“People want something to vote for, not something to vote against!” This is a common social media mantra, especially on the left where many are (understandably) sick of being told they can’t criticize Joe Biden because Donald Trump is worse. It makes an intuitive sense that voters want promises of a better life rather than threats of a worse. Positive emotions are uplifting and make you act. Negative emotions are enervating and paralyze you. Right?

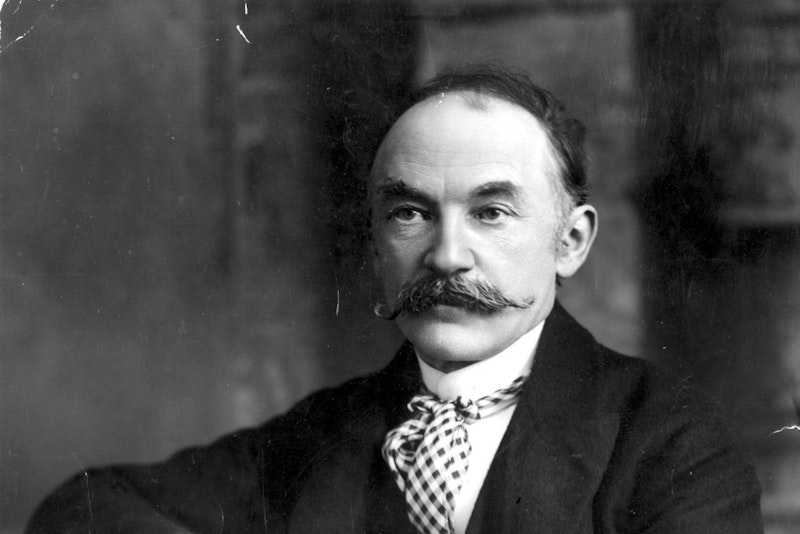

Thomas Hardy had some doubts. Hardy’s best known as a novelist, but also produced a great many poems, including the sonnet “Hap.” It was written in 1866 when he was in his mid-20s.

Hap

If but some vengeful god would call to me

From up the sky, and laugh: “Thou suffering thing,

Know that thy sorrow is my ecstasy,

That thy love's loss is my hate's profiting!”

Then would I bear it, clench myself, and die,

Steeled by the sense of ire unmerited;

Half-eased in that a Powerfuller than I

Had willed and meted me the tears I shed.

But not so. How arrives it joy lies slain,

And why unblooms the best hope ever sown?

—Crass Casualty obstructs the sun and rain,

And dicing Time for gladness casts a moan…

These purblind Doomsters had as readily strown

Blisses about my pilgrimage as pain.

Hardy’s talking about faith, or lack thereof, rather than about politics. He’s wishing he believed in a deity—but not a benevolent one. Rather, the twist of the poem is Hardy’s praying to be singled out for scorn and misery by a “vengeful God.” If only a voice would speak out of the heavens and declare—Screw you Hardy, I am going to ruin your day!—the poet would feel vindicated and even empowered. “Then would I bear it, clench myself, and die/Steeled by the sense of ire unmerited.”

The poem understands that people aren’t motivated solely, or even primarily, by hope. The speaker doesn’t imagine drawing solace from an awaiting heaven. Instead, he imagines drawing solace from implacable opposition and his own sense of outraged injustice. It’s better to have an all-powerful ogre enemy than to be crushed beneath indifference—“purblind Doomsters” who had just as soon given him joy and long life as Covid-19.

Hardy wanted an enemy to hate. And no wonder because people love to hate their enemies. Nothing feels quite as exhilarating as a sense of battling against a remorseless, mighty opponent, who hates you out of sheer evilness and exults, “Know that thy sorrow is my ecstasy!”

You can see the dynamic of “Hap” throughout our discourse and politics. Conservatives boast about refusing to get vaccines to spite the left, even as they’re on their deathbeds. Liberals cheer when those conservatives die, even though fewer vaccinated people hurts everyone. Or look at the massive voter turnout in 2020. Trump polarized both right and left, and the result was a record-breaking 66 percent of eligible voters at the polls, the highest rate since at least 1980.

Theological metaphors for this-world problems have their limits. Hardy’s demonic deity doesn’t exist; the point of the poem is that evil’s arbitrary and unwilled. But that doesn’t mean that there’s no evil in the world. The fact that we get some comfort from imagining evil in some cases doesn’t mean we’re imagining evil in all cases. People aren’t gods, but they’ve still managed historically to do horrible things to each other. Trump was separating children from their parents to terrorize immigrants; Biden’s defending those policies in court today. Even the recognition that suffering is arbitrary can end up as an excuse for malice—as with Covid, where the bland claim that nothing can be done justifies passivity while the piles of corpses rise.

Hardy recognized that people are motivated often powerfully, and derive comfort from, hate. That’s an insight that still makes people uncomfortable. But the impulse to fight against evil isn’t bad. It’s not good either. It’s just true.