Within the pantheon of Jack Kirby creations Kamandi stands as the most dystopian, misanthropic, and sentimental of all. The writer/artist debuted the character in 1972 in DC Comics’ Kamandi The Last Boy On Earth no. 1. From there Kirby helmed the series for 40 issues that took post-apocalyptic sci-fi into strange new places that few doomsday prophets had ever considered. Eschewing the common downtrodden tone, Kirby’s Kamandi is a fable-like epic of survival and rebirth that’s as hopeful and absurd as it is shocking and poignant.

As a World War II veteran who grew up during The Great Depression, Kirby’s lifetime was engulfed by political and cultural upheaval. His successful comic book career spanned the 1940s, 50s, 60s, and 70s. A self-taught artist uninterested in formalism, he developed a style of visual storytelling that made him a pioneering figure in the history of romance comics. In the early-1960s Kirby became one of superhero comics’ leading creators. As society became progressively more bloated and self-centered, Kirby’s 1970s work (especially his Fourth World franchise) reflected a more diverse understanding of heroism and villainy.

The economic prosperity brought about by the post-War era spawned a false sense of security which in turn fostered the dangerous belief that the sanctity of peace didn’t need constant preservation. The conflicts of Korea and Vietnam proved that military police actions could be central in shallow culture wars and economic exploitation. Non-violence was written off as a disposable dream while toxic masculinity and needless sacrifice became ways of life for the Cold War’s masterminds, defense contractors, and other corrupt political entities.

In Kirby’s imagination, the next logical step was de-evolution. That de-evolution gained an imaginary identity as Earth A.D. (“A.D.” in this case meant “After Disaster”); this was the setting in each Kirby-created Kamandi issue. The scruffy/perpetually disoriented teen Kamandi embodied the feelings of alienation and disenfranchisement that dogged the hippie movement as its Aquarian dreams were trampled by the raging consumerism of the “Me Decade.”

The Last Boy On Earth was born and raised in some unknown era of the distant future in an expansive fallout shelter tricked out with a vast emergency food supply, comfortable living quarters, and a cavernous/internet-esque library of reference media, most of which documented the history of the 20th century. This ironclad bunker was one of many built throughout North America to protect civilians from the dangers of atomic war. The shelter was named Command “D”; Kamandi’s parents chose to phonetically name him after his birthplace. It was a tribute to the last refuge from mass destruction that the family enjoyed together. The boy’s mother and father perished soon after his birth just as most of human society wiped itself out in a doomsday holocaust called The Great Disaster.

Several years later Kamandi becomes the only life form on Earth AD unaffected by radioactive mutation. The tension between his freakish “normality” and the mutant-dominated society is at the center of most Kamandi narratives. These usually fell into three distinct categories: tragic melodramas eulogizing the beauty of culture and society before The Great Disaster; character studies focusing on the emotional and psychological wounds of war and violence; high adventure tales that combine the swashbuckling of Edgar Rice Burroughs and Jules Verne with the nascent post-apocalyptic aesthetic that would soon define Escape From New York, the Mad Max franchise, and other nuked-out sci-fi classics.

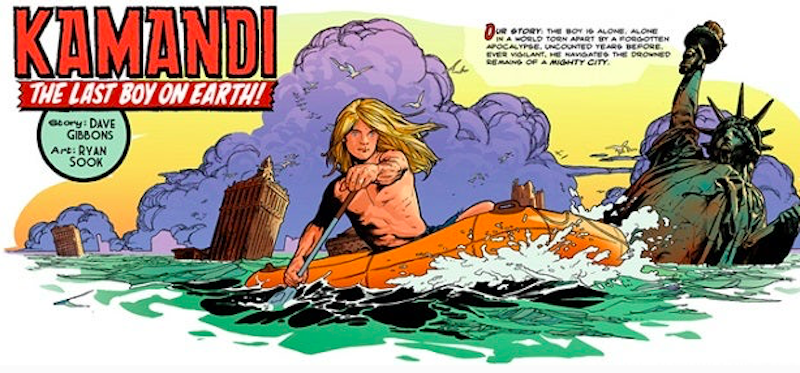

The first issue of Kamandi The Last Boy On Earth is a stunning prediction of the series’ dramatic highs and lows. The protagonist returns to his bunker from a perilous reconnaissance mission in the flooded ruinous canyons of NYC only to find that his grandfather (Buddy Blank) was murdered. The boy is preyed upon by fearsome humanoid tigers, leopards, and wolves. These highly intelligent anthropomorphs and a diverse menagerie of other mutants become Kamandi’s deadliest enemies. Conversely, Kamandi’s genetic human relatives re-emerge on Earth A.D. in a brain damaged/primal state. The mutants treat these animalistic humans no better than pets or livestock. Kamandi witnesses his furry opponents’ rigid codes of military honor, their aggressive speciesism, and a strange ritual where an ancient/phallic warhead becomes a religious idol. Through all of this mayhem, he displays a resilience that doesn’t come from any militant stance or political ideology. As the last of his race, Kamandi’s survival is the one thing that can insure humanity’s return to pre-Disaster glory.