an Eagle Scout, and two others made Life—and there was no way my parents would agree to my departure without at least snaring the mid-level Star rank. So I crammed and in two months did the tedious work to gather merit badges for forestry, art, archery, cooking, bugling, stamp collecting, public speaking, scholarship and several more that I can’t remember.

I won’t forget my final day as a Boy Scout. A May ’69 weekend camping excursion was on the docket, and as I had much more pressing, and fun, plans, this was simply out of the question. Talked to my dad, told him I’d call Mr. Mott and bow out gracefully, coming up with some excuse. My father said nothing doing, pal: you’ll go tell Mr. Mott in person and not take the easy way out. So I did, and the aging Scoutmaster was a bit disgusted, especially upon hearing my fib that I’d be present for the next trip. “Rusty, you and I both know you won’t, so let’s just be honest with each other.”

He was right, naturally, and that lesson in character, as my Scouting career mercifully ended, was so plain and direct and true that it still resonates today, 40 years later.