The loneliest season a Midwesterner ever spent was a semester in the East, inside the biggest Little Hall in Princeton, closer to the Firestone One plant than Firestone Memorial Library. But for the sound of one man yelling Excelsior, but for the sound of Jean Shepherd’s voice, Walt Kirn would have gone home to Akron, Ohio. But for the greatness of Shepherd’s guidance, none of the Kirns—neither Walt nor his son Walter—would've graduated from Princeton. An exaggeration perhaps, but a probability just the same, because Princeton was cold to students from the Midwest; as foreign to F. Scott Fitzgerald as it was formidable to George F. Kennan. And yet Walt survived the fall.

Walt left Ohio during the last summer of Eisenhower’s first term as president, and left Princeton five days before the start of Eisenhower’s last summer in office. He left Akron, the air acrid and aromatic with the smell of rubber and gasoline, as factories manufactured tires and the Quaker Oats factory baked bread, driving through the Steel Belt and crossing the Delaware by taking the Walt Whitman Bridge.

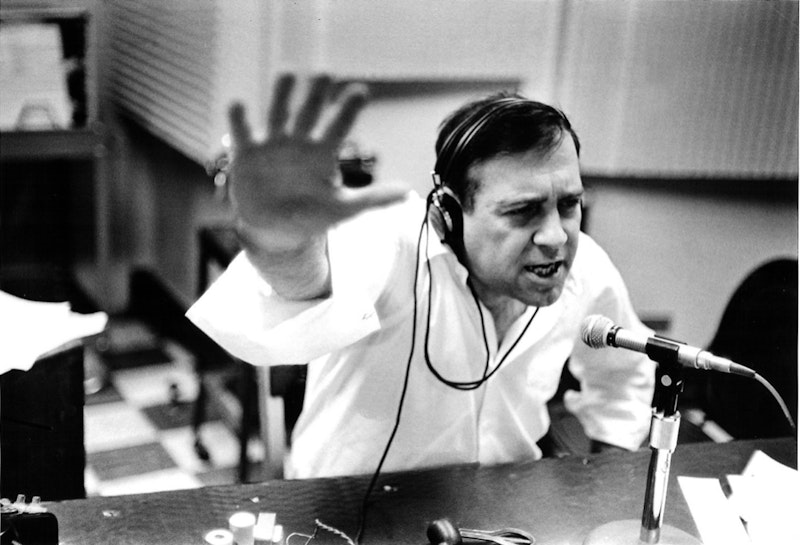

He never left home, thanks to his prairie home companion, whose voice—the voice of A Christmas Story—could be heard the year Walt arrived at Princeton. The voice filled McCosh Hall the week before Christmas Eve, the first of 40 annual performances by Shepherd.

The voice spoke to Walt, behind a curtain—beneath a speaker grille of perforated metal—from which Walt had unlocked the sound. The voice spoke to Walt while the needle shined red and the scale glowed yellow, inside of which a nightfly buzzed about a starless sky. The voice spoke of the road to Jerusalem, Indiana, and the darkest country this side of the Mojave Desert.

The voice had its own darkness too, for Shepherd was an enormous radio of tales sardonic and sad, taking listeners through the flatlands of Ohio and Illinois to the glitter of the Second City; taking America to—talking Americans through—his Emerald City of lights and vacuum tubes.

He was Sisyphus with a baseball in summer. He was plain Shep with a snowball in winter. He was a White Sox fan in Indiana, and a survivor of the whiteout that was the Great Indiana Blizzard.

He was the voice of Walt Kirn’s time at Princeton, shouting across the lawn of Alexander Beach and resonating against the vaulted passages of Holder Hall.

He was the voice of hope, speaking to Kirn without the rottenness of affectation or the affliction of carelessness.

He was the voice of adventure, roaring through dark and mysterious Ohio and the long, long skies over New Jersey, in appreciation of Twain and Kerouac.

He gave Walt Kirn the confidence to continue.

The two continue to speak for us, requiring no air to sustain them or power to propel them, traveling through the vacuum of space at the speed of light.

In their sleep, radio waves carry their voices across a sea of stars.

The two have more to say.