What's a tree? How do you see it? Is it the same tree when it’s in bloom on a sunny spring morning as when it appears in silhouette against a stormy sky in the depths of winter? A tree consists of leaves, shoots, twigs, bark, buds, blossoms and branches. There are unseen parts too, a network of roots reaching deep into the earth and whole worlds of fungal growth which nuzzle through its fibers.

There's not one tree, but many. Each tree is different depending on your mood, on the day, on which part you focus, on how you view it and from what angle; even which species you are. The tree the insect inhabits is different from the tree the mammal exploits. The tree the bird builds its nest in is different from tree the human uses to shelter from the rain. Which tree is the "real" tree? Is the tree you can't see any less real than the tree you can?

If our perception of such a simple thing as a tree can change so dramatically, then our view of reality itself may also not be a fixed thing. There's the famous parable about the blind men and the elephant, as told in a number of different cultures.

It goes something like this. Several blind men are led into a room and asked to touch an elephant and then describe it. One man touches the leg and says it’s like a pillar. Another man touches the tail and says it’s like a rope. The next man touches the ear and says it’s like a fan. The fifth man touches the shoulder and says it’s like a wall, while the last man touches the tusk and says it’s like a pipe.

You could tell a similar story about a tree. It's a parable about the way we understand the world. We’re all constrained by our individual perceptions. You might say that these men were limited by their disability, and that’s why they couldn't take in the whole elephant, but there's a famous experiment by Dan Simons and Christopher Chabris, first carried out in 1999, which demonstrates that we’re all capable of not seeing.

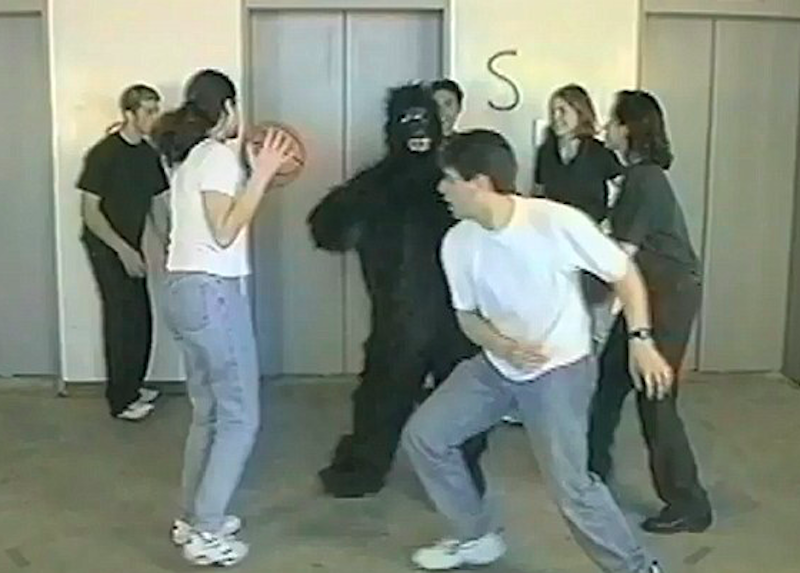

The experiment involves a video of two teams passing basketballs back and forth. One team is dressed in black; the other is dressed in white. The video lasts about a minute, and the viewer is asked to count how many times the white team passes the ball. It’s worth watching the video before you read on in order to get its effect.

The teams are darting about, dodging in and out, circling and weaving, passing the balls between themselves. It's hard to keep a track on the action, but you count the passes and confirm the result, which is then displayed on the screen at the end.

After this you’re asked to watch the film again, only this time you’re told not to count the passes. It’s only on the second viewing that you realize that in the midst of the action a man in a gorilla suit had walked determinedly across the basketball court, stood still for a few seconds, beat his chest vigorously, and then walked off again. You were too busy counting the passes to notice the gorilla in the room. It’s startling. The first time you watch there's no one there. The next time you watch, there he is, a man dressed up like a gorilla, too obvious to miss. The process is called "inattentional blindness."

