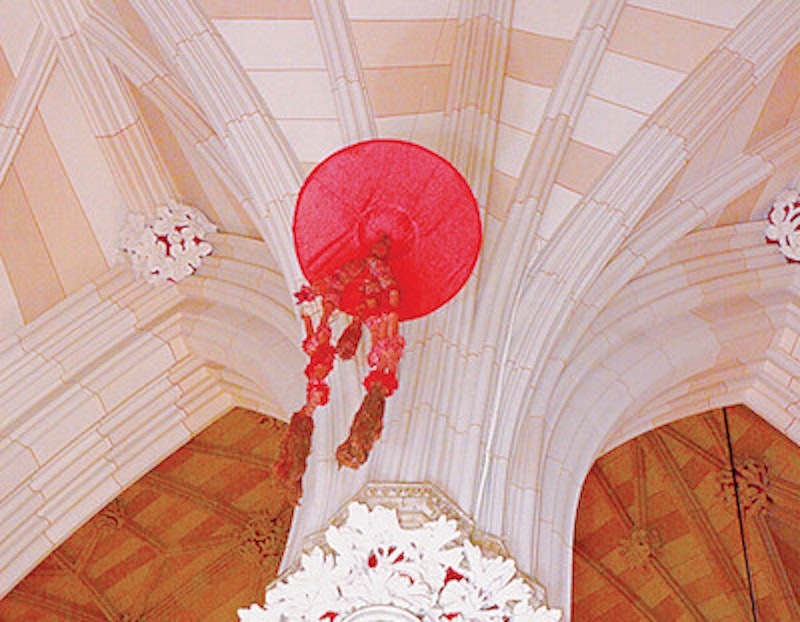

The red hats hang from the ceiling of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, high above the sanctuary. Each galero—a circular, broad-brimmed hat, ornamented with thirty tassels of scarlet thread interwoven with gold, 15 to a side—denotes that the cardinal who possessed it had once possessed the Cathedral, and held jurisdiction over the Catholic people of New York.

In the old days, he would’ve received it from the hands of the Pope. The new cardinal, vested with a scarlet watered-silk cappa magna, the great cape worn by cardinals for 1000 years, was led to the Sistine Chapel. He reverenced the Divine Presence on the altar and the enthroned Pope.

At this point, as Peter C. Van Lierde wrote in his 1964 book, What is a Cardinal?: “After kissing the Pontiff’s hands and cheek… the Cardinals-elect prostrated themselves on the floor before the altar while the Pope read prayers over them. Then… the Pope recited in Latin: ‘To the praise of Almighty God and the honor of His Holy See, receive the red hat, the distinctive sign of the Cardinal’s dignity, by which is meant that even unto death and the shedding of your blood you will show yourself courageous for the exaltation of our Holy Father, for the peace and outlet of Christian people, and for the augmentation of the Holy Roman Church. In the name of the Father and of the Son and the Holy Ghost.’”

Then the galero was then presented to the new cardinal. He never wore it again. Later, it would be carried before his coffin, then placed at the foot of his bier, and finally hung from the ceiling of his cathedral.

Eight of the 10 archbishops of New York have been cardinals: John McCloskey, John Farley, Patrick Hayes, Francis Spellman, Francis Cooke, John O’Connor, Edward Egan, and Timothy Dolan. If the first archbishop, John Hughes, the charming, eloquent, self-educated, adamantine “Dagger John,” as obnoxious to the Establishment of his day as Al Sharpton once was to ours, had lived a little longer, one imagines Pius IX would have granted him the red hat.

Michael Augustine Corrigan, the third archbishop, also did not receive the hat. He reigned from 1885 until 1902. An honest, hard-working, competent administrator, His Excellency lacked finesse in political relations.

One imagines Leo XIII was unimpressed when Corrigan excommunicated one of his own priests, Father Edward McGlynn, over reasons rooted in politics. McGlynn was a radical firebrand with a hob-lawyer’s genius for remaining just this side of canon law. During the New York City mayoral campaign of 1886, Corrigan forbade him to speak in support of the United Labor candidate, Henry George. Nonetheless, on at least one occasion McGlynn appeared on George’s platform without speaking, having first ensured that all present knew Corrigan had silenced him. It was merely one of McGlynn’s many provocations. When Corrigan rose to the bait and not only suspended McGlynn’s faculties as a priest but excommunicated him, bell, book, and candle, McGlynn appealed to Rome. Then as now, Rome takes its time in these matters. Six years later, in 1892, Rome ordered McGlynn’s reinstatement. Corrigan was utterly humiliated. Nonetheless, he obeyed Rome as he had expected McGlynn to obey him, without delay or reservation.

