There’s a particular type of illusion that’s become a degrading trend in our time: we believe the alteration of our expressions and descriptions will alter the things themselves. This is a type of repression so deep that we’re able to speak openly about what we’d deny. We can confront a problem safely only by directing it toward a magical solution. It’s not simply metaphorically true to say that this is the reinvention of alchemy—it’s concretely its reinvention, though without conscious awareness of the fact. As with so many problems today, it’s the return of the repressed.

Whether directed toward bodies, laws, or various intentional but somehow still largely unconscious misreadings of history, 21st-century alchemy rests on the pretense of science and reason (here, too, it unconsciously echoes earlier forms). The ultimate violation of biology, and therefore reality, is filled with pseudo-scientific claims and rationales—comparing unlike species, importing claims from bottom-of-the-barrel social science, etc. And all this in the name of impossible transformations (sex), along with preposterous and meaningless litanies (“gender”).

Redefinitions motivated by ressentiment run the gamut from crime stats to the terms used to describe phenomena such as homelessness (“unhoused” persons are somehow an improvement) or the legal status of persons (illegal immigrant—which is at least accurate and clear—has given way to “undocumented” immigrants, calling to mind the absurd idea that such people have simply misplaced their IDs). Similarly, felonies are downgraded to misdemeanors in a number of our cities, in the bizarre but characteristic hope that the new words will transform the crimes. This hope is also a kind of prayer: as if by reducing crime stats on paper, we’ve reduced crime.

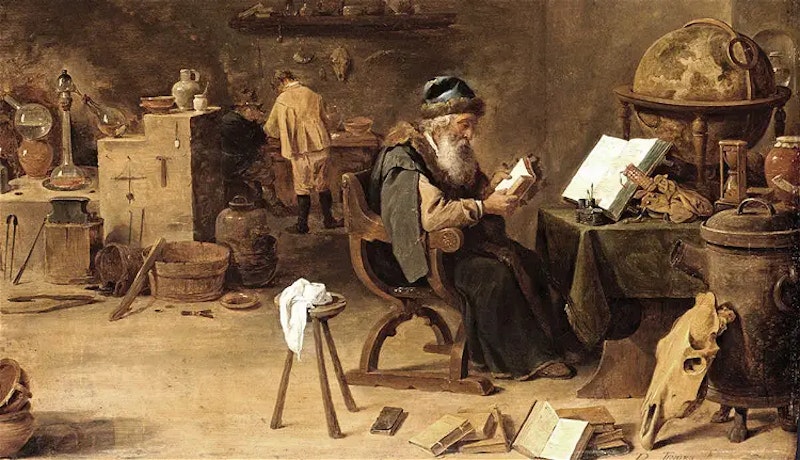

Ben Jonson's masterwork, The Alchemist, is a guide. The play concerns itself with working out the inevitable results of a similarly impossible but tempting pursuit—the manufacture of the so-called philosopher’s stone, an alchemical substance believed to be capable of transmuting base metals into gold and rejuvenating the life and health of its possessor, even offering immortality. Three con men, who never imagine themselves capable of manufacturing this elixir of life, as it was known throughout medieval Europe, allow their targets to believe they’re already on the verge of perfecting it. Their marks are willing to offer money and even the sexual favors of loved ones—anything to get this miraculous elixir.

In the end, greed and gullibility undo them. As we would change things in speaking of them with different terms, here, fools hope to become rich and powerful without effort, simply by bribing an alchemist, or effecting a piety they don’t possess. Believing in the possibility of these dreams in proportion to their appeal, they allow themselves to be taken in and robbed. As long as they’re reassured that the amazing discovery is almost at hand, they prove willing to believe. And temporarily, these illusions hold.

Here’s how one critic summarizes the main action of the play: “Three cozeners agree to rob as many fools as possible… They are thieves, but they throw a specious air of legality over their activities by euphemistic terms, believing in the common fallacy that, if one refers to low things in high words, one raises them legally and aesthetically. In short, Dol, Subtle, and Face speak as though they had set up a commonwealth (‘confederacie’ to Surly [V. iii. 23]), with an instrument and articles, a King and a Queen, and a whole world of subjects.”

Within this tripartite structure, the three cozeners each have a definite function. Subtle passes himself off mainly as an alchemist who’s about to succeed where others have failed—if only his targets are willing to give him precious metals, money, or other coveted goods, he’ll produce the philosopher’s stone. Face, the butler whose master has fled London because of a plague, transforms himself into a kind of jack-of-all-trades, who lures victims into the house, tempts them with promises of gold and women, and facilitates and assists Subtle generally. Dol, a con artist and prostitute, likewise assists where she can, tempting and facilitating in her turn.

