Years ago my father worked as a corporate speechwriter. He was a very nervous man and the job was agony for him. But the agony was for a peculiar reason. He told me about it one time when we were driving and I asked about his life.

The job was his second or third out of college, my father said. He was a good writer: His cover letters had gone over well, including with his new employer. And recently he had learned to enjoy the great classics he'd been making himself read—he felt happy when alone with their prose (my words, not his, but they sum things up). My father felt very close to language, like they were friends.

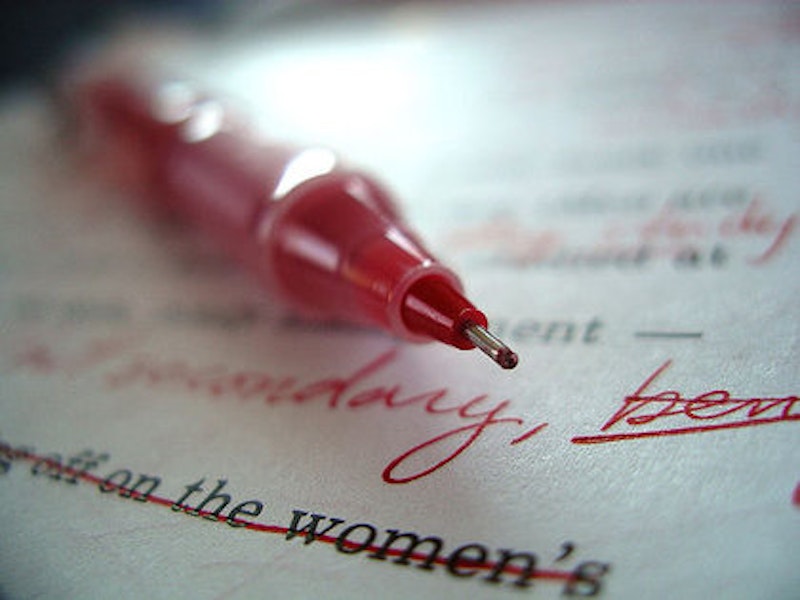

His boss at the new place was about 50 or so, a weathered man with rust-orange strips of hair laid across his brow. He had come up through state college, not the Ivy League, though my father said he never seemed to bear a grudge for that. When I pressed, my father said he and his old boss were always on good enough terms, right to the end. But the boss would go through one of my father's drafts and strike here and there with his red pen. He x'd out half a sentence and wrote two words. Or he x'd a third of a paragraph, say. But that was rare, and the smaller xing's amounted to just two or three goes per draft.

Did the changes make sense? My father's lips pressed, he slumped and considered the road ahead. The jottings had been hard to read, he said. The cuts... sure, the cuts mainly made sense. Sometimes you could go one way or the other. Looking back, my father said, he believed that the boss in question, Ed, he just knew the rules for good writing and, damn it, he was going to use them.

Everything else about the job was proceeding well enough. People talked to my father in the hallways. The speeches he wrote were considered to hit the mark. And so on. He was succeeding, really—not the term he used when we talked, but I think that's what it came down to. On your second or third job out of college, you really want people to be glad you're there; otherwise your life is losing some serious traction.

But the job didn't work out for my father. He left after a year and a half. He started writing badly, is what it came down to. Sometimes he was writing too little and turning in meager drafts just before deadline. Sometimes he was writing prose that twisted around, unable to say what it meant. People didn't like what he was doing anymore.

Ed and my father had their regretful, and brief, last interview, and Ed sent my father to find his way in the world, a young man of almost 30 who couldn't do what he was supposed to do.

My father never explained what it was about the x's that did him in. He was sensitive and delicate, but even for someone like him they seem like a very small blow. My guess is that the x's hit a particular nerve point.

I can imagine my father going back to his office, circling the x'd out bits in the draft, circling them again, telling himself there was his target right there, he just had to get to work on that, and then finding he couldn't. He'd peer at the sections, look at them one way or another. He'd know what was in them, but he wouldn't be able to think about them. His mind would shrink from the subject.

This block, this area of difficulty, would become his chief preoccupation when he sat down to write. Everything else had been taken care of, he thought somewhere deep in his head. It was just the sentences that triggered the x's. If he could avoid whatever triggered the x's, then he'd be doing what he was supposed to, absolutely and perfectly what he was supposed to. But, for whatever reason, he could never be good. I won't get into that, because it's a tangle: whether he felt that being good was giving in, or whether he thought he didn't deserve it, or both. But that was the set-up of his mind, and his life was shaped accordingly. In this case he flunked out of a job.

As I see it, my father wrote by holding himself to rules, and mentally he did this the way a child does: Follow the rule because otherwise you are bad. Lots of people do that, I think, but maybe he took it more seriously than most.

At any rate, the red x's did him in. They were there to say he had done wrong, and he danced around them until he ran out of energy. That was his life in the late 20s: sitting at his desk, thinking of the young wife and the child he'd soon have to support, trying to guess the slant of a t or an i so he could figure out what his boss had written. Feeling like everything had to fall away from beneath his fingers, that the cliff face was getting loose.

I forget what I asked him that caused this story to come up. I was in my 20s, like he had been, but my job was going okay. I suppose I felt like we were both aimless and adrift, no matter what our job status, and somehow that led to the topic.

The story's happy ending is that after the debacle my father was able to write again—cover letters, for the most part, but fine cover letters. And he still read. Really, he was designed by nature—his brain, his nerves, his temperament—to produce smooth, well-tempered prose that said what somebody else wanted to say. But like most things it didn't work out.

I never told my father any of this, of course.