I am a 14-year-old sadist. An eighth-grade Jeffrey Dahmer. Or at least that’s what Mr. Shawn tells me. The guidance counselor, Mrs. Merwin, is much nicer. She says that teens are fascinated by violence and that my behavior is not uncommon. What we need to work on—everything is “we” with her—is channeling that interest into something more productive. Sports, maybe? These people think I’m attracted to violence, but I’m not. Humor is what motivates me. I invented The Kool-Aid Game because I thought it’d be funny, not because I needed to release some pent up aggression. Basketball? That’s not funny. Staging an elaborate scavenger hunt that encourages violence, betrayal, and dishonesty? Hilarious.

Mrs. Merwin’s room is conspicuously comfortable. The walls are a pastel green which is probably supposed to convey “serenity and reassurance.” Toys—Slinkies, stress balls, that box of pins that fits to the contours of your hand—are scattered throughout the room. She encourages me to play with them as we talk. I’m sitting in a beanbag chair, for Christ’s sake. This lady is trying too hard.

I didn’t even know we had a guidance counselor. I feel like Matthew Broderick’s character in War Games, like I had just accomplished something well beyond my years. My precociousness should cancel out the bad behavior.

“Now Booker,” Mrs. Merwin says. “Let’s lay it all on table. Get all the information out there. Remember, this is a safe space.” She speaks softly but with confidence. I can tell she’s being honest. She’s probably a great mom.

I want to brag. “What do you wanna know?” She’s surprised by my willingness to talk. She takes a minute to mentally sort through her stable of questions, carefully deciding which to ask first. She finally settles on one: “What does ‘Red Kool-Aid’ mean?”

“What do you mean ‘what does it mean?’”

“What is it slang for? Is it a drug? You can tell me if it’s a drug.”

I squint to illustrate how stupid her question is. Grownups, man. They’re so paranoid. “It’s red Kool-Aid, Mrs. Merwin. Like, y’ know, Kool-Aid in a plastic bottle. You can buy it at 7-11.”

“Oh! That’s good! Good, good. Okay, so… there was a little disagreement over the Kool-Aid?”

“You could call it that… I mean, everyone just wanted to win.”

“Win what?”

“The Kool-Aid game,” I say. And then I explain the rules. She doesn’t quite follow along. I think I’m the only one who fully comprehends the genius of my game, if you can even call it that.

“Quite the imagination,” she says when I finish talking. “Glad we cleared this up. I’ll talk to Mr. Shawn, give him the scoop. I see no reason why you should get in trouble for this… we’ll call it a misunderstanding. Just apologize to Zach and everything will be fine.”

I’m disappointed that she doesn’t recognize my brilliance. Anyone who did would’ve suspended me at the very least.

“The what?” Peter says.

“The Kool-Aid game,” I say to the five contestants. We’re in the eighth-grade lounge. They stand in a semi-circle while I explain the rules.

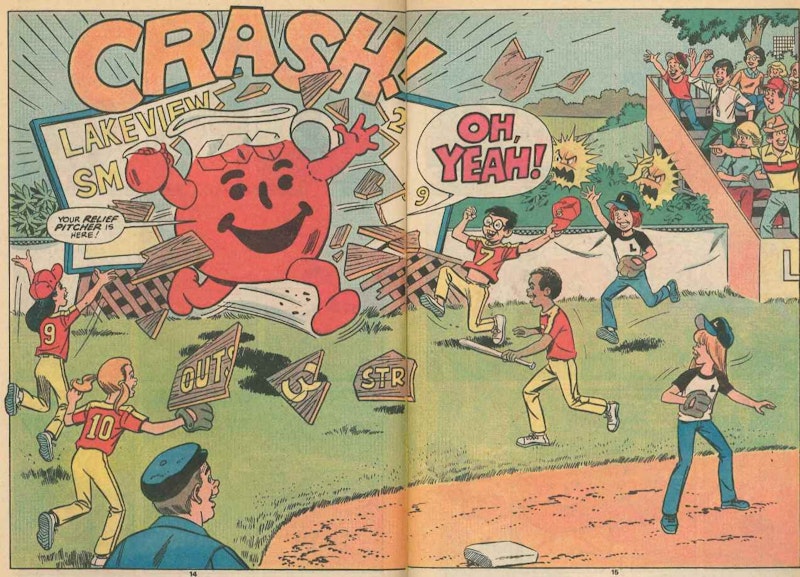

“I’ve hidden a bottle of red Kool-Aid somewhere in this school. Whoever finds it gets to drink it.” They look at me, eyes wide. Bert drools a little. Kool-Aid is crack. “You each get one clue. Three of the clues are helpful, two are absolutely useless. You can collaborate if you want to, share your clues and whatnot. Look for the Kool-Aid together. It’d definitely be easier as a team.”