The plot of the play, which Coleridge considered among the best in literature, is a straightforward working out of everything the basic situation and characters set up. Each of the would-be beneficiaries of the philosopher’s stone are punished in a way appropriate to their dreams and their characters. Subtle and Dol are sent off without their profit. But Face, having confessed his misdeeds to his returned master, is able to persuade him to join in the deceit for his own benefit. There’s no easy concluding moral. For most of the characters, the dream of wealth is destroyed by the action. When the truth is revealed, they’re ruined. However, for two of the characters, lies are profitable. Jeremy/Face and his master get at least some of what they want by dishonest means.

Back to part of that summary: “believing in the common fallacy that, if one refers to low thing in high words, one raises them legally and aesthetically…” To bring that in line with our own situation, we’d now have to add: metaphysically. Because those who profess a lack of, if not a rejection of, metaphysics, are today our grandest metaphysicians. They’re our alchemists. Though, unlike the confederacie of thieves in Jonson, they lack awareness of their own fraud, as well, therefore, as the enjoyment of cozening—because they’ve first cozened themselves. And it’s this joyless oblivion that finally defines them.

To gull oneself: this is possibly the best definition of today’s alchemy. Lacking awareness of their own fraud, they make themselves lower than run-of-the-mill thieves and charlatans. On the other hand, we can consider the frauds in Jonson’s play who know themselves to be frauds, and who, when things are going their way, delight in that. The worst that happens to Subtle and Dol is that they leave without riches. They know the stakes of the game going in. But their victims, who allow themselves to be taken in because of their greed, vanity, and self-deception, lose a game they aren’t aware they’re playing. These “victims” resemble today’s advocates and pseudo-victims in this above all: their self-oblivion.

But they differ from today’s supposed victims in a key way: their desires are not unnatural, and their motivations are infinitely more understandable. Consider Dapper, a wannabe gambler whose motives are all surface: he wants to win at cards and prosper. Or Drugger, a tobacconist who simply wishes to launch a successful business. Then there’s the hilariously-named Sir Epicure Mammon, who likewise wishes to obtain the philosopher’s stone for the sake of enormous wealth and power.

Even the main motivations of the Puritans, who also seek to profit by alchemy, are, ultimately, greed and vanity. It’s tempting to compare them to today’s new Puritans, and their self-righteous tone makes that comparison more appealing. Still, their baseness prevents us from despising them to the same degree. They’re merely greedy and vain, and all their talk about pure motives and good works are but masks to hide the motivations they share with whores, pimps and thieves.

What all of these men have in common is that their greed and vanity far exceed their sense. The fraudulent alchemist and his assistants suck them in with the promise of transmuting their baseness into gold. In the end, they’re merely robbed of what they came with and sent away with nothing. But greed and vanity are forgivable human weaknesses. The greedy and vain have nothing on true believers and ideologues. When they fail to get what they want, they leave with nothing. Their illusions don’t outlast the possibility of their reward. Unlike us, they know when to give up.

By comparison, with the initially clear distinction between conmen and their victims in The Alchemist, consider our own dull time, in which the former group has receded from view, and the latter has picked up their slack in order to perform various frauds upon themselves. Instead of the philosopher’s stone and riches, what they claim to want is the alchemy of the body—in which various impossible transformations are spoken of as if they’re real; or, fabulous transformations of society. Necessary institutions and structures are removed because they strike immaturity as oppressive or destructive; or various absurd transformations of culture—in which the great works of the mind are dismissed because of irrelevant identity markers, interesting only to children and fools.

It’s true that many of the apparent distinctions mentioned above break down as much in our time as in the play: our unconscious metaphysicians and alchemists aren’t always true believers; sometimes they are closer to joyless versions of Face and Subtle. That is, often enough, they’re after mere gain, and care only about the illusion of spectacular metamorphoses inasmuch as those illusions can be sold as a kind of aery consumer good (think of certain distinguished professors of ressentiment in this connection).

However, even though it’s tempting to assume that such types are consciously selling—that is, to call them cynics—it’s probably true they’re at least half-believers in their strange and impossible merchandise. They never reach the level of self-conscious fraud on which Dol or Subtle can intermittently pride themselves. They’re more fools than rogues. And it’s for this reason that we feel such contempt when we see them, read their painful theories, or hear them speak. We can abide a rake, even a common prostitute; but asking us to extend any brotherly affection toward an ideologue… well, just how gullible would we have to be?