Who wouldn't be a friend of a library?

I just wish there was another way to put it. Even in the age when "friend" is now a verb, the phrase has a vanilla saintliness that makes me feel creepy and mean-spirited the way I do at a Quaker or Unitarian service. Unfairly, I sense them hectoring and beseeching me at the same time.

Still, I suppose I am a friend of libraries. I've always liked them, and I especially like the Berkeley Public Library in what has now, after 15 years, become my hometown.

The branch I live close to, the West Branch, is a goldmine because the new book shelves don't get filleted in the same manner that they do at the swanker North and Claremont Branches, the latter a eucalyptus ember's distance from the storied hotel of the same name, now a spa-cum-tennis-and-swim-club, formerly a rundown near-SRO.

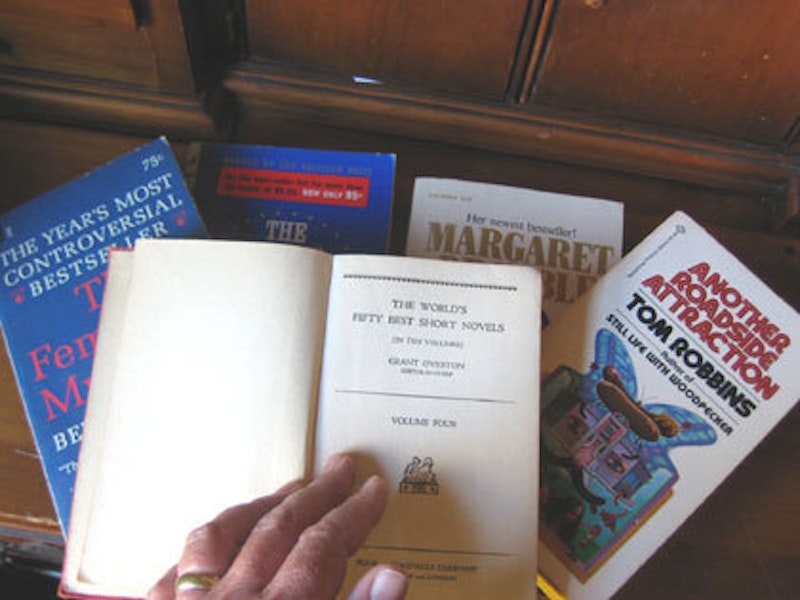

My husband Jamie and I go to West Branch about once a week, to pick up books and records and DVDs and CDs we've reserved online and to paw through the return trolleys and new book shelves. It's a tiny building, and in the crowded entry room, along with the piles of tax forms, adult school catalogs, lists of public showers, hot meals, paratransit services, and organic low-cost school lunches, sits a small bookcase, four or five shelves high, with a little vault next to it where you can deposit your payment for any of the books you purchase. The proceeds go to the Friends of the Library, and all titles are 25 cents.

I don't know what got me started, but sometime about six or seven months ago, I began pausing at the Friends bookcase to see what was on it. People just dump their old books. The library takes them as long as there is not too much underlining, mold or water damage, and that the covers are intact. I am guessing that the Friends' main bookstore downtown has first crack. They have a real book store there, with hardbacks cataloged by subject and selling for varying prices, all more than 25 cents. The books on the West Branch Friends sales shelves are the ones that no one thinks are worth hauling around any more. This is their final stop.

The idea that I would buy a book to bring home was apostasy in the house in which I was raised. One of my earliest Christmas memories is of my mother Ruth railing about "another damn book in the house" as one of the six of us tore the wrapping off the gift from the Doubleday store introduced into the family by an unknowing outsider. Our living room and den were walled with bookshelves, crammed with Dad's share of the huge library his father had collected. He told me of growing up in a house where the books were shelved two-deep to keep them off the floor.

I had been told that paying money and bringing a book home is anathema. Even if the book is a slight paperback and costs a quarter. So it took me a couple more weeks to get over Ruth's training.

