It’s almost two in the morning, and I’m awake thinking about the patriarch Lot. If you’re not familiar with Chapters 11 through 14 of Genesis—“page turners, they [are] not,” as Yoda might say—then you probably don’t remember this guy. I mean, he’s just sort of there, traveling with Abram (later, “Abraham”) and the rest of the family. Then, in what amounts to his first big scene, Lot makes the terrible decision to lead some of his people toward a green Jordanian plain, where they can cease roaming and settle down:

And Lot raised his eyes and saw the whole plain of the Jordan, saw that all of it was well-watered, before the LORD’s destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, like the garden of the LORD, like the land of Egypt, till you come to Zoar. And Lot chose for himself the whole plain of the Jordan, and Lot journeyed eastward, and they parted from one another. Abram dwelled in the land of Canaan and Lot dwelled in the cities of the plain, and he set up his tent near Sodom.

This isn’t where any of the Israelites are supposed to drop anchor, incidentally; as Abram is fully aware, they’re supposed to go to Canaan. Abram does go there and receives God’s blessing. Lot, however, can’t see past the beauty and fertility of decadent Jordan, where people are living on the edge of a knife. (“Lot” means “veil” in Hebrew; Lot is the archetypal deluded homesteader, unable to see past the veils of appearance in the strange land he’s chosen.) Soon after, God sends angels to Sodom and Gomorrah to confirm that both cities ought to be destroyed. The angels are supposed to keep an eye out for good people, in order to warn them of what’s coming. Lot bumps into them. Though he’s characteristically blind to their true nature, he does the right thing, offering them hospitality. Unfortunately, other Sodomites have seen the newcomers as well. That evening, a mob forms, full of people lusting to give these strangers a very different “welcome”:

They had not yet lain down when the men of the city, the men of Sodom, drew round the house, from lads to elders, every last man of them. And they called out to Lot and said, “Where are the men who came to you tonight? Bring them out to us so that we may know them!” And Lot went out to them at the entrance, closing the door behind him, and he said, “Please, my brothers, do no harm.” (Gen. 19)

Then Lot has another great idea. He’ll appease the mob by letting them rape his virgin daughters! That ought to calm them down! But such terrorists do not negotiate:

“Look, I have two daughters who have known no man. Let me bring them out to you and do to them whatever you want. Only to these men do nothing, for have they not come under the shadow of my roof-beam?” And they said, “Step aside.” And they said, “This person came as a sojourner and he sets himself up to judge!”

By the merciless logic of the Tanakh, this is actually the right thing to do; the messengers of God weigh heavier, on the scales of justice, than Lot’s own daughters. The angels, impressed by Lot’s behavior, repay him with a warning: “Who do you still have here?... Whomever you have in the city take out of the place. For we are about to destroy [it].” Lot hesitates. The angels forcibly remove him and his family from Sodom (“in the LORD’s compassion for him”). One tells Lot, “Flee for your life. Don’t look behind you and don’t stop anywhere on the plain.”

Lot eventually strikes a deal with them: if they’ll spare the city of Zoar, he’ll flee. Lot’s wife is a party to all this, but she disobeys God’s instructions. She’s punished for it in one unforgettable sentence: “And his wife looked back and she became a pillar of salt.” With that Lot’s story comes nearly to an end. One more thing occurs. His despairing daughters, living like animals with Lot in a cave near Zoar, get him drunk in order to sleep with him and conceive. Their plan succeeds. Their sons, Moab and Ammon, found two great nations in their turn.