•••

To describe a cardinal as a prince of the Church merely states a fact. We sometimes forget that the Popes wielded temporal power until 1870, when Vittorio Emmanuele II completed the unification of Italy by the seizure of Rome. Both the Congress of Vienna and the Congress of Berlin confirmed, and the Treaty of Versailles in 1918 ratified, that membership in the Sacred College of Cardinals carried with it diplomatic status equal to that of princes of the blood royal. As such, cardinals took official precedence behind emperors, kings, and their immediate heirs, or a head of state. No other person ever outranks a cardinal. Since at least the 17thcentury, all cardinals have enjoyed the title and dignity of “Eminence.” Thus, in conversation, he is addressed as “Your Eminence;” in formal communications, he is addressed as Most Eminent Lord or Most Eminent Cardinal.

Today, precedence is generally a question of protocol, the rules governing the political and social relationships of nations and the people who represent them. As with all codes of etiquette, protocol creates a sense of order in both the ceremonial and the mundane. It is considerably more than the question of the rank of the person receiving a cardinal at the airport, the number of troops in the honor guard, or the number of salvoes in an artillery salute. Nonetheless, many cardinals, particularly the Americans, find their princely status uncomfortable. One might think that such a thing was in itself a kind of ostentatious false humility—another manifestation of the capital sin of pride by seeking to substitute one’s uninformed emotional response for the measured judgment of the centuries—but perhaps one is mistaken.

These thoughts were prompted while recalling a garrulous Catholic lawyer acquaintance recount his observations of one of John Cardinal O’Connor’s several funeral Masses. The Cardinal died on a Wednesday around eight p.m. By Friday evening, dressed in full canonicals, he was lying in state at the Cathedral. As His Eminence had promised, the coffin bore a union label. My friend was also in attendance, wearing a white mantle and black velvet beret, the ceremonial regalia of a Knight of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem. He was only one of several hundred colorfully dressed persons: the congregation included black-robed Knights of Malta; Franciscan monks in roped, gray robes and sandals; bishops in violet; monsignors in black cassocks piped in red; Capuchins in brown; Dominicans in white; and nuns of several orders in their habits. This was a pale reflection of the exotic and flamboyant presences at Francis Cardinal Spellman's funeral over 50 years ago. Vatican II and the blanding of the Church in America had not begun to take effect (Spellman had sworn to stop the reforms at the water's edge and unlike Canute had held back the tide during his lifetime). Then, the Knights of Malta wore red tunics with epaulettes and cocked hats with ostrich plumes. The Knights of the Holy Sepulchre wore white tailcoats “with collar, cuffs, and breast facings of black velvet with gold embroideries, epaulettes of twisted gold cord, white trousers with gold side stripes, a sword, and a plumed cocked hat.”

My friend received this honor some 20 years ago for reasons as mysterious to him as to me. This is the kind of distinction for which one doesn’t apply. One must be invited. An acquaintance surprised him by quietly asking whether he would accept a Papal knighthood. “I was restrained in my enthusiasm,” my friend said. “I waited three whole seconds before saying ‘Yes’.” We celebrated his knighthood with a symposium in a local watering hole. After all, symposium comes from the Greek for “drinking party.”

The Holy Sepulchre is among the last surviving Crusader orders of knighthood. It’s probably at least a thousand years old: some historians claimed with more enthusiasm than documentation that the Order might’ve existed in one form or another before the end of the First Century of the Christian era. With the fall of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Order gradually came under the protection of the Roman Church.

At one time, its knights enjoyed many privileges,

…some of which were of a rather peculiar character. They had precedence over members of all orders of knighthood, except those of the Golden Fleece. They could create notaries public or change a name given in baptism; they were empowered to pardon prisoners whom they happened to meet while the prisoners were on their way to the scaffold…

They also had the privilege of legitimizing bastards. In America, this notion may need reviving: a look at Washington, D.C. and most state capitals suggests there’s much work to do.