When I saw a copy of The Feminine Mystique, I thought, you know, it's almost an iconic object, even if I don't read it. It is designed beautifully: the cover is a dark, midnight blue, the sans-serif DELL, also in blue, in the upper left corner, encased in a full-bleed black box. Opposite is the price in a white elegant font: 75c. The Feminine Mystique in red, of course, topped by a tagline in white uppercase: "THE YEAR'S MOST CONTROVERSIAL BESTSELLER." Betty Friedan's name is below the title, no "by" needed. And, the real capper from my point of view, a blurb from Ashley Montagu, one of the champion pop-anthropologist explainers who seemingly made a fortune on books depicting the revolutions, sexual and otherwise, that were playing out in the culture of the time. "The book we have been waiting for...the wisest, sanest, soundest, most understanding and compassionate treatment of contemporary American woman's greatest problem...a triumph."

It came out in hardback in 1963. It went paperback in '64. This was the fifth edition Dell printed that year: the first in February, second and third in April, fourth in June and this one, in November. Friedan was a married mother of three, Smith College graduate and journalist for the likes of Good Housekeeping, Harper's, McCall's and Reader's Digest, according to the blurb. That, after all, was where an ambitious woman with kids would find an outlet. (Remember, Sylvia Plath won the poetry contest in Redbook.)

I had to be careful when opening the pages: they're yellowed, and the glue in the binding is cracking. I haven't really done much more than dip into it. But someone has marked it up. There seem to be two or three annotators.

One used a blue ballpoint to make precise dots at the start of lines. Here's a passage so marked from pages 24-25.

And strange new problems are being reported in the growing generations of children whose mothers were always there, driving them around, helping them with their homework—an inability to endure pain or discipline or pursue any self-sustained goal of any sort, a devastating boredom with life. Educators are increasingly uneasy about the dependence, the lack of self-reliance, of the boys and girls who are entering college today. "We fight a continual battle to make our students assume manhood," said a Columbia dean.

Even Friedan doesn't pick up on the embedded assumptions in the dean's "manhood" fixation. Columbia, after all, was an all-male school at the time, like Harvard, with a sister school, Barnard, whose female inmates were permitted to have access to Columbia classes, if there was room.

I am reminded of the resentment expressed to me and my fellow women at Yale, the second freshman class in which women had been admitted, for "ruining the Yale experience" for male classmates and for being called on by our professors to give the rest of the class "the woman's point of view." I also recall how the university restricted women in those years to 250 each class, so that Yale would not renege on its promise to produce "1,000 male leaders" each graduation. Of course, that meant there wasn't quite enough room for us, so we were squirreled away in spare rooms around the campus. We did get a nice sex ed/ob-gyn service, but it was so over-subscribed that the only way to get an appointment was through pulling strings, which I did via my roommate Marilyn, who knew everybody by dint of her having the job of checking in all the freshmen at the main dining hall.

This was the same time that saw the publication of the student-written handbook, Sex and the Yale Student, illustrated with Brancusi's "The Kiss" on the cover. (The figure with the bulge is the woman.) My roommates and I thought the stone figurines were a pretty good choice, given the romantic abilities of most of our fellow Yalies.

They fell into three groups: the old school types (who had been surprised to see us arrive), the over-achieving nerds (who had no clue about how to deal with women) and the self-proclaimed "hip" druggies (who knew that a steady pot or acid connection could work wonders for getting women).

First, the old school. If they didn't resent us for messing up their all-male club, they resented us for tinkering with the delicate chemistry of the Mixer, wherein suitable females from often academically inferior schools were bused in for ostensibly sober dances. The object, of course, was to get drunk and laid, not necessarily successfully, or in that order. My roommates and I loved to go to them and hang out with the upper classmen and then, when they were lubricated enough to get up the nerve to ask us back to their room, tell them, no thanks, we'd just head back to our residential college. An entire evening's efforts wasted, for who would want to encounter someone you'd screwed the night before in one of your classes or the Cross-Campus Library carrels? The mixer thing was so perverse: some of the better women's schools were in the rotation, and more than one old-time Yalie found his mate from even the inferior schools, but there was a sense that these women were the "testers" for our young leaders of tomorrow to lose their cherries on before hooking up with the real, properly lineaged debutantes from Park Ave. and Connecticut.