“So let’s do that.” Bert gestures to the rest of the group.

“But then,” I say. “You’ll have to split the Kool-Aid evenly. You only get one-fifth each, if all of you work together. That’s, like, not even a full sip.” Jacob frowns. He’s not a big sharer. “You have to decide on teams before I hand out the clues. You can only share your clues with your teammates. If you tell anyone else your clue, anyone, you’ll be disqualified.”

“But what if we get a bad clue?” Zach asks.

“Then you’re screwed,” I say.

Bug raises his hand, presumably out of respect for the Game Master. I nod.

“What if we team up with someone who gets a bad clue?” he asks.

“Then you’re screwed.”

Everyone looks around, uneasy. Bert whispers to Peter. They both nod. “We’ll work together,” they say.

“Anyone else?” I ask.

The other three are quiet. I hold up five folded index cards. “Before I hand these out, we have to go over another aspect of the game: the green Kool-Aid.” Bert steps back. Zach says, “There’s a green one, too?”

“Yes,” I say. “And one of you already has it.”

They eye each other with paranoid half glances. “I put it in one of your backpacks like 10 minutes ago. Here’s the deal: whoever has it at the end of the day gets to drink it. But you can’t, I repeat, can’t, drink it before three p.m. Understood?”

“How do we get it if we’re not the one who already has it?” Jacob asks.

“You steal it. Duh.” I check my watch. “Okay, first period starts soon. Here, take your clues. Peter and Bert, you’re a team, you can share.”

They take their clues and run to opposite corners of the lounge. Jacob scratches his chin. His clue says: TEDDY. Bug holds his clue in the air. “It’s a piece of poop!” he yells. “It’s just a turd! You drew a picture of a turd! That’s not a clue!”

“Disqualified!” I say.

Zach is visibly confused. His clue says: WATCH OUT. Bert charges Zach, a bull trying to impale the matador. He knocks Zach down, steals his backpack, and runs down the hallway. Bert’s clue: ZACH HAS THE GREEN KOOL-AID. I smile.

The green Kool-Aid changes hands five times before third period. Every eighth grade boy—all 22 of them—is involved now. Everyone’s drinking my Kool-Aid.

I start a rumor that Josh—a quiet kid who takes advanced math classes at UMBC—is hiding the green Kool-Aid in his locker. Garret then takes a crowbar from the third floor utility closet and busts the locker open. The contents: notebooks, pencils, binders. No Kool-Aid. Jacob, Zach, Bert, and Peter run across campus, turning over every book, looking behind every shelf. They don’t know that the red Kool-Aid isn’t so much hidden as guarded. I’d handed it to coach Mac, our history teacher, with orders to give it to the first person who asks.

At lunch, I sneak an empty bottle of green Kool-Aid—one that I had discreetly drank in the bathroom, so that fresh beads of green liquid would cling to the bottle’s plastic, translucent walls—into Zach’s locker. I then tell Bug that I thought I smelled Kool-Aid on Zach’s breath, that his tongue looked a little green. Bug tells everyone. A mob forms in front of Zach locker. Zach emerges from the irate mass, scared and confused. He repeats, “I didn’t do anything” until the words lose meaning.

“Then open your locker!” Robby says. He’s the biggest kid at Calvert.

Zach does as he’s told. He turns the combination knob three times, and when it clicks, four kids reach to swing the door open. An empty bottle of green Kool-Aid falls to the ground. And then they were upon him.

The mob disbands when Paul, the kid holding down Zach’s arms so Bert could execute an uninterrupted fart-in-the-face, realizes that he, in fact, is in possession of the green Kool-Aid. It sits comfortably in his pocket. Zach goes to the nurse without any apparent external wounds. Bruises take time to develop.

It’s not until Bert tears apart Mr. Shawn’s classroom that teachers take notice of the anarchy surrounding them. Bert gets sent to the dean’s office. Peter does too. When Mrs. Lawrence asked him why he appeared so jittery and unfocused, he yelled: “Because I need to find the Kool-Aid!”

Mr. Shawn pulls me into his office before fifth period. He strokes his beard. Tugs at it, really. “What have you done?” he says.

I give him a summary of the game. I’m rather pleased with myself.

“You know what you are?” he says.

A notice appears on the bulletin board the next day. It reads, NO OUTSIDE FOOD OR BEVERAGE ALLOWED. I sigh. Everyone’s always killing my fun.