The weakening of the strong force of soft power is Time dilation, where content deteriorates and excellence declines.

The loss is visible in and outside the pages of Time, a month before the magazine’s centennial and a lifetime after the death of the American Century.

The loss is the obliteration of a certain idea of America, from the outposts of the New Frontier, the buildings born during the Eisenhower administration, to the greatness of the Time-Life Building.

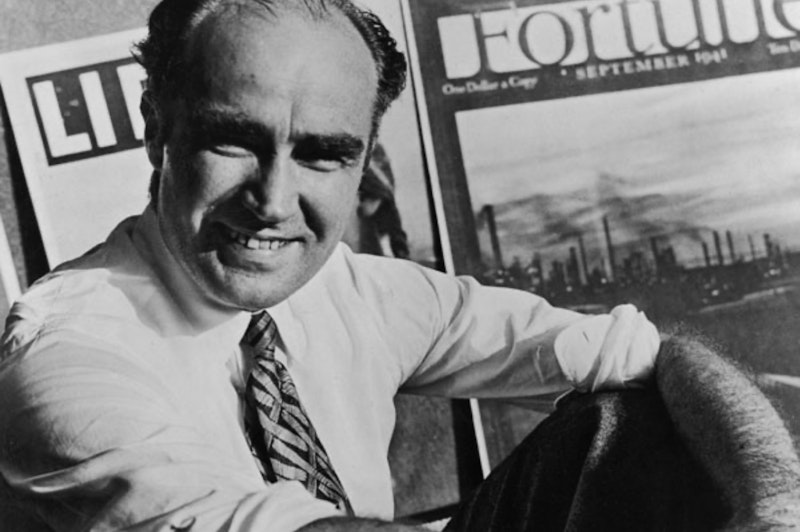

The loss marks the end of Henry Luce’s empire, of the view from his office on the 34th floor of 1271 6th Avenue—Avenue of the Americas—and of his favorable view toward conservative liberalism.

The viewpoint is regional on the outside, a Regionalist portrait of the artist as a 36-year-old man, and a celebration of the International Style throughout the West; of John Updike aiming his mind toward a vague spot a little to the east of Kansas, a full-face view in front of a wave of grain, while Time illustrates an excerpt of his novel.

Here is a core of discovery, by a corps of discoverers, under the auspices of Luce and clerk; a Henry Luce expedition into the fictional town of Tarbox, Massachusetts, where Joy Creek snakes west of Temperance Avenue and Prudence Street forms a fork in the road.

Here is a map by Robert M. Chapin Jr., chief cartographer of Time and mapmaker of “Two Worlds” in red and blue.

Here is a 136-page issue of Time, with ads for wine (Paul Masson) and spirits, from Cutty Sark to Canadian Club to Johnnie Walker Red, from Old Crow to Old Charter to a splash of George Dickel; with ads from the Big Three, and American Motors, to two pages for Hertz; with the last page for two cowboys smoking Marlboro Reds.

Go from Updike’s vision of a town in Massachusetts to a Massachusetts senator’s vision for America, as the former commander of a boat—the hero of PT-109—seeks to captain the ship of state.

Before listening to him speak of a new generation of Americans, look at the “New Face for America Abroad” in Time.

The article is from July 11, 1960, with a map and color photographs of our embassies in Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

The buildings symbolize the promise of peace, and presage John F. Kennedy’s pledge to wage peace.

Here, in marble and mahogany, are works of progress—by the father of the largest public works project in American history, Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Here, as in the lobby of the Time-Life Building, is art for the promotion of culture and the power of the art of cultural diplomacy.

Here, too, is the art of presidential rhetoric, of President Kennedy’s defense of freedom—and of his assurance that this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it.

The glow from that fire no longer lights the world, for the torch is now an eternal flame; for the American Century, with Luce’s admonition to avoid the false and suspicious position of Toryism, and Kennedy’s call to courage—not complacency—because the United States today cannot afford to be either tired or Tory—that time is past.

We are without the lights and literature of giants, just as we are without the architect of Time and the architects from the time of the Americans.

We live in less interesting times.