The second group were the nicest: they were really smart and really clueless about romancing women, especially women who, they were intelligent enough to appreciate, must be at least four times smarter than they were since only a quarter as many women applicants were admitted. In fact, Yale turned away nine women for every one it admitted that year. They were also smart enough to know that given the more than four-to-one ratio of men to women (since there were two classes that were practically all male), their odds of scoring were so numerically low that it was hardly worth the effort. This led to some great friendships with some guys who seemed hopelessly unsexy, but who grew up and went to med school or law school and ended up marrying pretty wives who had no idea how hopeless their rich successful husbands had been as undergrads.

The third group was in a way the sneakiest and smarmiest. They were dominated by upper classmen, like the ones who'd led the SDS marches the spring before, and, in those days of the draft and draft deferments, grad students who were extending their avoidance of having to go to Vietnam by enrolling in more school. These were the people who populated the Forestry and Divinity schools. They had great drugs, had cars, were old enough to buy booze legally and often lived in ramshackle remote houses on the Long Island shore west of town where the parties could go on all night.

A number of the books I've picked up are ones that I either thought I had read when they came out or meant to but didn't. The Ice Age by Margaret Drabble is one of those, the appeal due partly to the fact that "Drabble" is such a Dickensian word. It is a ripping read in a strangely suffocating way. Like Dickens, Drabble writes in broad satire clothed in commentary and intricate plotting. I won't push the analogy any farther: the resemblance is fleeting but pleasant. I got through it in the course of a long weekend vacation down to the Central Coast. It was well-suited to reading in our motel room 100 yards from the breakers in Cayucos because of the constant thrum of doom punctuated by darkly hilarious skewering of the over-educated Oxbridge sell-outs who, even when broke, manage to afford plane tickets to anywhere the story requires them to go.

As much as I enjoyed The Ice Age, it's a good thing I saw it on the shelf like this:

because the cover that was used to sell it on the airport paperback racks looked like this:

and I'm enough of a snob that my eyes would have skipped over it thinking it was a rip-off of Valley of the Dolls.

It's one of those covers where I had trouble matching the characters with the illustration and, after a bit, gave up because I didn't want them to look like that in my mind.

I can see what the marketers were up against. Drabble opens with a passage from Milton's Areopagitica (1644), written in opposition to efforts by the government to control publishing by licensing printers. The passage Drabble chooses invokes images of England as "a noble and puissant Nation rousing herself like a strong man after sleep, and shaking her invincible locks," an eagle among "timorous and flocking birds" who emit an "envious gabble" that predicts a year of sects and schisms."

That's followed by an excerpt from the Wordsworth sonnet, "Milton!, Thou shouldst be living at this hour: England hath need of thee."

Not exactly 1977 bodice-ripper material.

In addition to the pleasures of reading Drabble's takedown of the politically correct moneyed classes of her time, a current reader can enjoy just how thoroughly things haven't really changed. Here is the main character musing on his future as he looks down at the acres that surround a fine old country house he bought at the top of the market with finacing based on an investment with friends that has turned bad.

Suddenly, overnight, the property market collapsed. It was almost as though it had been waiting for him to sign the contract.

The collapse had been dramatic, and had affected others more severely than Anthony Keating. He, a mere novice in property, watched events with dismay and mounting alarm. What has happened to those days of easy money in the early seventies, what had happened to the boom, to all those spectacular profits? Why had all the confident experts been so taken by surprise? ... Go for growth had been the slogan, and everybody had gone for it. Now some were bankrupt, some were in jail, some had committed suicide... Old men were convicted of corruption and hustled off to prison, banks collapsed and shares fell to nothing.

