An article in The Economist headlined “The Craze for Teaching Chinese May Be a Misguided Fad” inspired debate amongst all kinds of people, showing up everywhere from Omniglot to a Chinese law blog. The debate has two basic camps: those who think everyone in the world speaks English, and those who believe China’s about to hit its peak and become the next superpower. With the Internet allowing cross-cultural communication on one hand, and blue-shirted men trying to plant Best Buy franchises all over the world on the other, people are slowly but surely getting nervous that there is not yet a lingua franca to fall back on. But before weighing in on the English/Chinese debate, I have to ask a question. Whatever happened to Esperanto?

I think I first heard of Esperanto as a joke, probably on Saturday Night Live or a similar show. When I saw it on the sidebar of Wikipedia, right between “English” and “Español,” I realized it was a real language. I’m assuming that most people reading this have about as much education on Esperanto as I did right then, so here’s some background. It was created by a man named L. L. Zamenhof, and has about 1000 native speakers. Esperanto-advocating websites claim it to be designed for ease of learning by everyone in the world. It uses the Roman alphabet with various accents, and features conjugations most similar to Spanish. The name is close to the Spanish word for “hoping,” which is “esperando.”

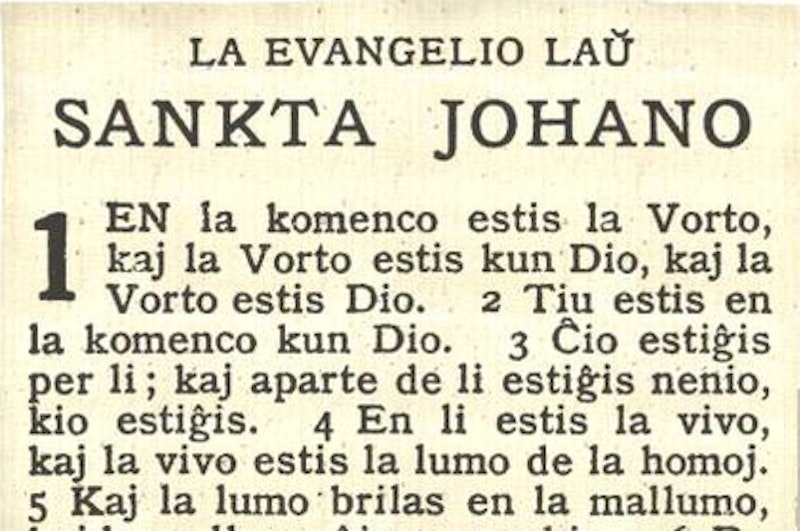

It looks like Spanish, but with a lot of clumsy k’s mixed in. (I’m not a big fan of the letter K, probably from seeing it tackily replacing c’s for my whole life. Krispy Kreme, etc.) It is obviously influenced by Roman languages, and from the small amount of Russian that I had to learn to get through A Clockwork Orange, there were some Eastern European elements.

After reading enough background to figure out the basic structure, I can’t see how it would be easier than Spanish itself. You may not know it from being bored during high school Spanish class, but it is one of the simplest, clearest languages possible. Every letter is always pronounced the same (with the exception of g and c, and some regional differences). Verb conjugations are constant and methodical. The pronunciation is relatively staccato, meaning the beginning and ending of words are easy to hear and clearly emphasized, unlike French and Portuguese. I won’t bore you with any more details, but it seems unnecessary to create a derivation of Spanish that isn’t apparently simpler and isn’t already spoken by about 400 million people.

I’m also skeptical about how much enthusiasm the collective speakers of the world can whip up for a language that has no real history. Esperanto was created in the 1880s, and hasn’t nodded its head far into any culture. Knowing that a language was the medium for the works of greats like Dante, Freud, or Jean Paul Sartre has probably been the impetus for thousands of people to choose one over the other in school.

So am I implying that Spanish be the lingua franca? Not necessarily. Many languages would be simpler to teach than both English and Chinese. Korean, for example, has a painstakingly designed phonetic system of syllables written to look like the shape of the mouth when speaking them. It is said that most people of any language can learn the Korean writing system in about three hours. Catalan, spoken in Spain, is a blend of Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and French (that is a somewhat crude definition of Catalan, but not incorrect) that would be simple for anyone with a background in Romance languages to learn. But ultimately, I realize that the language that will catch on the most is the one belonging to the most culturally domineering nation.

It’s possible that Chinese could surpass English as a lingua franca. The argument that English is easier than Chinese is probably only true to those who already speak English. Sure Chinese uses four different tones (I am referring to Mandarin, not Cantonese, which has more) and uses an ideographic writing system, but the tones make Chinese very musical, and thus its phrases are easier to memorize. I’ve studied both Chinese and Japanese, and discovered that ideograms are much easier to read than foreign alphabets. I could never just look at a Japanese word and know what it meant without reading through it, but all Chinese words read that way, because their meaning is hinted at by the elements of the character. English, on the other hand, has such inconsistent spelling that some linguists have called it partially ideographic as well, meaning that a word is learned by memorizing how it looks, not necessarily how it’s read or pronounced. (Like “laughter.”) Verb conjugations use systems from many different linguistic backgrounds, and are hard to predict without routine memorization. (Eat/ate, love/loved.)

So how likely is it that your future children are going to be hyped-up to learn Chinese? Despite all the linguistic jargon I’ve shoved at you, money is probably the best indicator. Nobody in my high school Spanish class really learned much Spanish. When we learned the Spanish equivalent of I/Me, “Yo/Me,” everyone grabbed onto the familiar word “me” and ditched “Yo” for the rest of the term. (From then on, everyone was saying things like, “me ate cereal for breakfast.”) It’s not that they were dim, they just couldn’t foresee knowing Spanish as benefitting them in the future, and didn’t want to exert mental energy to do so. Kids in my Chinese class are a different story. Let’s just say most are business majors, and they don’t mind hollowing out a bit of space in their long-term memories to fit in some phrases that could add another zero to their future income.

Sorry, Esperanto, unless a territory of native speakers finds a gold mine, I doubt people will be saying “kiel vi fartas” (their unfortunate phrase for “how are you doing?”) to you.

Universal and Invisible

Whatever happened to Esperanto?

The Bible in Esperanto. Copyright World Scriptures.