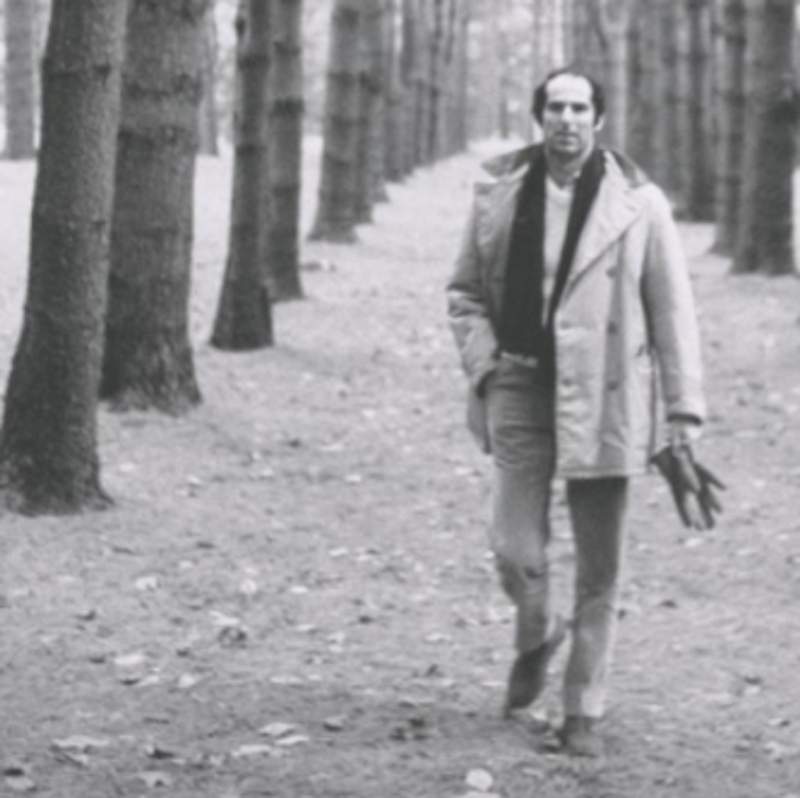

This may strike you as too much information about a Biblical patriarch whom you’d pretty much forgotten, it turns out, for a reason. And you may be right. But it’s still far more compact and sensible than Philip Roth: The Biography, Blake Bailey’s Tolstoyan new epic delivering all the gory, pointless details of one writer’s petty, blinkered life. We don’t remember Philip Roth because he was a good man; likewise, I doubt even the authors of Genesis would have much to say in Lot’s defense. We remember Lot because he is part of an important lineage. We remember Roth because his books have won a place in the history of America, the history of Judaic culture, and ultimately, the story of the world. Like Lot, Roth preferred fertile, blooming fields—carnality and decadence—even if he was doomed to always consider himself an outcast, a “sojourner,” in more permissive milieus. Like Lot, Roth finally chose to flee from the world after dabbling in it. He made his most lasting home in the cave-like seclusion of a New England cabin. He was intoxicated by women, but being his muse was a thankless job. His exes resented him bitterly. Above all, they resented spending so long in second place: Roth was all too willing to sacrifice the real women in his life for his fiction.

Laura Marsh, trashing Bailey’s book in a recent article for The New Republic, tunes Bailey up for all the right reasons. Bailey’s an embarrassing fanboy who likes everything about Roth, including the sound of his idol urinating. Bailey tries out every rhetorical device he thinks Roth would like in an attempt to make Roth’s women seem like impossible bitches. He imitates Roth’s lingo (“a pretty shiksa”). He picks up Roth’s habit of stealing profound thunderclaps from Thomas Wolfe—he describes Roth’s struggles with his first wife as “years of…deepening turbulence.” He even invites his reader to imagine all the “gorgeous young women” tempting Roth into adultery. Marsh understandably sums Bailey up as an “adoring wingman who thinks his friend can do better.”

I don’t have any sympathy for Roth’s mistakes. The best thing about his life—his successful attempt to create a sanctuary where he could write—strikes me as Roth’s attempt to woo eternity at any price. That kind of project appears both nostalgic and ridiculous from our perspective, now that we’re on the brink of (probably catastrophic) planetary change. Eight years ago, in a wild and unpublishable manifesto entitled “An Ark Without A Covenant,” I wrote this about Roth and his quiet little cabin:

Like most would-be writers of my generation, I inherited a complicated and romantic fantasy of what being a writer actually entailed. First, hard living. Next, the manuscript—a work of genius. Then, the submissions to publishing houses, dozens of them. Failure. Ridicule. Then, in the darkest hour—triumph! Appearing in print. Being able to buy my own book at the Barnes & Noble. A legacy. A troubled relationship to bygone writers. A bad second novel. A Great American Novel. Essays. Teaching at a university. Solitude. Writer’s retreats. Even more hard living. “Experimental” novels. Finally, one day, after my death, being an object of fascination for literary critics and college students.

