Excerpted from a recent telephone conversation:

Me: Hey dude. Where do you want to go for lunch?

Friend: I dunno, where do you wanna go?

Me: What are you up to?

Friend: Nothing. You?

Me: Nothing. So, where do you want to go?

Friend: I don't know. You decide.

New Year's is my least favorite holiday. It's not that I hate being hungover from champagne, which I do; not just because I'd rather go without that awful buzzing sound from those paper things you blow into because I would (go without them, that is) and it's not because I'm one of those ad busters, always pointing out when a certain holiday is just a marketing scheme shoved down our throats by some greeting card company. No, I hate New Year's Eve for some other reason. I don't think it's a moral one; it isn't all the hedonism and gluttony. It's something different entirely; it's what the occasion brings out in us. By us I mean my friends—upper-middle class to upper-class white urban college-educated males and females.

None of these people ever plan for New Year's—ever. Here's how it goes down: My friends get together early in the evening to have dinner in small groups at someone's house; then, the entirety of said dinner consists of speculation on which of the possible parties that evening will make the best possible spectacle (the most people, the loudest music, the most chance of disturbances, fights, police, etc); then, the closer it gets to midnight, the smart phones come out and people start texting and calling other friends that have already arrived at one of the locations to collect reconnaissance on the particular scene at that location; bets are hedged and when a certain location reaches its critical mass, this group of friends will drop everything and converge.

The caveat is that this lightning-fast move to a party has grown later and later every year, sometimes not until after the ball has already dropped. It used to be that we could hedge our bets way earlier, and everyone would pretty much know a day ahead of time where the locus was going to be for the passing of that particular year. But as speculation and action grew more and more last-minute, I got kind of sick of calling someone at 11:30 and asking them where they were going and getting the terse "don't know yet," and now I try really really hard not to go anywhere on New Year's. This type of indecision on this particular holiday is a paradigm of what I think will show to be our greatest affliction right up there next to hearing loss. (If you're a prospector on future health problems, I would get into the hearing-aid business ASAP, because when my generation starts to get old, you'd be rich as Daniel Plainview if you figured out some way to provide for a generation that was practically born with ear buds.) Okay. So why do I think that this weird insta-choice, or indecision, or anti-choice, is the greatest social affliction and why do I think that it's peculiar to my generation?

First, I think it's a symptom of an overexposure to narratives. By narrative, I mean anything from a novel to a film. From the way in which a tweet or a text message or a Facebook wall post infers a background story, to the way that something as simple as a headline tells a story. I don't mean so much the order of contingent events that leads to others, but rather the myriad ways in which they are told, consequently implying the ways in which events are seen.

The formulation goes like this: We are not only aware of the infinite number of events that take place in the world everyday but also the infinite number of ways that those events are perceived; growing up, we were taught to make the best possible choice from our options, to weigh the pros and cons, etc. If our options are limitless, the best possible choice does not exist, rendering the methodology we were brought up with useless. The fracture is literally compounded; not only do we perceive the realm of choice as restricted to the realm of actions (the order of events in a story) but also the amount of ways that an event can be seen and told. Because we've seen literally thousands of films, and read thousands of books and newspaper articles, because we've gotten and made so many phone calls and watched so many crappy sitcoms, we are genuinely and acutely aware of the infinite ways that there are on this planet to live our lives, and to see the world and to make choices (see "jam" interlude below) and we've been more aware of this than any generation that has come before us.

They say that there is a certain violence inherent in theater because any one choice that an actor makes is the death of all other choices that the actor could have made in that moment. While I believe that human beings have always been conscious of this idea, I think that my generation's awareness of this fact is acute and completely crippling, and that it is the root cause of all other inexplicable affliction you see going on with young people.

Almost 60 years ago, Jean Paul Sartre wrote that when one human being does something, they are effectively giving permission to all other human beings to do that thing (he was trying to devise an ethic without a God) but I disagree, or I think that Sartre has since been proven wrong. Giving humanity permission to essentially do everything (a reach for the moon and you'll fall among the stars-type mentality) is a latent command of our society. It is the command to try new things. It is the command to seek out as many experiences as possible. It is the command to eat the oyster that they say is a world. Our eyes are bigger than our stomachs. It is the command that we quite literally do everything because everything can be done and it is, of course, an impossible demand; a demand that confuses the ability of the totality of the human race with the relatively limited realm of personal and particular ability. So we think that our capacity for choice is greater than we are actually built for. Surely, the human brain has been wired with a distaste for an excess of options for a long, long time, but surely too our ancestors didn't have so many New Year's parties, or potential dates, or even books or newspapers from which to choose.

