Joanne B. Freeman starts the introduction to her recent book Field of Blood with Charles Dickens’ visit to Washington, D.C., and his recollection of the United States House of Representatives. He mocked its mucky floor coated in brown spit and used chewing tobacco, and for Freeman that image serves as a metaphor for the legislature of the time: “The antebellum Congress had its admirable moments,” she says, “but it wasn’t an assembly of demigods. It was a human institution with very human failings.”

This is true, but I wonder how many other countries need to be specifically told not to imagine its 19th-century legislators as “a lofty pantheon of Great Men.” Especially in a book about the personal violence they inflicted on each other.

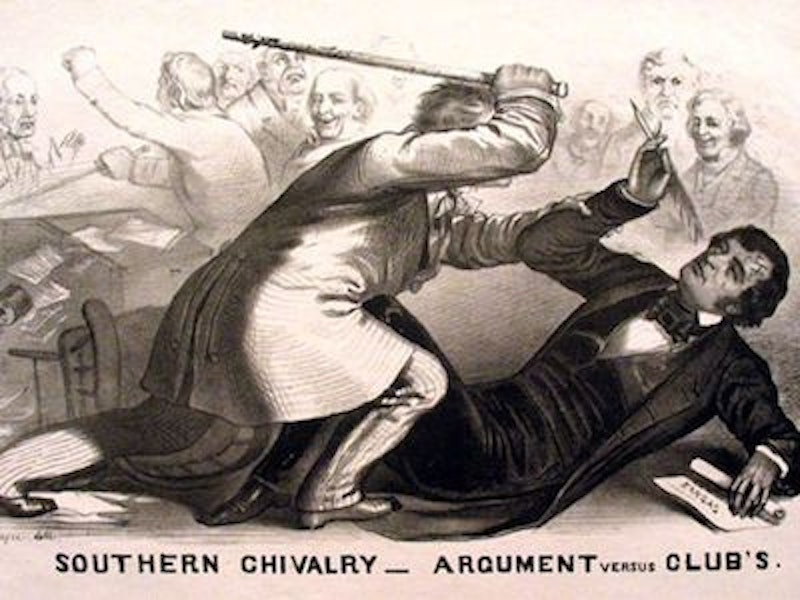

Freeman’s history is about the brawls and beatings that took place among Congressmen between about 1830 and the outbreak of the Civil War. During this time the House in particular saw knives, canings, and gunshots. Duels were fought, and men died. Freeman contends, convincingly, that this shaped political discourse. She follows Benjamin Brown French, a House Clerk originally from New Hampshire who had a knack for being in the near vicinity when major historical events were happening; present when the Gettysburg address was delivered, he also sat with Mary Lincoln immediately after her husband was shot. His diary’s a key primary source for Freeman, who must reconstruct Congressional confrontations that were left discreetly unrecorded in newspapers and official records.

French’s recollections are accompanied by letters and diaries from other men who witnessed or were involved with the events of the time. Freeman’s writing gives these sources new life, and she has a useful section describing Washington, D.C. in the 1830s, a small but booming city marked by grandiose government buildings and a surplus of bars. There’s an appropriate concern with the physicality of place: the overcrowded House floor with its tobacco-stained floor, the smaller halls and parlors where committees met and private talks were had.

The Field of Blood is well-written, though I didn’t notice an explanation of the title reference (in the Bible Akeldama, Aramaic for “field of blood,” was the name given to a field bought with the 30 pieces of silver Judas got for betraying Christ). Freeman has the benefit of dealing with inherently dramatic themes—power politics and physical conflict—but given the untidiness of history dramatic tension can only carry the book for short stretches. An early chapter’s structured around an 1838 duel, for example, but the point is that the narrative of the duel fits into an overall pattern. Freeman’s strength here lies in how she unifies her material, establishing themes and finding a development over time in how violence manifested.

The book perhaps overstates a sense of Congress as a near-sacred space, but otherwise Freeman finds a balance between respecting the people she writes about and having perspective on their words and actions. Her concern with freedom of speech, and how the threat of violence was used consciously to suppress certain political perspectives, is thoughtful.

So why was that generation of Congress so violent? Some of it might’ve had to do with the easy access to alcohol; inside the Capitol building alone were two bars, a refectory, and Daniel Webster’s private wine room. Given that most of the Congress were, inevitably, out-of-towners whose real homes were among their constituents, and how much of the population were temporary residents for a term or two, one has the impression of Washington as an ongoing convention or cruise ship: a place that isn’t home, where typical behavior can be thrown off.

But that’s not the main story. Freeman’s chronicles how much of the violence came from Southern men. Southerners had an honor code with detailed formalities around dueling, at this time reviled in the North. They also had a culture shaped by the brutality inherent in slavery. Violence was a part of their lives, and they brought it with them from the plantation to the Capitol.

Many of these men faced criticism of the institution of slavery for the first time in Washington, and often didn’t handle it well. They threatened and attacked Northerners, many of whom were avowed noncombatants. Violence, and challenges to their opponents’ manhood, became part of an arsenal of tactics Southerners used to preserve slavery, along with parliamentary regulations like gag rules and procedural complaints.

Northerners were often desperate to maintain the Union and were reluctant to meet threats with threats, force with force. The institution of political parties, national organizations that included both Northerners and Southerners, emphasized the need for politicians from different parts of the country to deal with each other. It was the emergence of the Republican Party, Northerners who were prepared to fight, that changed things—leading to, among other events, a mass brawl on the House floor in which one honorable member went to grab another honorable member by the hair and found himself clutching a toupee.

Freeman describes her sources and how she was able to find details about the violence in Congress. These details weren’t written up in the official record of debates, and the most frequent bullies would lean on the press to get them to refrain from reporting on the fights. This met with limited success—threatened editors would often respond by not writing about the Congressional bully or bullies at all; then as now, publicity was air and nourishment for politicians.

Still, much was hidden. What is perhaps most intriguing in a highly intriguing book is Freeman’s description of how she came to recognize when a physical altercation was covered up in an official text. When words and speeches were precisely recorded, a certain pattern of interjections and responses often hinted at a physical conflict that could be uncovered by reading diaries and letters of observers. Hidden violence, she found, has its patterns. Her book shows it’s best to bring them what’s hidden out into the open; to see, in this case, how the violence of a slave-owning culture spilled over to other forums.