Then, a couple of weeks ago, I heard an interview on Fresh Air with Philip Roth. He’s one of my literary heroes, and in essence, the life I’ve described above is the one he actually lived. Furthermore, Roth, like most 20th Century novelists, actually had a very old-fashioned notion of what literature was supposed to do. It was supposed to tell The Truth. I don’t know where exactly we got this hardscrabble idea of The Truth from—Hemingway, probably—but in a single bound, it explains why people like me have so much trouble writing fantasy or science fiction. Sure, you could bend reality, a little. That’s what Thomas Pynchon does. You could dabble in poetic lyricism, like Henry Miller, and you could try writing in the language of schizophrenia, like Hunter S. Thompson or Denis Johnson. But at the end of the day, an author like Johnson still has more in common with Richard Ford than he does with John of Patmos. He is trying to say something Real and True. And if that doesn’t ENTERTAIN you, guess what? It’s not supposed to.

The problem now, though, is more than just the problems one has proving that this kind of aggressive, Socratic fiction is actually a moral benefit to society under the best of circumstances. At this point, the circumstances are miserably bad. A realist (Ford, for example) has such a miniscule and distracted audience that his impact on society is too small to measure. Furthermore, it is questionable whether realism even is serving a Socratic function anymore—that is, whether it really still has the capacity to provoke people into changing their lives. To be honest, I don’t think it does.

Let’s leave aside, for one moment, the pertinence of realism in our phantasmic, frightening modern world. There’s also the age-old problem with literary celebrity, the one that plagues every Roth-like writer obsessed with The Truth: people want the facts about your life so they can connect the dots in your fiction. (Roth, always an obliging author, called his autobiography The Facts.) Marsh can’t stop herself from doing the same thing: “It was the faked pregnancy that had the longest and most destabilizing effect on Roth’s writing…Eventually Roth would have Maureen Tarnopol in My Life as a Man carry out the same deception that Margaret Martinson had in real life, but his desire for a resounding guilty verdict didn’t fade.”

No. First, Roth published 27 novels and novellas in the course of his life. He did his best work after his failed marriage to Martinson. I’m pretty sure he wasn’t destabilized beyond repair. Second, it’s silly to expect a human being to become karmically aligned and beatifically serene the second they publish a fictional version of a hurt they once suffered for real; scars don’t transfer from the heart to the page like we might wish. Instead, the fictional version is a photocopy—or, perhaps, a clever way to lie. I can tell you what happens to a faked pregnancy when you put it in Maureen Tarnopol’s hands: it becomes a masterpiece. It’s fucking incredible to watch Maureen Tarnopol in action. She’s a perfect diva. For example, here’s the “urine fraud” scene from My Life as a Man:

The morning after Maureen had announced herself pregnant, I told her to take a specimen of urine to the pharmacy on Second and Ninth; that way, said I without hiding my skepticism, we could shortly learn just how pregnant she was. “In other words, you don’t believe me. You want to close your eyes to the whole thing!” “Just take the urine and shut up.” So she did as she was told: took a specimen of urine to the drugstore for the pregnancy test—only it wasn’t her urine. I did not find this out until three years later, when she confessed to me (in the midst of a suicide attempt) that she had gone from my apartment to the drugstore by way of Tompkins Square Park, lately the hippie center of the East Village, but back in the fifties still a place for the neighborhood poor to congregate and take the sun. There she approached a pregnant Negro woman pushing a baby carriage and told her she represented a scientific organization willing to pay the woman for a sample of her urine. Negotiations ensued. Agreement reached, they retired to the hallway of a tenement building on Avenue B to complete the transaction. The pregnant woman pulled her underpants down to her knees, and squatting in a corner of the unsavory hallway—still heaped with rubbish (just as Maureen had described it) when I paid an unsentimental visit to the scene of the crime upon my return to New York only a few years later—delivered forth into Maureen’s preserve jar the stream that sealed my fate. Here Maureen forked over two dollars and twenty-five cents. She drove a hard bargain, my wife.

You have to marvel at it. Maureen’s will-to-power is magnificent. By the time she’s exploiting the pregnant “Negro woman,” in a scene horrifyingly alive with Maureen’s psychotic willingness to cut corners, Roth’s turned the narrative into a split-screen, just so he can fit in her attempted suicide and her attempted deathbed scene from years later. Maureen is a one-woman army who can parrot Roth’s moral language back to him (“You want to close your eyes to the whole thing!”) and then, two seconds later, do a credible impersonation of whoever recruited Henrietta Lacks. You want to know what I thought when I read this novel, for the first time, at the tender age of 21? What a woman, I thought. She wears her malice like it’s mink. When Maureen Tarnopol emerges fully-grown, from Philip Roth’s brain, a terrible beauty is born.