Dostoevsky wrote that if God is dead, then everything is permissible. What my generation has shown (and God is truly dead for my generation) is that if God is dead, nothing is permissible, that when we're confronted with the sheer multitude of narratives possible in our own lives, we imagine ourselves wildly untethered and lost, spinning on this ball through this great big we-don't-know-what and for fear, we throw our trembling selves closer to the spinning earth.

You know what I'm talking about. Chances are you've felt it while driving on some remote highway somewhere and you have the liberating and also terrifying thought that no one knows where you are and this makes everything that you do seem incredibly important or completely vain and not important at all. I get it a lot. Sometimes, in college, driving back from a holiday through the mountains late at night I would get this feeling and have to pull over and sit on the ground for a while next to my car because I was convinced in this weird way that gravity might suddenly reverse itself or disappear altogether and I'd be flung out into the huge black sky over New York state.

A study was performed at Columbia in which a group of people were given a small number of jams to sample and then buy their favorite one. In general, the subjects had no problem identifying and purchasing their favorite jam. Then, a different group of people were asked to do the same thing, but to choose from a wider selection of jams. Chaos ensued. The subjects were unable to decide which they liked most and almost all of them were unhappy with their final decision, second guessing themselves or refusing outright to buy any of the multitude of jams they had to chose from.

Abulia (n.) is defined by the American Heritage Dictionary as "the loss or impairment of the ability to make decisions or act independently," and if one suffers from this condition one is said to be "abulic," which comes from New Latin, without will, indecision.

I would like to announce the candidacy of this term to be included in the forthcoming edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and to declare that we are a nation of the abulic, and as such living not in a state called "America," but in a state called "Abulia." The United States of Abulia. USA. Instead of standing with our hats off and our hands over our hearts when the National Anthem is played, we should all just curl up on the floor in the fetal position, because in this our current state of Abulia, this would be the truest physical gesture of patriotism.

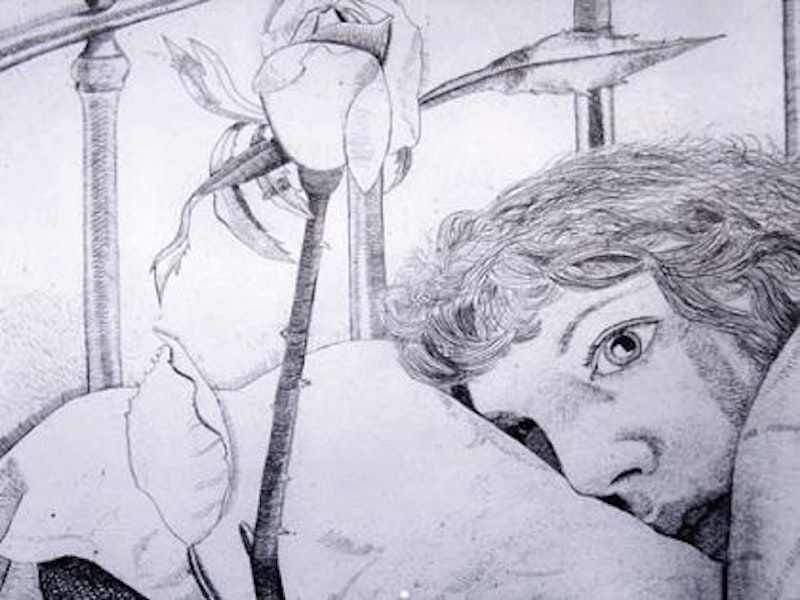

I can remember a time when I was so depressed that making any decision took hours. Once, I had been sick with a bad cold and stayed in bed for about 20 hours. When I finally got up, I was desperately hungry, starving in fact, but there was nothing in my house to eat. So the question presented itself of where to get food. I live in a city, so my choices were countless, but I could not come to a conclusion, for fear, I think, that while I was eating one thing, I would be sitting with the unbearble knowledge that my choice to eat that one thing had strangled the possibility of eating some other thing, which may have been more satisfying. Hold out, I told myself, and choose the best option. I think I sat there in a kind of daze for 10 hours, by the end of which I bought McDonald's or Dominos or something horrible like that because I perceived such a decision to be the opposite of having to make any real decision. The anti-choice, if you will.

Abulia is amplified by depression, or depression is amplified by abulia, I'm not sure which came first. But I'm pretty sure that it was the loss of the ability to act independently. Studies [http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=101334645] have linked dopamine levels in the brain to how fast and how confidently we can make decisions. In turn, I don't really see it as odd that an excess of dopamine often leads people to gambling problems, which, in a way, is actually an obsession with making choices, albeit arbitrary ones, over and over again. As a nation that seems to be getting more and more depressed (our insatiable appetite for prescription and illegal narcotics are evidence of this), it's going to have more difficulty deciding really important issues. I couldn't decide where to get lunch; what if it was, god forbid, a healthcare package? A war? Who to marry? Whether or not to have kids? On the other hand, there is a fetishism of risk and choice which approaches recklessness—"I'm the decider"—and both poles look pretty, and unavoidably, bleak.

