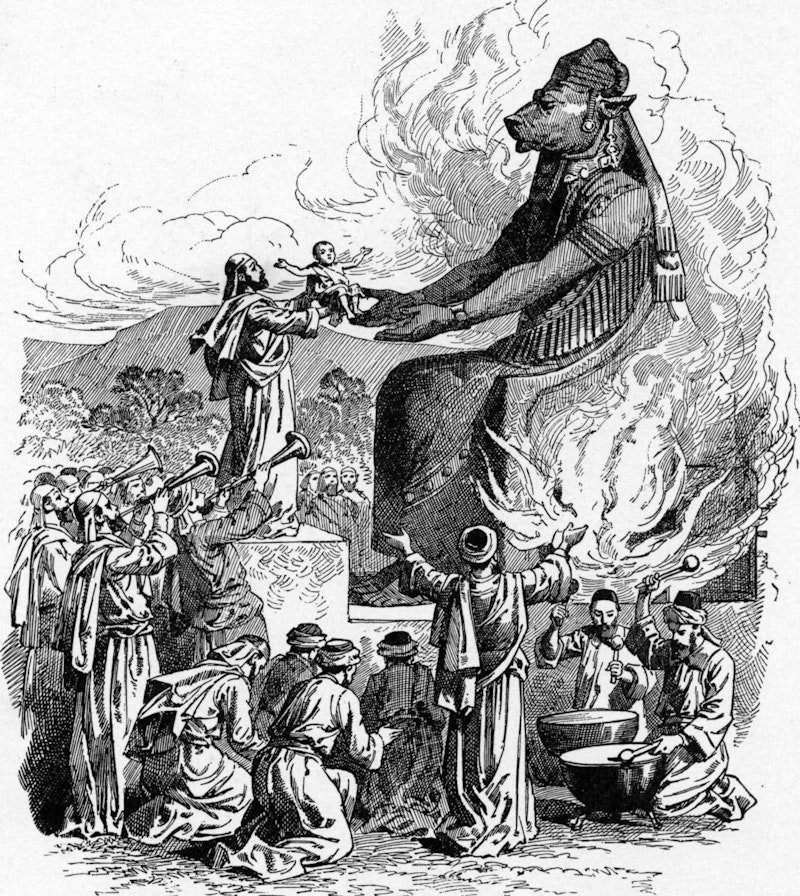

Moloch, also spelled Molech or Molek, was a deity worshipped in the ancient world by the Canaanites or the Carthaginians (scholarly accounts vary) and associated with child sacrifice. It’s often portrayed as a bull-headed idol over a sacrificial fire. I’d given little thought to this entity until I came across a Rod Dreher column in The American Conservative from last November. Dreher drew upon The Return of the Gods, a bestselling book by New Jersey-based Messianic Jewish pastor Jonathan Cahn that identifies ancient deities—demons, actually—as making a comeback amid declining Judeo-Christian faith. Among them was a “Dark Trinity” of Baal, Ishtar and Moloch.

In March, shortly before his column was terminated, Dreher praised feminist author Naomi Wolf for a receptive essay on Cahn’s thesis. Wolf wrote that Cahn had “accurately traced the lineage of pagan worship and pagan forces” and that “these negative but potentially powerful forces have been dormant for two millennia [but] have now taken this opportunity, of our turning away from God, and they have returned.” This includes the “sheer amoral power of Baal, the destructive force of Moloch, the unrestrained seductiveness and sexual licentiousness of Astarte or Ashera.” Wolf noted that “while it would be easy to dismiss Pastor Cahn’s theory as wacky and fanatical, I have reluctantly come to believe that his central premise may be right.”

References to Moloch have increased on the American right. Last September, Steve Bannon, holding up a New York Times photo of Independence Hall bathed in red light as backdrop for a speech by President Biden, explained that this was a celebration of crime and chaos in Philadelphia. “That’s Moloch,” Bannon said. “They did that on purpose.” In November, Donald Trump “retruthed” a user’s post on his Truth Social platform that praised his public service and included among his motivations, “Perhaps he could not stomach the thought of mass murders occurring to satisfy Moloch.”

As I’ve noted previously, the view that literal demons constitute or control one’s political opponents is a pernicious belief that fosters ruthless, unhinged behavior. Still, demons hold a fascination, familiar in literature and fantasy but also extending even to rationalistic precincts of science and philosophy. Historian Jimena Canales, author of Bedeviled: A Shadow History of Demons in Science, has delved into how summoning imagined entities such as Maxwell’s Demon (an entity that might reverse time or violate the laws of thermodynamics) has generated insights into how the universe works. Such demons have also appeared in computer science, as metaphors for complex processes.

Similarly, Moloch has emerged as a personification of destructive competition, or negative-sum games, in which participants suffer while trying to keep ahead of rivals. This conception, put forward by blogger Scott Alexander in a 2014 post, draws upon such cultural depictions of Moloch as Allen Ginsberg’s mid-1950s poem “Howl,” which evoked a “sphinx of cement and aluminum” that “bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination”; and the 1927 film classic Metropolis, in which an underground machine staffed by frenzied workers becomes the fiery-mouthed demon.

Liv Boeree, a science communicator and former pro poker player, has amplified the Moloch metaphor through clever videos. In one, Boeree depicts the “beauty wars” as an example of such negative competition. An attractive woman, she notes that her social-media posts got greater attention if they included alluring pictures of herself; and that she and others had an incentive to constantly upgrade their looks, including through aesthetic filters on Instagram, creating a cycle of unrealistic expectations.

I watched this video intently, especially the parts where Boeree appears as a scantily-clad Moloch, wearing horns and espousing a zero-sum philosophy in a steamy milieu of red candles and dripping wax; cackling mirthfully and staring intimately at the camera with red-hued eyes; rubbing a peacock feather across her face or sticking out her tongue for a caress from one of her long fingernails. At other points, Boeree appears with no make-up or filters, and looks quite nice. But it’s her Moloch one wants to serve.

—Kenneth Silber is author of In DeWitt’s Footsteps: Seeing History on the Erie Canal and posts at Post.News.