Superstition has a way of ingraining itself into the fabric of our societies. If you don’t accept the notion or you’re embarrassed admitting it, most have at least one obsessive anxiety. Many of these unreasonable phobias have persisted for centuries. The majority don’t pose a threat. Others are incomprehensible.

Ask a numerologist and they’ll tell you 13 is a vehemently disliked number, especially when it falls on a Friday. Still to this day, the jinx of Friday the 13th is responsible for an estimated 800 to 900 million dollars in business losses.

Does 13 really bring bad luck? Here’s a case of an anomaly with a long history of too many coincidences. To put triskaidekaphobia (13 phobia) in perspective; we step on a few cracks, walk under ladders and shatter some mirrors—proceed with caution. The number’s early origins can be traced back to Mesopotamia (4500 to 1900 BC.) The Sumerians developed one of the earliest counting systems: mathematics. Twelve functioned as an idea of completion: a dozen eggs or 12 months to the year. That left 13 out in the cold.

Around 2300 B.C., the Babylonians etched a four-ton slab of diorite called the Code of Hammurabi. Voilà, their message of judicial justice established rules on how to deal with misconduct in society. However, the 13th law was accidentally left off the code due to an error. A closer look reveals the piece of rock doesn’t list items numerically. On a grim note, several of the 282 laws called for a violator’s tongue, arm or hand amputated as a penalty.

Like many religions, faith continues to play an important role in forming superstition. Myth and tales come natural to our true being. Going back to the prehistoric “sitting around the fire” hunter-gatherer, tribal structure of human civilization, we told stories. In many cases, our daily “religious” rituals and beliefs are rooted in these traditions.

In Christianity, Judas was the 13th guest at The Last Supper, which took place the night before Jesus’ crucifixion on Good Friday. Every year around Easter a non-Christian co-worker would say to me, “I don’t get why you guys call it good?”

Norse mythology portrays Loki as a god known for changing shape and sex. The unliked thirteenth guest trickster caused chaos by crashing a Valhalla party of twelve. He instigated having another god Balder murdered by mistletoe. Then the Earth went dark. Loki must have a great talent agent because he’s also a Marvel superhero.

Conjure up a picture of the complex Middle Ages (500 to 1500), a world of aristocrats, peasants and castles during the Crusades. The Knights Templar were a paramilitary and financial organization hired by the Church to protect Holy Land pilgrims from bandits. For two centuries throughout Europe and elsewhere in the world, the Knights gained vast power, wealth and influence.

As dawn broke on October 13, 1307, a drama unfolded. Charges of heresy and other improper accusations arose. The efforts a greedy, jealous king, not the Pope made the call. King Philip VI of France ordered the Knights Templar execution. No killings occurred on that day, but members were imprisoned and tortured for confessions.

Jumping centuries ahead, looking back at the 1880s, Civil War vet Captain William Fowler was one of the more vivacious New York City personalities of the day. Fowler created a regular, private social gathering called the Thirteen Club. At one point, there were over 300 members. It took a year to find enough disciples to join a club that thumbed its nose at the afflicted number.

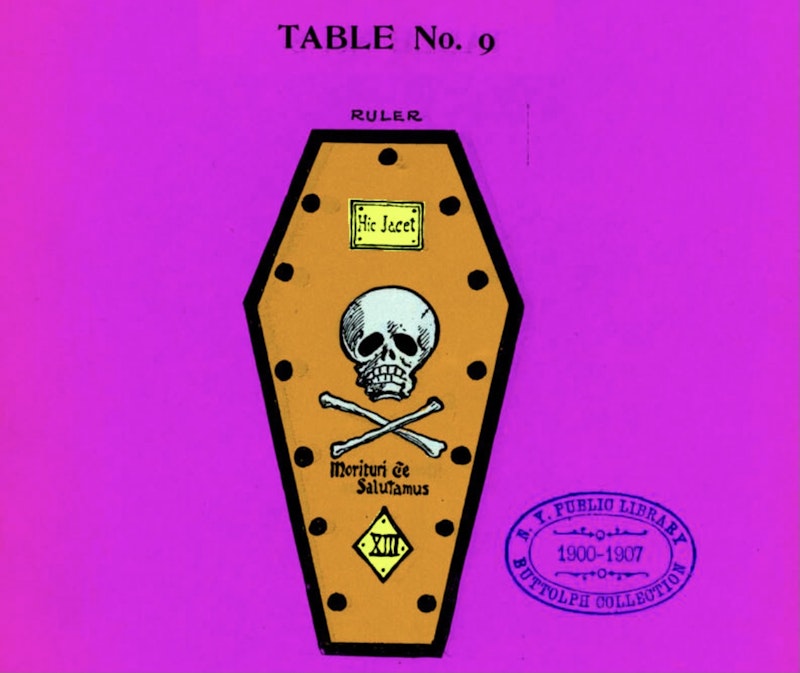

Fowler bought a pub. The Knickerbocker Cottage was then located at 454 6th Ave. and 28th St. According to The New York Historical Society: 8:13 pm, Friday, January 13, 1882, “…under a banner that read ‘Morituri te Salutamus’ or ‘Those of us who are about to die salute you.’ Thirteentables and candles readied the first of thirteen courses: big platters of lobster salad molded into a coffin shape.” It was common practice for men and women to join these kind of eccentric dining clubs in the late-19th century.

When movies were still silent, Friday, the Thirteenth was published by controversial writer Thomas Lawson in 1907. The plot revolved around the dubious financial dealings of a stockbroker’s plans to bring down Wall Street on Friday the 13th. The book, considered panic fiction, set a tone for the mystical number’s 20th-century presence. “…Friday, the 13th of November, drifted over Manhattan Island in a drear drizzle of marrow-chilling haze, which just missed being rain—one of those New York days that give a hesitating suicide renewed courage.”

Who’d have guessed that 85 percent of elevator panels don’t have a symbol for the 13th floor, and that this could be the inspiration for a band name? Roky Erickson, the vocalist for the tripped-out 13th Floor Elevators. Like many artists of the day, extra-strong doses of hallucinogenic substances held a certain appeal.

The 13th Floor Elevators’ jangly guitar, electric jug, feral vocals and frantic harmonica formed an exquisite garage rock masterpiece: the 1966 hit You’re Gonna Miss Me. Trivia buffs, it’s a cover of an earlier 1965 super-raw single by Roky’s first band The Spades. The Texas musician suffered with lifelong schizophrenia. In his Rolling Stone obituary: Roky was arrested in 1969 for a single joint and put away until 1972 where “he was essentially tortured by electroconvulsive therapy and Thorazine treatments.” After a brief comeback in the early-2000s, Roky “Oh, you’re gonna miss me, baby” Erickson took his final trip at age 71 in 2019.

Thirteen was lucky in 1980. The release of Friday the 13th marked the beginning of a successful, horror movie genre. There are 12 slasher films, as well as a television series, novels, comics, books, and other merchandise. The bloodwork focuses on a maniacal, hockey-mask wearing, serial killer: Jason Voorhees, However, in the first film, his mom does all the killing. “They were warned… they are doomed” a group of teens are stalked and murdered at Camp Crystal Lake. Once the body count gets started, it lasts for quite a while.

As the 13 continues to surmise impending doom, whether genuine or imagined, we move forward knowing people will continue to avoid engaging in any activity that makes them feel uneasy. Meanwhile, we’ll have to wait around until May 2022 to see if a misinterpreted date, really is unlucky.