Yesterday I finished up 30 years of parenting (two daughters, a son, and two stepsons), as my youngest daughter Jane headed off to college. About half of that was spent living with my kids’ moms, in situations that were nuclear in more ways than one. And half was spent living alone and being a weekend father.

The literature of weekend parenting, or the male side of joint custody, much less its end, is thin compared to writings about mothering, empty nests, and menopause. I suggest that the fundamental driver of this phenomenon is that women want to read about stuff like that and men don’t, so you just can’t sell your deep explorations of paunch, pattern baldness, child support, prostate issues, and aging divorced daddyhood. But, if you’re paying, I’m playing. If not, I’m giving you 900 words anyway. If you’re a guy, it’s okay to stop reading right here. Warning: there will be feelings.

Let me give you an evaluation of myself as a father. Minute by minute, I’m great with kids. I love to play, physically or verbally or in any other dimension. I enjoy almost everything about close childcare almost all the time, including the cooking and cleaning around it. I have a rare quality of attention, and I tried to lavish it on them, and created some pretty stimulating contexts. Sometimes people, seeing that, have said that I’m a great dad. But I’m not. The first, the actual job of parenting is to be there every day, and to know your children and be known by your children in a way that’s only possible when you do. As my father did with me, I failed by this fundamental standard. For much of their childhoods, I lived somewhere else.

This is an experience common to many dads I’ve known over the years. For one reason or another, we can’t live with Mom anymore: maybe it’s her fault, maybe it’s our fault, probably both. Now, alone (or I suppose with a new partner, though I never moved straight into the next relationship like that), you’re going to try to simulate the situation you helped destroy. You’re going to try to make a semblance of the old family or the old home. You’re secretly consumed by the idea that you’re losing your children, and that you’re damaging them. You’re desperately trying to create a situation that they’ll want to come to and hang around in. You’re trying to keep them from crying for their mother; implicitly, you’re in a competition as to where those kids would rather be, and you’re probably losing. You’re consumed by guilt, as well perhaps by feelings of incompetence. You’re trying to pretend things are alright, and trying to show your children that you haven’t stopped loving them and that nothing is their fault.

That can make for a stilted and forced environment. You try to make real rooms for them, but their real real rooms with their real current stuff are at mommy’s. You try to find friends for them near you, but their real friends are in mommy’s neighborhood. You’re sad, and angry, and confused, and perhaps semi-competent at some traditionally-female parenting skills. In short, you’re a mess. But the point is to keep smiling and keep going. You and your kids end up sort of playing house and, if you’re lucky, trying to make each other feel okay about the whole thing. Even if we rarely write memoirs about this, it’s fucking hard.

But weekend parenting offers certain advantages. I know what life was like for the two moms of my kids after our splits: trying to juggle work, childcare, and perhaps dating, as well as many other things. In general, I had my kids every weekend. And in general, I didn’t try to do anything for those 24 or 48 hours but be with my children: watch their TV shows, play their games, read their books, dance crazy to Cajun music, go on nature walks, put waffles in the toaster oven. I realize that having this time was a luxury, and many dads can’t afford that or don’t have the sorts of careers that allow it, but I could work it around my day job.

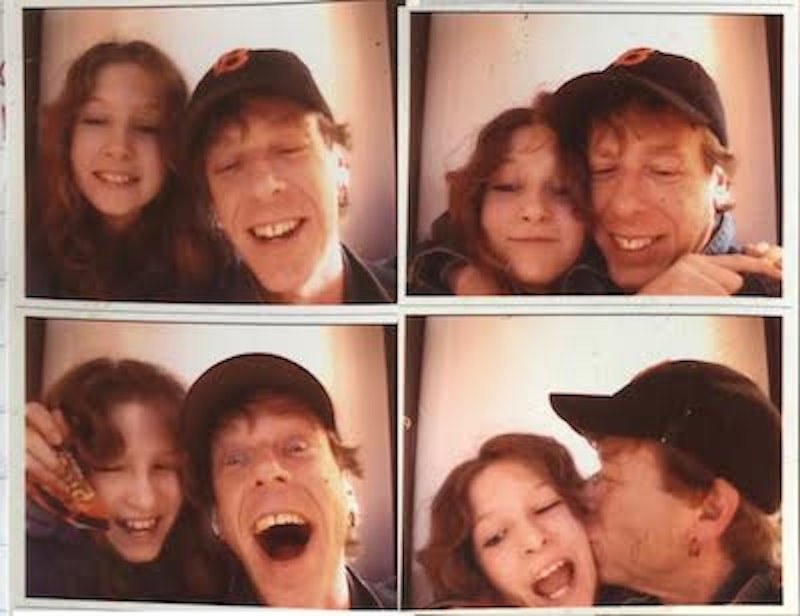

The casual intensity with which I tried to pursue weekend parenting was, again, partly a compensation and a popularity contest: trying to make a place and an atmosphere that could compete with Mom’s, trying to show that my love never paused even if my parenting did, working out feelings of guilt as well as commitment and the resolution to demonstrate this commitment. But it wasn’t just that: it was how I wanted to live and how I wanted to be with kids, and I had many of the most effortlessly happy days of my life in this context, days where I enjoyed myself and my kids, and they enjoyed themselves, and we loved where we were and what we were doing right then.

I think, in other words, that part of what was lost in the everyday work was compensated by the intensity of intermittent parenting. Still, I wish so much that I had been there so much more, and I’ve got so many emotions going this morning—start with joy and self-loathing and pride and terrible sadness—that I can’t really tell which is which or why. Whatever sort of dadding I did, I already miss it “something fierce” as my own (divorced) father used to put it.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell