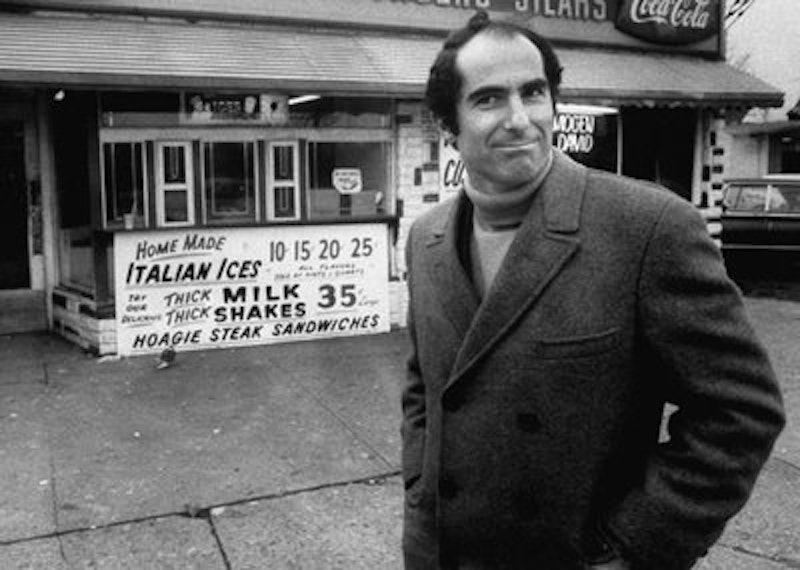

Alright. Okay. I’ve never read a book by Philip Roth. That’s why this article is not about Philip Roth and should not be taken as an attack on that formerly-alive lion of American letters. I trust that Philip Roth and his fiction are everything the Nobel committee would’ve said they were, if (a) they had managed to award a literature prize at all, and (b) they had decided to award it to Philip Roth before now, a time in which he is alive only previously. No, I, who have not read Philip Roth, do not purport to evaluate the writing of Philip Roth. This article is an evaluation, instead, of the writing of his obituarists.

One lives, of course, for the obituary. And I’ve often asserted that I have but one overarching goal in life: not to die by auto-erotic asphyxiation, which makes you look gross and pitiful just at the pivotal moment when you cease to exist. However, no matter the manner of my passing, my obituaries, if any, will not—as virtually all the tributes to Roth’s genius did—mention masturbating into a hunk of liver. This is because I just will have nothing to do with masturbating into hunks of liver. All the obits managed to get the profoundly truthful and liberating liver-fucking, which represented the dawn of a heroic new era in American letters, into the second or third paragraph. It was, evidently, the achievement for which Philip Roth was best known. This might’ve been one of the original causes of the fact that I have avoided his novels, while reading all the other novels ever published. Sadly, I got stuck much later taking a gang of teenagers to see American Pie.

In general, judging from the obituarists, reading a whole lot of Philip Roth does not, in itself, improve one’s writing. That would be another reason to avoid the novels of Philip Roth, while reading all other novels. Here is Sam Lipsyte, Chairman of the Writing Program at Columbia, writing in The New York Times.

Portnoy’s Complaint is a study in what today, in the wake of the Me Too movement, would get called “toxic masculinity.” The escapades of another of Mr. Roth’s protagonists, Alexander Portnoy—including his liaison with a slab of liver behind a billboard—caused a furor in their time, one that for a long period after seemed rather quaint. But a new raw anger has emerged, one that perhaps puts the entire project of exploring toxic masculinity in a new light.

The rawness of the anger here merges with the rawness of the liver, the toxicity of the masculinity seems to flow into some sort of cirrhosis or hepatitis. “Mr. Roth once described his process this way,” Lipsyte continues. “’I dig a hole and shine my flashlight into it.’ If this is the case, Sabbath’s Theater, the story of a bitter, priapic, lust-wracked puppeteer named Mickey Sabbath, is Mr. Roth’s deepest, darkest hole.”

I’m not sure whether that was indeed Philip Roth’s deepest, darkest hole, but I’m sure Lipsyte has more experience of that than I do. The novel sounds great though. Like the bitter, priapic puppeteer that was his greatest creation, many obituaries pointed out, Roth—though a gentle, good-natured, even beloved man—often vented his spleen.

Times columnist Roger Cohen speculates, “Perhaps Roth timed his exit on Tuesday, at the age of 85, as an admonition to a disoriented nation.” However, Roth lived about seven years longer than the average American man, and died of congestive heart failure. He didn’t immolate himself on the White House lawn as a message to Mike Pence or whatever it may be. Still, as one listened his last gurgle, one might have heard or hallucinated that he emitted an imperative to us all, or at least to Cohen, to shape up and stop being so disoriented, lest you end up producing sentences like this: “He embarked, imagination irrepressible, down every road not taken at the fork.”

There have been many moving tributes to this transcendent, almost holy figure. Xan Brooks, in The Guardian, said that reading I Married a Communist "felt like being flattened by a steamroller.” But perhaps the last afterword can be left to the hitherto alive Philip Roth, defending himself earlier this year from the charge of misogyny in the wake of #MeToo, and also, with characteristic subtlety, against those who would question the centrality of his meat to the history of American literature, and to the American character itself. “I haven’t shunned the hard facts in these fictions of why and how and when tumescent men do what they do.”

Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell.