In my 20s, I tried to be a poet. Every morning, I’d wake up at 4:30 and write for a couple of hours before going off to my day job. Every week, I printed out the product of my labor, folded it up, and sent it off to a range of poetry magazines with semi-witty, inoffensive names like Interim, Something Review, Words Quarterly or Review Quarterly Review. Eventually my returned stamped envelope would come back with a little note saying, politely, that I sucked and was wasting their time. Then I’d send the poems off somewhere else (perhaps to Quarterly Review Quarterly) and wait for further news of my failure and general inferiority.

I did this for years. And then, eventually, I got the message. No one in general wants to read poetry, especially not mine. I stopped getting up early. I stopped writing poetry. I mostly stopped reading poetry. And I swore that I wouldn’t submit to Something Words Southeast Review Quarterly ever again. Months turned into years, years turned into decades, and I kept my vow. I failed at many things, and my writing was rejected from many places, but I didn’t write poetry and wasn’t rejected by poetry magazines. Whatever else was wrong in the world, that at least was right.

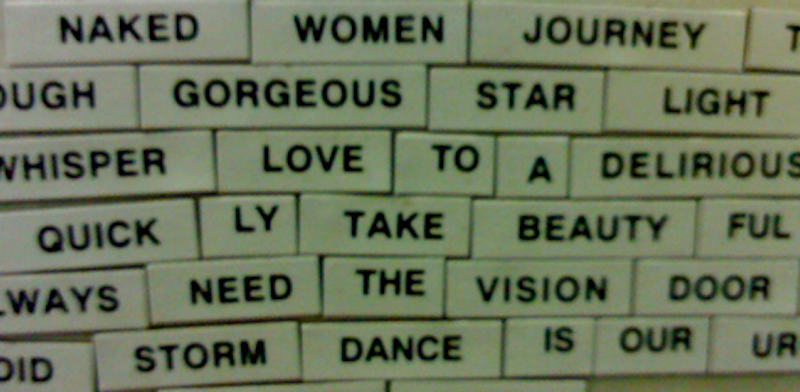

But then, slowly, like a really foolish person, I started writing poetry again. First in dribs and drabs—a short poem about our beloved deceased greyhound here, a cat haiku there (If you put your nose/In water, it will get wet./Now the cat is sad.) Then this December the dumb, damn dam burst, and poems sluiced through. There were sonnets, villanelles, lyrics, free-verse effusions, Joe Rogan transcript collage pantoums. There were poems in prose, just like a real poet. It was fun. I write much faster now, because I’ve practiced writing 1000 words a day as a freelancer for 20 years. Also because my standards have been significantly lowered now that I know everyone hates my poetry so there’s no reason to worry about whether it’s good or not.

All was well. And then, I thought I’d like to publish some of this. Because I’m a dope. Since my day of sad stamps and sad SASE, the poetry submission process has largely moved out of the post office and onto email and platforms like Submittable. Everything is streamlined. Including the humiliation.

The poetry publication process is still filled with contests where you can pay $10-$20 so judges can give some other, better poet a cash prize. But even free submissions now come with innovative pay-to-play options. Most magazines have a two- to three-month turnaround time—but also offer an option where you can pay them to reject you, ahem, review your submission, more quickly. Many magazines also offer to provide feedback. For $50-$60 they’ll tell you why they rejected you and explain why you should give up poetry for a less soul-crushing avocation, like cleaning toilets.

Poets like to say poetry is an alternative to the grim utilitarian neoliberal calculus of capitalism. (“Both Bufton and Alizadeh identify the hollowing out of language as a key component to capitalistic dominance whether through jargon as elitist gatekeeping or sexism in-built to corporate culture,” etc.

Poetry is useless, uncommercial, fresh, individual. You trapped in that gray office grinding out memos with earning statements—don’t you wish you could be a poet too?

Everyone wants to be a poet. And when there’s high demand and low supply, it’s easy to gouge. Poetry institutions work like petty corporate scams, complete with the rhetoric of can-do corporate uplift.

All these desperate people want to be recognized for their perfect individual suchness; they want to be celebrated spiritual entrepreneurs. So they throw money at the screen, investing in themselves and their non-existent futures. Then the slightly more established, slightly more successful people on the other end will tell them, “No, actually, you suck. But keep trying!” It’s like playing the lottery, except if you win, you get to speak into the void, and if you lose, you speak into the void, but with more self-loathing.

I’ve taken a vow to never pay to have my poetry read—but given my success at keeping other poetry vows, I don’t know. It’s easy to see that one is engaging in unhealthy behavior, but harder to stop. I too dream of being a celebrated spiritual entrepreneur, and having some critic enthuse about how my inimitable imagery makes the familiar strange, or perhaps just more familiar.

It’s been fun remembering how much I love writing and reading poetry. It’s been less fun remembering how easy it is for ambition, hope and capitalism to turn all the things you love into a source of drudgery and degradation.