Five years ago, when Tao Lin turned 30, his third novel Taipei was released to greater acclaim and attention than he’d ever enjoyed previously. He begins Trip: Psychedelics, Alienation, and Change, his first book of original material since Taipei and first non-fiction book, recounting the days in late 2012 when he was “zombielike” and adopting a “whatever it takes” attitude toward abusing amphetamines and benzodiazepines in an effort to finish the final draft of Taipei. He found this video of Joe Rogan enthusiastically talking about DMT. The video is a YouTube classic, with one of my favorite lines ever from a morning zoo style radio host encouraging Joe Rogan to go on: “Keep going bro, I’m a student right now.”

Rogan mentions Terence McKenna, a deceased scholar of entheogens, shamanism, alchemy, metaphysics, and botany. McKenna has become something of a psychedelic martyr, a man who died at 53 of brain cancer and left behind hundreds of hours of recordings of his lectures and thousands of pages between his many books on aboriginal and ancient use of naturally occurring psychoactive plants and fungi, among many other things.

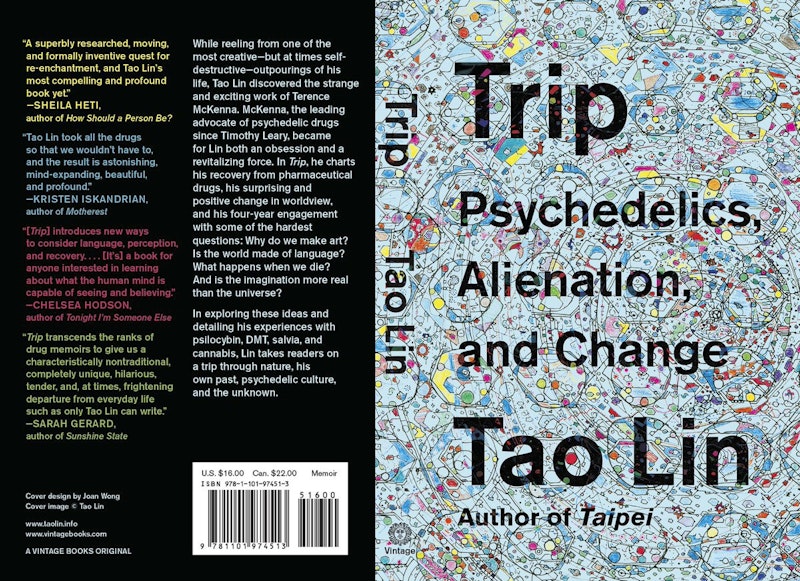

Trip follows Lin’s “recovery” from “the surreally crude dead zones of pills, tablets, creams, pastes, sunscreens, processed foods” that define life in the modern world of the 21st century. Gradually abstaining, with surprising ease, from amphetamines, benzodiazepines, MDMA, opiates, opioids, and various research chemicals, Lin’s daily life stabilizes from feeling suicidal and panicked to a sustained high, so strong that he regularly weeps with joy thinking about his parents and friends and recalling previously repressed, painful memories.

Trip is as much a crash-course in psychonautics and the poisoning of the first world population with pesticides and growth hormones as it is a memoir about recovery and addiction. Because all of Lin’s work is thinly-veiled autobiography, I found the unadulterated narrative and presentation of Trip more enjoyable and moving than any of his previous books. It also functions as a companion piece or semi-sequel to Taipei, which climaxes with “Paul” taking mushrooms and becoming convinced that he has died.

Trip is broken up into 10 parts focusing on Terence McKenna and his ideas, why Lin became obsessed with him, Lin’s drug history, why psychedelics are illegal, and all of the naturally occurring drugs that Lin began using or continued to use during his recovery: cannabis, salvia, psilocybin, and DMT. The book ends with a novella-length epilogue written in the third person, where Lin travels to Northern California to visit McKenna’s ex-wife Kathleen Harrison to interview her and take a plant drawing class.

Lin’s deadpan prose remains, but it’s never robotic, and he’s frequently hilarious, particularly when describing his paranoia, whether it’s in jury duty or preparing to smoke DMT with an online friend he’d just met in person for the first time. He thinks, likely due to mild brain damage from amphetamine abuse, that everyone is a CIA agent: after smoking DMT, his friend enthuses about the video they took of him tripping, and he writes that “My sense of victimization, of being targeted and masterfully defeated… increased considerably.” Eventually he’s able to view these delusions with amusement, even egging on people he suspects may be CIA agents out to get him.

Trip is well-researched and dense with scientific material and data, but remains enjoyable to read, despite or because of Lin’s methodical prose: “Part of what he was experiencing, as an animal, was his feelings, a large part of which came from the ever-changing statuses, quantity, distribution, and level of functioning of his neurotransmitter receptors, of which he had at least 141 types, including nineteen purinergic, fourteen serotonergic, eleven adrenergic, nine opioid, five dopaminergic, and probably three cannabinoid. His feelings existed with what his other receptors, like ones for vision and olfaction and other senses, detected.”

The book functions best as a memoir through recovery from drug addiction and an appreciation for ways of living and modes of being that are easily accessible, like using cannabis, eating healthy, non-processed foods, avoiding consuming products with additives, preservatives, and pesticides as best one can, and to use psychedelics like psilocybin mushrooms, salvia, and even DMT as tools to connect with an ancient consciousness that extends billions of years into the past.

It’s not a gloomy or dour book, and Lin avoids explicit anti-vaccine and fatalistic moaning about Monsanto’s stranglehold over the earth in favor of a brighter outlook. In the book’s epilogue, Lin writes, “He had the opportunity to experience emotions at this gradation of subtlety and level of control and awareness—a gift of complexity that could be overwhelming to almost unbearable, sometimes making him cry from appreciation and incredulity and confusion—because billions of his ancestors’ siblings had died young, leaving more resources for the survivors: his ancestors.”

It’s an encouraging epiphany because it’s accessible right now. Trip doesn’t tell you to “leave society” and go live in the woods and eat tree bark and swing from branch to branch. It’s not judgmental: as a former heavy user of synthetic drugs, Lin has an innate compassion and empathy for our first world predicament, which does seem inescapable: that we as a species are “degenerating” due to the effects of the Industrial Revolution and factory farming and chemicals that are all a part of us in 2018. When Lin loses his phone toward the end of the epilogue, he remembers the sometimes trite but true advice to “Be here now,” and modify your behavior if you’re unhappy and able. It’s a moving book and Lin’s best work by far.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith