I’ve been trying to plant seeds by mentioning it here and there that Broadway’s next ticker tape parade should be for doctors, nurses and other healthcare workers slaving during the COVID-19 crisis. However, I’d extend the invitation to delivery workers, food preparers, laundromat workers, and everyday laborers who are continuing to do what they do despite a raging virus that has killed thousands. But who knows when there will be parades or large gatherings of any kind?

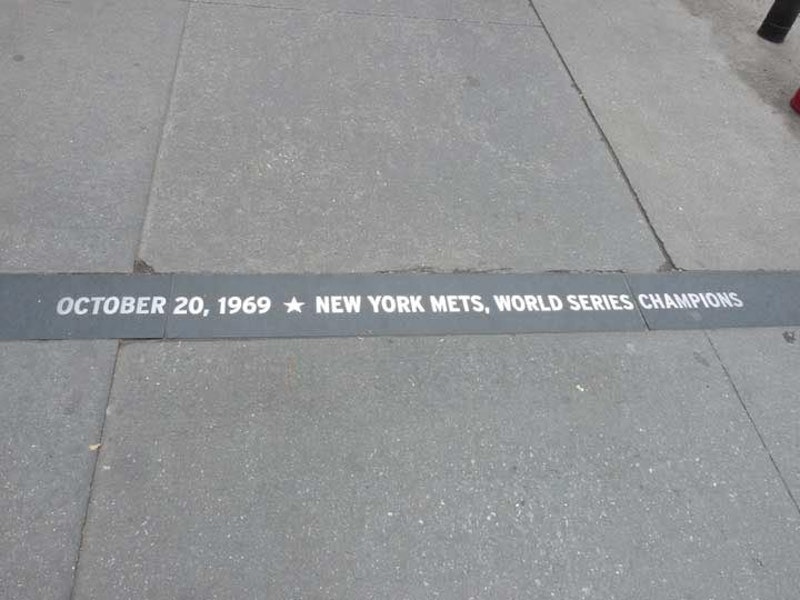

The Downtown Alliance, a business improvement district representing Lower Manhattan, has embedded brass lettering commemorating every ticker-tape parade ever held in New York City, beginning with the first one: A fete on Oct. 28, 1886 to dedicate the Statue of Liberty. “Ticker tape” is an inch-wide ribbon of paper on which a “ticker” machine recorded stock quotes. When volumes of it were released into the outside air, it created a mesmerizing swirling effect. The practice of throwing it out of windows broke out serendipitously during that first parade, and has done so for the more than 2000 parades on Lower Broadway since, helping the street became known as the “Canyon of Heroes.”

These days, shredded office paper is used instead of ticker tape. The Alliance has created a Canyon of Heroes app that serves as a guide to the parades.

New York City’s skyline is the envy of the world, a sight tourists travel from across the globe to see. But in some places, its sidewalks are nearly as interesting, with plaques, art installations, handprints and other markers to commemorate important locations and get your attention. What follows is a rundown of some favorite NYC sidewalk plaques and markers.

One of Manhattan’s most unique monuments gets stepped on thousands of times daily. William Barthman first set up a jewelry shop in the Financial District in 1884, and added a sidewalk clock on the corner of Broadway and Maiden La. in 1899. The clock was designed by Barthman and an employee, Frank Homm. When Homm died in 1917, no one knew how to maintain its singular design, and the clock was replaced with a more customary model in 1925 that’s been in place ever since.

The Barthman Clock has been attacked by vandals and trodden on for years, but it keeps on ticking with the help of an electric motor. An organization known as the Maiden Lane Historical Society set up a plaque in 1928 at Barthman’s depicting what Broadway and Maiden La. looked like that year. In 1946, the NYPD estimated that 51,000 people stepped on the clock every day.

After moving up Broadway a few years ago, the jeweler now has an address in Brooklyn. But it made an arrangement with the current building to maintain the Barthman Clock, even though the unusual timepiece doesn’t have Landmarks Preservation Commission protection.

There’s a hidden city beneath the city. Sewers, electrical wiring, water mains, traffic and train tunnels all pulse and vibrate under your feet as you walk the five boroughs. Other than steam-belching vents, manhole and coal chute covers are the only visible reminder of this underground sub-city. If you walk past them without noticing, you’ll miss a lot of delicate cast-iron artwork and a hint of the past history of New York City.

Some of New York’s most gorgeous cast-iron covers led to coal chutes. Before central heating was instituted—fairly recently—most New York City buildings burned coal for heat. The chutes led to conduits that brought the coal directly into the burners. Many of these coal chute covers bear the names and addresses of their long-lost manufacturers.