The Holy Sepulchre was among the first orders of knighthood to admit women: its tradition holds that women were knighted for uncommon valor at the Battle of Tortosa in 1149. In the modern era, women were received into the Order as early as 1871.

Regrettably, there are no records of the first American knights of the Holy Sepulchre. One might reasonably speculate they were immigrants who had served in the Papal armies and received one honor or another.

For example, Myles Keogh, a man who rejoiced to go in harm’s way, fought against Garibaldi’s forces at Ancona with the Pontifical Battalion of St. Patrick in 1859 and was knighted in the Order of St. Gregory the Great by Pius IX for valor. During the American Civil War, he fought for the Union and brevetted a Lieutenant Colonel of Volunteers. After the War, he was commissioned a Captain in the Regular Army and assigned to the Seventh Cavalry, where he commanded Company I. He died with his men at the Little Big Horn. Unlike most of the dead cavalrymen, his body was not mutilated: he’d worn the Order’s insignia on a chain around his neck and the Sioux apparently honored it as a symbol of “powerful medicine.” His charger Comanche survived its seven bullet wounds and served the Seventh Cavalry as its mascot until he died at 29 in 1891.

The existence of the Equestrian Order and of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta in this country is a vestige of the temporal power of the Popes. They were sovereigns as well as churchmen. They granted not merely decorations but titles of nobility, and not merely to Europeans but to Americans.

Thus, Nicholas Frederic Brady, an early 20th-century utility magnate and philanthropist, was created a Duke ad personam (non-hereditary) by Pius XI. The descendants of Edward Hearn, a self-made businessman, fundraiser, philanthropist, and activist, may still use the title of Count.

If one enters Fordham Law School, a large bronze wall plaque lists the benefactors whose generosity enabled the construction of the Lincoln Center campus of the Jesuit University of New York. Among them is George, Marquis MacDonald. If memory serves, he’d begun as a contractor, became a spectacularly successful financier, and then a benefactor of the Church. He’d married a daughter of Detective Inspector Thomas Byrnes, N.Y.P.D., who used torture in interviewing suspects (a method once famed as the “third degree”), was fired for corruption by Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, and whose personal fortune came from sources best not examined too closely.

MacDonald became a Knight of Malta, a Knight Grand Cross of the Holy Sepulchre, a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Gregory the Great, the holder of numberless honorary doctorates, and, much to his pleasure, a Papal marquis. To be pedantic, the title is formally rendered in Italian as marchese, but no one was prepared to argue about it with him. He took himself rather seriously. He loved to have his picture taken in the uniform of one or another of these orders. The newspaper photographers loved him, and as his appearance was distinguished, he usually looked like an old-fashioned diplomat or an admiral of the fleet.

Roger Peyrefitte, a French diplomat turned man of letters, wrote The Knights of Malta and The Keys of St. Peter, two romans à clef gently satirizing the Papacy during the reign of Pius XII. Well-written and witty, the novels mixed fact and fiction with enough of the former to irritate the Vatican bureaucracy. Thus, the latter novel was seized by the Italian police. In The Knights of Malta, the Marquis MacDonald is portrayed as “a sort of human mastodon wearing a ten-gallon hat and with an enormous cigar sticking out of one corner of his mouth.” His conversation with the Holy Father resembles that once-famous American woman convert who talked to the Pope “of Catholicism with so much authority, so much force and warmth, that His Holiness was obliged to remind her, gently, that he, too, was a Catholic.”

Titles, decorations, uniforms: these things have a certain romantic charm. But even my old lawyer friend noticed the important thing. During the Order’s ceremonies, the reading that most moved him came from Ecclesiastes:

Remember your Creator in the days of your youth, before the evil days come

And the years approach of which you will say, I have no pleasure in them…

Before the silver cord is snapped and the golden bowl is broken,

And the pitcher is shattered at the spring, and the broken pulley falls into the well,

And the dust returns to the earth as it once was,

And the life breath returns to God who gave it.

Vanity of vanities, saith the prophet,

All is vanity.