What this shows is that sometimes we see only what we’re told to see. It’s this mechanism that magicians use for their sleight of hand tricks. They divert our attention from the important action by focusing our brains on irrelevant details. One hand is busy making large, showy gestures which the eye can’t help but follow, while the real action is taking place below the threshold of perception, using subtle movements that the eye can easily overlook.

So it is with the news today. Take the war on terror. It was never a real war since there was no discernible enemy as such. There was never an army. No generals. No troops. No chain of command. No political leadership. No spokesmen. No one to negotiate terms with.

It was catch-all phrase by which a diverse set of people with varying outlooks from different parts of the world could be lumped together to give the impression they were all part of the same conspiracy, united in their common hatred of the West. It was by this process that Afghan tribesmen, Iraqi insurgents, Pakistani militants, Lebanese patriots, and a dentist from Forest Gate were made to appear as all part of the same movement. The only thing they had in common was that they were Muslims.

The irony is that by declaring a war, and by acting upon it in ways that ripped real people's lives apart—by torture, imprisonment and the indiscriminate use of force—the West made it come true. We created the conditions in which terrorism would thrive.

Take that British dentist as an example. His name was Sohail Qureshi and he was jailed for four-and-a-half years in 2008. Most of the newspapers at the time suggested his sentence was too lenient, adding that he was likely to be free in a year. He was caught boarding a flight with several thousand pounds in cash strapped about his body, with optical night-vision lenses and police batons in his bag, along with two sleeping bags, two rucksacks, medical supplies and a removable hard drive containing US army combat manuals. He pleaded guilty to possessing articles for terrorist purposes and to possessing a record of information likely to be useful to terrorists.

Several of the news programs referred to him as “an al-Qa'ida operative.” He’d been on a training camp once, they said. One newspaper described him as “a hate-filled fanatic,” while another said that he planned “to fight against British and American troops in Afghanistan.”

I laughed when I heard that. He’s a dentist. What was he going to do, pull their teeth out? Even assuming he was trained, how, exactly, was he going to fight British and American troops using police batons, sleeping bags and rucksacks? Okay. He had money. Maybe he was going to buy weapons. He could probably get one or two Kalashnikovs for that money, plus maybe some grenades and a pistol. Perhaps there was even a brigade of Taliban troops waiting to meet him somewhere on the Afghan border. You have to ask, however, what use would a dentist from Forest Gate be to the Taliban, those battle-hardened mountain-men, many of whom had known nothing but war all their lives? He wouldn’t have lasted five minutes.

But it’s the comparison of resources that clarifies the real truth behind this story. The day after Sohail Qureshi was sentenced the US Air Force was in action on the outskirts of Baghdad, attacking so-called al-Qa'ida targets. They dropped 40,000 lbs of explosives in a 40-minute blitz using F16 fighters and B1 bombers.

A B1 bomber at the time cost $283.1 million. The US Air Force had 100 of them. Each 500 lb. bomb cost $283.50, making the cost of one 40-minute operation, in ordinance alone, nearly $23,000. All of that money was charged to the American taxpayer and went straight into the pockets of the American arms manufacturers. The news of a crazed dentist off to fight a fantasy war, that would have killed him before he had even fired a shot, was considered more significant than the details of an actual war, in which hundreds of people died.

The war on terror was preceded by the war on communism and succeeded by the war in Ukraine. Each of these wars segued easily into the next. Almost as soon as the Berlin Wall fell we found ourselves at war with Iraq. The war in Iraq became the war on terror, which led to the war in Afghanistan and the second Gulf War. The war in Afghanistan was hardly over before there was a war in Ukraine. And on and on and on.

Other wars were taking place at the same time: the war on drugs, the war on crime, and large and small wars around the world. The war on drugs led to more drugs while the war on crime led to more crime. The war on terror—terrorizing populations to fight terror—led to more terror. The idea of fighting a war to bring peace is an oxymoron, like fucking for virginity, or stealing for honesty. And meanwhile, behind this smoke-and-mirrors facade, this noisy game of death and distraction, some people are doing very nicely.

One man's loss is another man's gain. One man's crisis is another man's business-opportunity. The gorilla in the room is checking his share options. He made a million dollars while you were reading this.