The small building hosting Village Cigars at Christopher St. and 7th Ave. S. has had this small mosaic triangle directly in front of the store entrance since the building was constructed shortly after 1912. It’s likely the smallest piece of private property in the city.

There used to be a five-story residential building on Christopher St. called The Voorhis. It was condemned in the 1910s to make way for the IRT subway, which also extended 7th Ave. south from Greenwich Ave. However, the Voorhis’ owner, David Hess, refused to surrender this small plot to the city to become part of 7th Ave. South’s new sidewalk. The Hesses created this mosaic to let everyone know of their small victory against the city.

Village Cigars moved to its present corner site in 1922, and bought the 500-square-inch property from the Hesses for $1000 in 1938. The mosaic has stayed put, while Village Cigars has become an iconic symbol of New York life. So the Hesses no longer own their little triangle in the sidewalk, but there it remains, a monument to good old-fashioned spite.

Lucille Lortel, known as the Queen of Off-Broadway, acquired the old Theatre de Lys at Christopher and Bedford Sts. in 1955. Her wealth allowed her to bring works by playwrights such as Terrence McNally, Edward Albee, Jean Genet, Eugene Ionesco and others to prominence for the first time in the U.S. “The Threepenny Opera,” by Bertolt Brecht, had its proper American debut at the de Lys in 1954; the theater was renamed for Lortel in 1981. Outside the theater is a mini-walk of fame commemorating famed authors and playwrights such as Christopher Durang and Ring Lardner, who had their works performed inside.

Everyone’s heard of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, where generations of film stars have signed their names and imprinted their hands in wet concrete. We have our own mini-version of Grauman’s Chinese in the East Village.

Theatre 80, at 80 St. Marks Pl. near 1st Ave., used to run movies from the golden era of Hollywood, the 1930s to the 50s, and served coffee in china and cake on porcelain. Former actor and singer Howard Otway bought the onetime speakeasy and turned it into a revival house in 1971. His dream was realized in August of that year, when he threw an old-fashioned Hollywood premiere party to celebrate the opening. He invited several old-time Hollywood stars and asked them to make their marks on the new sidewalk outside the theater. By 1980 Joan Crawford, Joan Blondell, Allan Jones, Ruby Keeler, Gloria Swanson, Myrna Loy, Kitty Carlisle, Dom DeLuise all visited and managed to leave mementos.

The theater is now run by Howard’s son, Lorcan Otway, as a performance space and the home of the Museum of the American Gangster. When the sidewalk was repaired in the 1990s, the fate of the stars’ signatures was in doubt, but the theater managed to preserve them by moving them slightly.

Though the Second Ave. Deli has moved uptown from the corner of Second Ave. and E. 10th St., the sidewalk outside its former location still boasts The Walkway of Yiddish Actors, an homage to the old “Jewish Rialto” of theaters featuring plays in Yiddish, when the language was common among immigrants from Eastern Europe. The walkway was installed in 1984 by deli owner Abe Lebewohl. The names Fyvush Finkel and Molly Picon, who made many TV appearances, may be recognizable to American audiences. Though the walkway is showing its age after 35 years, the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation is attempting to raise funds to preserve and protect the original stones, while installing replicas in their place.

Lebewohl, the longtime owner of Second Ave. Deli (he founded it in 1954) was shot and killed in an unsolved robbery on March 4, 1996. The deli closed at its original location, but later reopened in two Midtown and East Side locations, 162 E. 33rd St. and 1442 1st Ave. (at E. 75th St.). An original “2nd Ave Deli” neon sign can be found at the City Reliquary in Williamsburg.

For two blocks between 5th and Park Aves., east of the New York Public Library, the sidewalks of E. 41st St. on both sides of the streets are festooned with brass plaques featuring literary quotations. The plaques are the work of sculptor Gregg LeFevre and were installed in 2004 by the Grand Central Partnership group, working with NYPL. The 96 plaques (each appears more than once) quote 45 writers from 11 countries. They were chosen from submissions by a consortium that included NYPL, the Partnership and the New Yorker magazine.

The aphorisms include:

“Where the press is free and every man able to read, all is safe.”

— Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) in “Letter to Colonel Charles Yancey”

“I want everybody to be smart. As smart as they can be. A world full of ignorant people is too dangerous to live in.”

— Garson Kanin (1912-1999) in dialogue, “Born Yesterday”

“If you do not tell the truth about yourself, you cannot tell it about other people.”

— Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) in “The Leaning Tower”

A full list can be found at NYPL’s Library Way page.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)