Start looking around and abulia is everywhere in our culture.

In our cinema, I'm reminded of Garden State, which I think is largely a film about a guy who can't make decisions, and finds relief for his abulia in moments of temporal originality or authenticity. Those scenes when Zach Braff is screaming at the sky and these are somehow choices/authentic acts because no one is doing that particular thing in that particular space and instant in time, which, if that's supposed to be the only ethic left, or the ethic of my generation, is really really sad. So-called Mumblecore cinema (recent independent American films that emphasize the use of non-professional actors, natural lighting and meandering narrative lines like Hannah Takes the Stairs, Kissing on the Mouth, Funny Ha Ha, Greenberg) is another example of films that are about the difficulty of making decisions and in turn, is itself a cinema that does not make decisions. Run Lola Run and films with multiple contingency plot lines are a good example; chose your own adventure! It's in our music (I'm lost in the supermarket, I can no longer shop happily, again, see "jam" interlude), both in content and in the ecology of how it's listened to; go to any party with an iPod or a Mac and playlist and notice how no one will listen to a track all the way through before switching to the next. I used to suffer these terrible episodes when I'd go to a video store where I knew exactly what I wanted to rent before I walked in the door and once inside and confronted with all my options, I would promptly forget and end up leaving with some piece of crap. It's the same at bookstores. It's even the same on Netflix or Amazon, which, according to their long-tail business model, was supposed to alleviate those choice-overloads and have only ended up making them worse: now, with everything at my fingertips, I literally can't choose.

It's the same for romantic relationships. I'm nostalgic for a time I never lived through, if such a time ever actually existed, where'd you lived in some small town and had maybe four suitable spouses and it was just a matter of time before you chose one among those four. I'm going to admit something here, I'm a member of this dating website. It's free. It's called OK Cupid, and, alright, imagine if you had the same experience at the video store except in a room full of women but, except, the room full of women is on the Internet and infinitely large and full. Don't get me wrong, it's a great site and well developed but I can't help but think that it's just exacerbating a problem that it itself set out to mollify—that is, alienation, because of our inability to make decisions (I think that because of technology, people are really, really sad because it's harder for them to make decisions and okcupid is trying to solve a problem through the very medium causing it).

It's the same for jobs and careers. We hold out and we sell ourselves short and we wait for the best possible New Year's Eve party and the best possible never comes. I'm the worst, by the way, of the people I know with abulia and I end up going out on no dates with any girl because I'm plagued with the thought that if I go out with one girl then I will have ruined the chance I had to go out with any other girl on that particular evening and I fear that for this reason I will spend the rest of my life alone.

As you can probably imagine I'm having a difficult time deciding how to end this essay. Case in point: Joan Didion wrote that we tell ourselves stories in order to live. While we do create ourselves backwards (even Freud recognized that trauma wasn't created in medias res but much later, once the victim had told themselves the story of what happened to them) I think that we tell ourselves an excess of stories in order to die, because the desire to make no choice at all has become so strong, which is really a desire for death, in which case we have a very severe public health problem on our hands, here in Abulia.

By far the strangest quality of any narrative is it's ending; a kind of vacuum, an ending makes everything that came before that final act to seem somehow in the service of the ending (this thing led to this thing which led to this thing) and makes our lives seem retroactive and already-lived. Distrust the finality of endings because nothing ever really ends. Seasoned professionals of any trade will often tell a story about a contingency that led their career in some direction or other ("So there I was, in a hallway, when who should walk out of the office but....") and they tell these stories with a measure of confidence, to make you believe that they always planned on being in that random place at that random time when really they were just as uncertain, and their lives turned out just as tragic for those missed choices and decisions unmade, as anyone's.

Such certainty should be distrusted. As many choices as our generation has, or think we have, very few of us can deal well with boredom or being alone and I'm tempted to venture the possible solution of getting acquainted with boredom and loneliness and one way of doing this is to convince yourself that the command of society to do and choose and to move is also the command of late capitalism and, as such, is a corrupt command and not in your best interest. Go to the non-New Year's party of Abulia instead, curl up on the floor in the fetal position with everyone else and drink a glass of champagne and think about who you want to kiss and then kiss all of them. Walk around in Abulia. Get to know it. Keep exploring. Try not to take it too seriously.