The narrator of this wretched anecdote interests me too, though; Maureen is sharing the spotlight more than she knows. He’s a sweet guy: “Just take the urine and shut up.” He’s got nice, reasonable expectations: “She did as she was told.” He doesn’t see, or doesn’t care, that the woman who sold Maureen her pee probably wasn’t anybody’s fool. He steps gingerly over the sentence he must write about that “unsavory” hallway wherein “the scene of the crime” can be found; he’s picky sometimes, and likes his euphemisms. Of course, he’s also Humphrey Bogart, collecting evidence about the sob story some dame tried to put over on him. There are “specimens,” and “negotiations,” and a “transaction” of dubious merit. “We could shortly learn just how pregnant she was,” he sneers. He’s a peach of a guy, really, when you take his measure. I’m not saying he deserves to be deceived like this. It’s deeper than that. He’s living in a hell of his own making, and he won’t even confess to survivinghis marriage to a criminal. You have to glean, from the way he keeps referring to things that happen “years later,” that when Maureen “sealed his fate” she didn’t do a very good job.

Because Roth puts Maureen near the top of Hell’s pecking order, and pins his narrator beneath such a glaring and merciless light, I don’t find his writing misogynistic. Marsh does, though, as she finally admits:

In life, as in his fiction, Roth seems to have sorted women into distinct groups: those who could help him and work things out for him—the facilitators and curators of Rothworld—and those who dared ask something from him (“half a pound of Parmesan cheese”). The second group does not fare well.

This is a callback to a quote from Hermione Lee, who sorted Roth’s women for him: “overprotective mothers,” “monstrously unmanning wives,” “consoling, tender, sensible girlfriends,” and “recklessly libidinous sexual objects.” This isn’t just wrong; it’s blasphemy! Maureen Tarnopol’s closest relative is some Greek goddess or other, as I’ve already suggested above; she’d probably enjoy hanging out with Juno, or the Gorgons. She’s so much larger-than-life that it’s impossible to resent her for being a ballbuster. The same goes for the rest of Roth’s types. Roth thinks overprotective mothers are basically right about the world, and marvels at their ability to stay one step ahead of its hazards. He thinks consoling, tender, sensible girlfriends are messengers of God. And his recklessly libidinous female prodigies of sex are more liberated than anyone else, male or female, within 1000 miles.

It’s easy to retort that not all women want to be deified, or to point out that starring in a Roth fantasy must be exhausting. That’s true, but it still doesn’t make Roth a misogynist. He puts men on pedestals of his own making too. The homunculus in Operation Shylock, a man who’s also named Philip Roth, is as evil and entertaining as Maureen Tarnopol. The fathers in his novels, while not overprotective, are great engines of ambition. They’re inexhaustible storehouses of prudence, know-how, and tradition, and have the same fixed ideas about children as their wives. In fact, nobody who appears in a Roth novel gets an easy gig; everyone has to justify their existence by carrying on, unceasingly, at the top of their lungs. I didn’t read Roth because he was dirty or smart, though he was both. I read him because he showed me that anger could be gorgeous. Every Roth novel holds out the possibility of loving people you hate in a real, motivating, honest way. That makes hate something we can live with, instead of allowing it to stay a secret and a poison. Remember, most of the people around you won’t admit to hating anyone.Roth is the exception: a hate-filled Jew going door-to-door, undaunted, preaching admiration for your enemies.Telling me Roth couldn’t pull off this same trick in real life isn’t a revelation. Almost nobody can. That’s precisely why it’s compelling to imagine.

Now let me tell you where all this deifying and admiring and elegizing, courtesy of Roth, has its rendezvous with The Truth, and facts, and what’s real. I have my own Roth story. When I was 33, I had a Ph.D. in English and Ethics. My teaching career was already in motion. But I still felt bad enough about myself to come within six inches of suicide after a high school reunion. (I counted the inches from my car’s wheels to the cliff, a 200-foot drop. I came that close to doing a Thelma & Louise.) I was lonely. I was so alone that I’d even organized, on behalf of everyone who disdained me in high school,the very same reunion that made me suicidal when I attended. I’d even found time to be married once, to a version of Maureen Tarnopol. I cried my way through most of that brief marriage—but I have to say, to give credit where it’s due, that the divorce still managed to be worse.