The same year, another, infinitely sadder and more earnest evocation of then and now, came out in Bantam paperback, Friendly Fire, by C.D.B. Bryan. This was the time when Vietnam was still fresh, I could remember watching my fellow Yalies on the night the lottery numbers were called out in what must have been 1972.

The book itself is a bit of a slog. Bryan never quite lived up to the (now-defunct) Washington Star's blurb likening the book to Truman Capote's In Cold Blood, which came out in '66. But that is part of the point. There is little suspense. It's clear pretty soon that the favorite son of the fifth-generation Iowa farming couple was killed by U.S. artillery in a fairly common exercise that went wrong this time. But the point of all 435 dense pages is to show the heartless stupidity of the government when it is The Government, not our government, which was the sense most of the time in the 50s, 60s, and 70s.

A key source and character in their son's death was a then-obscure Lt. Col. Norman Schwarzkopf, whom Bryan interviewed extensively, and who comes off as a regular Army guy who did nothing terribly wrong and in fact probably did things exactly as well as they could be done under the circumstances. The circumstances are that the draft was unfair, that the sons of politicians and other well-connected persons did not get drafted or, if they did, they didn't go to Vietnam, or, if they did, didn't see combat very often, and that the way the war was conducted in the field was inefficient, ineffective and inhumane.

Mary Gordon was another star of the feminist 1970s wave, whose first best seller, the 1978 Final Payments, landed on the Friends shelf. It's another one with the hottie cover, and inside even more insulting: a soft-focus painting of a handsome man with his arm around the shoulder of a woman, who is leaning in to his protection, wearing what looks like his suit jacket draped over her shoulders.

The inside cover's a sellout on two fronts: because of its completely anti-feminist message, and its false promise of pretty sex. While there is sex in Final Payments, it's typical guilty Irish sex, in this case, between Isabel Moore, who has spent her 20s literally indoors, caring for her paralyzed Jesuit-trained father in their dark, musty house in Queens, and a couple of different Irish Ken dolls. In another seemingly obligatory nod to the times, Gordon makes Isabel's brave best friend who married well, if dangerously, a sort-of out lesbian. In other words, the sex is the weakest part of the book and makes me think it was dreamed up by Gordon to sell the rest of her message, which is much less conventional.

Gordon's voice is deeply Catholic only as a person writing at the end of belief can be. This is what makes her a 70s writer, I suppose.

The book opens with Isabel's father's funeral, when Isabel will have to confront the next phase of her life, "invent an existence for myself."

My father's life was as clear as that of a child who dies before the age of reason. They should have had for his funeral a Mass of the Angels, by which children are buried in the Church. His mind had the brutality of a child's or an angel's....

He loved the sense of his own orthodoxy, of holding out for the purest and the finest and the most refined sense of truth against the slick hucksters who promised happiness on earth and the supremacy of human reason.

In history, his sympathies were wtih the Royalists in the French Revolution, the South in the Civil War, the Russian czar, the Spanish Fascists. He believed that Voltaire and Rousseau could be held (and that God was at this very moment holding them) personally responsible for the mess of the twentieth century.

Gordon's was another name I probably heard my mother recommending to me, while I was too busy being a twentysomething writer myself to read contemporary fiction. It was enough to read the reviews in the Times, and I probably didn't do that very often since I didn't get the paper and only read it when I was at my parents'.

I looked up the review that ran when Final Payments first came out in 1978. It's written by Maureen Howard. She's another name that floated at the edge of my consciousness at the time. A John Leonard recap of her career in a review of her 2001 three-part novella, Big as Life, is worth reading for the history of the last three decades of 20th century American writing. I think I'll look for her stuff on the Friends shelf next time I go to West Branch.