We’re in the middle of a heat wave. Every window in our house is wide open to coax any merciful breeze that crawls by. As soon as I open my eyes I brace myself, remembering yesterday’s scorcher and the day before that and the day before that. The temperature has been over 100 and you just know it’s gonna be another hot one.

But this early morning, it’s almost cool and amazingly quiet. No sounds of snorin’, no sounds from the radio or TV, no horns honkin’ or tires screechin’ or people yellin’, no birds squawkin’ or dogs barkin’ or cats fightin’ or babies cryin’ or noise from the train yards or factories at the end of the street. Nothing except for the hum of the refrigerator.

I know it won’t last, this quiet and the slight cool air of the morning, but I just want to hold onto it and make it stretch. It’s like some kind of a truce, a sort of settlement has been reached in our house and on our block and in our neighborhood. But I know it can’t last.

Maybe someone else, one of my brothers or sisters or my mom or dad, is awake too, like me, just lying still in their beds. They might even be pretending to sleep. We do a lot of pretending. We pretend to know things we don’t and to not know things we do. We pretend what matters, doesn’t, and that we don’t care about the things we honestly do. We pretend things that aren’t funny are and that we get the joke when we don’t. And we pretend to have a plan and that we know our lines.

So who knows if it’s real or pretend sleep that has them all still and quiet but I seize this moment to dress in a hurry and sneak outside. I stand barefoot and stretch at the bottom of our back porch stairs by the banana tree that shades the imprints of feet in the cement. I put a foot in the impression of my big cousin Juno, trying to imagine him when he was my age and our feet were the same size. Alongside his footprints are those of his sister Rachel and the hand and footprints of my older sister Letty and cousins Linda and Dickie and a date scratched in the cement from a time before I was born.

I stretch and look at the cloudless sky and walk down the driveway toward my grandparents’ house. The cement is still cool, but in a few hours I’ll need something to keep my feet from frying.

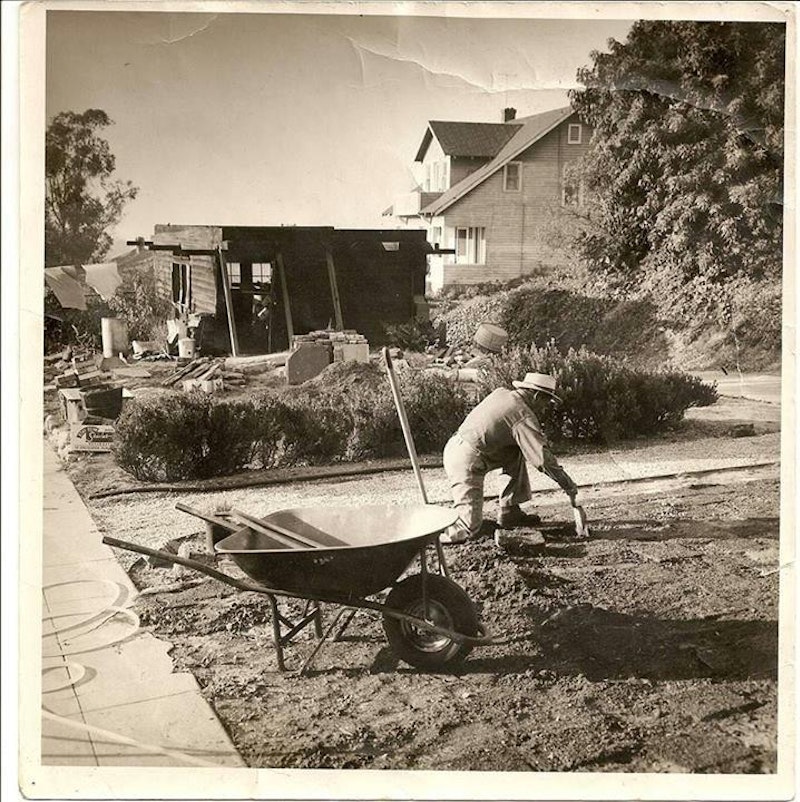

My granddad owns this property. The front and the back houses plus another down the street where my uncle Pete and his family live. My granddad built the back house where I live. Friends and family helped with the carpentry, plumbing and electrical, but the cement work, that was all his. The foundation, the porches and stairs, the long driveway, and the wide yard between the houses were all done by his hand.

In fact he did most of the cement work that could be done on our block. He was best as a finisher, the guy responsible for smoothing and leveling the pour. When he was done there’d be just enough of a grade that water wouldn’t ever pool. He was never without work, not even during the depression in the 1930s.

But I didn’t know any of that then as I walked from the back to the front house. It was long before I was alive, so how could I have known? I didn’t know then how he came to have a limp and needed a cane to walk. Years later I learned that he was cleaning the walls and blades inside a big commercial cement mixer when someone accidentally hit a switch, starting the blades spinning in opposite directions. He was cut badly before his cries were heard and the machine shut down.

I didn’t know any of this then as I worked my way to the front house, having nothing particular in mind. I didn’t know much of anything then and wondered years later if anyone would remember seeing a boy walking with an old man in his piss-stained pants and beat-up hat, one hand on the boy’s shoulder and the other on a cane moving slowly, inch by inch along the sidewalk he had poured and made smooth. Would anyone remember them walking to Pierre’s Liquor Store to get the old man a couple bottles of muscatel past the walls made of river rock and across Cypress Ave. where people in their cars honked impatiently as the two slowly crossed?

The boy glared back at them—a dare to keep on honking. In years to come they’d never remember the kid and the old drunk. Why give them a second thought? That summer though, that summer morning I found Granddad sitting on a rocker smoking a freshly rolled cigarette from his can of Prince Albert tobacco. “Hola Panzón,” he said. His nickname for me cause I’m kinda fat.

“Hola Abuelo,” I said and sat with my back to him on the green painted cement steps of his front porch and pointed my face toward the sun, looking at the veins through my closed eyelids at a blood-red world as the rays caressed my face. There are some things you are just not supposed to look at directly.

Then again, you just can’t rely on your eyes to tell you everything. That morning in the company of my granddad and in no rush to see the summer unfold, there was a contained richness. There was only the up and down of the heavens and the earth. Or in this case, the holy cement beneath my feet.

Some kids may have asked the basic questions of their grandfathers. Why’s the sky blue and the sun yellow or where do clouds and babies come from and what was I before I was born?” But not me. Not when the mystery was right there beneath my feet.

And so I asked, “Granddad, who made the sidewalks?”

And he answered right back at me without pause, “I did.”

And I didn’t breathe for a few seconds or it could have been minutes. That’s when I knew my granddad was God. I don’t remember either one of us saying anything after that. Really, what was there to say? I mean just a moment before he was only my granddad, a mere mortal, an old piss-pants boracho and now I’m different and he is so much more.