I went to Italy. I fell in love with a woman I met there. She was Canadian, from Winnipeg; she was much younger than me. She was a rising junior at Concordia University, living and working in Montreal. Because she loved me back, I began a relationship with someone who didn’t know the intellectual circles and reference points that I now took for granted. “What do you think of Aaron Sorkin?” I asked her, at one point. “I think,” she said, hesitating, “that I’d like to know more about him.” She never completed her degree; after leaving school, she ended up joining me in New Haven, Connecticut. We got married four months later.

Since she reads everything I write, she’ll read my next quote, from Roth’s novel The Dying Animal. I think it will ring true for her:

She finds culture important in a reverential, old-fashioned way. Not that it’s something she wishes to live by. She doesn’t and she couldn’t—too traditionally well brought up for that—but it’s important and wonderful as nothing else she knows is. She’s the one who finds the Impressionists ravishing but must look long and hard—and always with a sense of nagging confoundment—at a Cubist Picasso, trying with all her might to get the idea. She stands there waiting for the surprising new sensation, the new thought, the new emotion, and when it won’t come, ever, she chides herself for being inadequate and lacking . . . what? She chides herself for not even knowing what it is she lacks. Art that smacks of modernity leaves her not merely puzzled but disappointed in herself. She would love for Picasso to matter more, perhaps to transform her.

Because of all this, the way people in New Haven treated my wife was constantly, explicitly awful. They treated her like some sort of confused, erroneous thing I’d said, something under review, with corrections expected any minute. They treated her like we’d gotten married out of desperation, or like our relationship was purely about sex. Sometimes I’d emerge from a dinner party gasping from all the condescension. That’s when I’d think back to Roth, and the way the first part of The Dying Animal ends. The girl who “finds culture important,” Consuela Castillo, discovers that Culture, with a capital “C,” is just a way for the intellectual paragon she’s sleeping with—our friend, the narrator—to admire himself, his ego protected from the slightest disturbance or threat.

She writes him to tell him off.

“You’re always playing the wise old man who knows everything.” Shouting: “I saw you just this morning on television, playing the role of the one who always knows better, knowing what is good culture and what is bad culture, knowing what people should read and what they shouldn’t read, knowing all about music and all about art, and then, to celebrate this important moment in my life, I have a party, I want to have a wonderful party, I want to have you around, you who mean everything to me, and you’re not there.” And I had already sent her a present, sent flowers, but she was so furious, so angry . . .“Mr. Arrogant Intellectual Critic, the great authority on everything, teaching everybody what to think and setting everyone right! Me da asco!”

That’s how she ended it. Never before, not even affectionately, had Consuela availed herself of Spanish with me. Me da asco. Ordinary idiom meaning, “It makes me sick.”

This isn’t original with Roth; it’s not even close to original. I now know that it’s pretty much ripped off, right down to the imprecation in another language, from Jean-Luc Godard’s film Contempt. It’s the final scene, where Camille finally speaks her “mepris” for Paul and everything he’s become.

But when I read The Dying Animal, I didn’t know Contempt, so Consuela’s letter hit me with considerable force. In my second marriage, it serves as a reminder that I care more about what my wife thinks of my writing, and what she thinks about the movies we watch, and so on, than I do about all the other opinions in the world. Opinions about art, about her, about why we’re together: maybe they would have really seeped in, and disturbed our bliss, if I’d had no proof that somebody else knew a woman like my wife and thought her feelings mattered greatly. Roth delivered that much to me. At certain points in my life, he’s made living it easier. Now that we’re really at the end of the age of print, most novels are luxurious signifiers. They symbolize a certain reader’s free time or elevated sensibility. They’re peripheral; their batteries are nearly dead. But it still gives me pleasure to remember the way fiction used to sing out—particularly the censored, controversial, bohemian books, from writers like Philip Roth, that glittered with strands of razorwire.

Roth the unrepentant moralist. Roth living “the life of the mind,” reckless and precarious, merging orgy and midrash—who gets angry about him now, or is really shocked by his books? While he lived, they said of him, “This person came as a sojourner and he sets himself up to judge!” They still say it about his biography. But I remember him my own way: “In Sodom there lived such-and-such a man. When he was good, he was very good. When he was bad he was better.” This man traveled to a green, prosperous land. There he set up his tent. The world he knew—a world where nothing could be more certain or prestigious than the Nobel Prize he couldn’t seem to win—seemed to him like it was going to exist forever. So he ignored it, insulted it, and wrote great, angry books about it, until almost its very last days.