I’ve always found it bizarre how much humans love to be scared. I’m not the biggest horror buff, but will happily spend hours in the company of movies like The Thing and the more frightening episodes of Doctor Who in search of the controlled adrenaline rush that comes when my pants have thoroughly been scared off my body. (Some people, my mother included, will have nothing to do with monster movies—but as long as flicks like Pacific Rim remain profitable, those folks will be pushed to the margins by the horrified majority.)

In Top Shelf’s new children’s comic Monster on the Hill, cartoonist Rob Harrell draws a different picture of monster fans, populating the sleepy English countryside of 1867 with gruesome creatures that regularly rampage through their respective towns. But there’s a major shift in disposition between these communities and, say, Godzilla’s various victims: sure, there’s the usual panic in the streets and property damage, but everyone seems to love the attacks. In fact, the beasts are incredible for bringing in tourism, especially since nobody really gets hurt. (I can only assume most of each town’s tax revenue goes to assorted reconstruction projects, since nobody bemoans their shattered shops or carriages.)

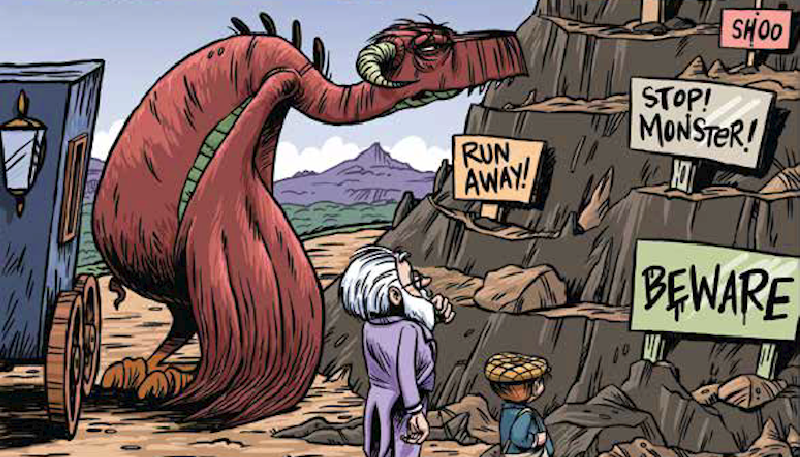

This works out great for everyone except the citizens of Stoker-on-Avon, whose rotund, horned lizard Rayburn is utterly crap at monstering. It’s mostly a self-esteem problem (though Rayburn admits he fell asleep during certain core classes at university), so disgraced Professor Wilkie and bored street urchin Tim go off to help Ray get his groove back. The rest of the plot is a pretty standard “you can do it” kids’ story, with a couple of low-stakes adventures and a villain who is defeated by water balloons and gum.

I can’t say much for the book’s plotting and dialogue, both of which are pretty flat with moments of hilarity to keep things moving. This isn’t because I dislike children’s humor—I was reading books for fifth graders all the way through college—but because there’s rarely any sense of danger or meaningful struggle. Rayburn coasts along, gets a few pep talks, and then is motivated by the “death” of a friend (who, despite being defeated by a legendary nightmare-beast who feeds on fear, turns out to be fine for some reason) to go kick some ass in a climactic battle that is won with very little apparent effort—especially on Rayburn’s part.

That last bit tastes especially sour in hindsight, since the nightmare-beast (who is known as “the Murk” and seems to represent Rayburn’s self-esteem issues in a vague sort of way) only ventures out of his lair because Rayburn left his Stoker-on-Avon unguarded. The monsters’ entire purpose is to prevent the Murk from awakening, but Rayburn’s carelessness gets his town crushed to rubble, and it’s strongly implied that not everyone made it out alive. But after destroying the Murk, everyone adores Rayburn & Co. instantly, and Our Hero gets a trading card with his face on it. It’s the same cloyingly happy ending that’s already way too common in children’s literature. (To be fair, the dialogue has some hints of brilliance—Tim’s youthful glee at discovering a box of dead rats is marvelous—but these moments of brightness come too infrequently amidst the anachronistic references to Hot Pockets and deep tissue massages.

But there is still something great about Monster on the Hill: Harrell’s impressive cartooning chops. The creator of the comic strips Adam@Home and Big Top, Harrell has over a decade of experience doing daily comic strips, and it shows in the workmanship of this book. Berke Breathed’s Bloom County (and to some extent his underrated sequel Outland) is an obvious influence, and not just because Raymond’s wings are as useless as those of Opus the penguin: Harrell’s art is detailed, his scenery lush, his colors more vivid and absurd than most Dr. Seuss books. Although we only meet three monsters, their designs look fun and creative, and the thought of a tentacle monster nicknamed “Noodles” still makes me chuckle. Some panel compositions seem a bit out of place, but with this level of craftsmanship, it’s highly unlikely that anyone—let alone a 10-year-old—will give it much notice.

When you put it all together, the cartoony joy apparent in Monster on the Hill’s execution makes its flaws far less noticeable. This is a graphic novel that’s a surefire kid-pleaser, and while it’s not entirely original in its narrative arc, there’s still a spark of innovation at its core that makes the story much more palatable. This is Harrell’s first graphic novel, so it’s understandable on a certain level that his first foray outside the realm of four-panel gag strips would be rocky. Luckily, Top Shelf plans to continue the story as an ongoing series, so readers can look forward to more creature features—and now that he’s got his feet under him, Harrell’s vision of a happily terrified England will no doubt yield some more interesting stories in the future.