October 1968: Nobody said it to him, but he overheard them: the network didn’t want more episodes. Washington had no idea if this was his fault or not. The possibility couldn’t be dismissed, of course.

His heart was heavy when he stopped in the drugstore that night for chewing gum and peanuts (a favorite combination). “Mr. Show Biz!” said the owner, a fat white man with a brown mustache. Sometimes the man said this, sometimes he didn’t, and this time he caught Washington off guard. “You know it!” Washington called back, big smile, but the surprise and today’s bad news made him jumpy. To cover himself, he flung a hand over at the store’s spin rack of books, an old friend during moments of social confusion. The rack spun and he saw the black, white and yellow cover of Life and Thought: Principles of Positive Dynamism by Dr. G. Warren Heinz. Washington made a show of examining the book, and there on the back cover he saw the promise that it would set up a “thoroughgoing system of thought discipline.” All of a sudden he felt hope. Washington generally suspected he was doing the wrong thing with his mind.

His first evening with Life and Thought was briefly traumatic, but then he rallied. The introduction talked about “pickpockets.” These were thoughts that walked up to you, mentally, and tried to dip their hands into your goods. The goods included pride, zest, cheerfulness, a bright outlook. A thought could try to take a nugget from any of these and others.

Real pickpockets might happen to you in the street, of course: people walking past you might try to take your money. Washington knew that fact and feared it. But Dr. Heinz’s book taught him that the same thing, in effect, could happen anyplace else. The people followed you home. Sitting in his easy chair, the book open on his lap, Washington felt his stomach sink away from him. His lifetime ahead shrank to a narrow corridor, blank; this was now his only zone of safety and he had to walk down it until he died. Somehow he had known life would come to this.

Then Washington became angry. Because, wait a minute—pickpockets inside his head, he could tell that wasn’t fair. He knew it was too much. The rules had been set up wrong: everybody had just, well, screwed up. That’s all. Everybody, in making the rules he had to live under, had just, they had just screwed it up. Screwed it. “Hah!” Washington said to the book. “Oh my!” he added. Because, along with seeing his dismal situation, he also realized he had caught out the people in charge. It was the first time he had ever had such a thought.

He glared down at the page and found the next sentence: “As a homeowner defends his home, you too must actively safeguard your inner security.” He would never have guessed how much he wanted to see those words. But, on seeing them, Washington drew in a surprised, happy breath. His spine extended like a rod; his breath stopped racing and grew deep and even. As he read on, he found himself nodding, and at one point he snorted aloud; that was high spirits.

Washington took pride in never fooling himself: he realized that the book’s introduction and the news there had turned his life upside down. But he felt armed to fight. “Collar the culprit!” the book said. “No need for fear: the confrontation takes place in your own inner fastness. You are master and law here, and thoughts must cede to your authority. And so they shall, when you impose your conscious will. Look that thought in the eye!”

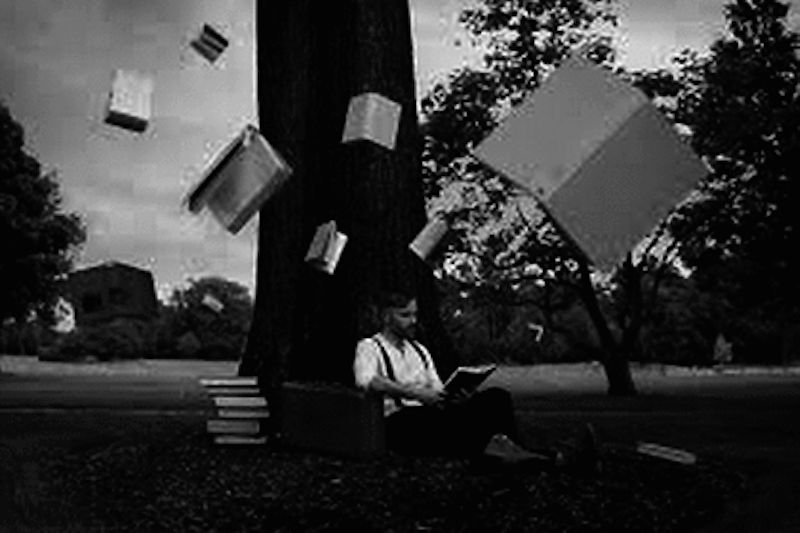

That night and the next, he spent his free time on the book. He had to get to bed early, and reading the book at the set was out, what with everyone being there to see. But he made it through and he did it fast, thumbing the pages, holding the book folded back in one hand. Everything in it excited him.

“I see you!” Washington declared on the second night. “You want my fortitude.” The thought had tried to tell him that Len Bacall considered him weak because Washington had looked down instead of up when Len had been talking to him.

He was speaking toward the shadowy bookcase next to his bedroom. The voice was his own; he didn’t imitate anybody. The dark looked back at him, but Washington stared it down. Two years back, when he decided that he would learn how to drive, Washington had set foot on his path to change; he had made the resolution to fix his life. But, day to day, you couldn’t always tell where the path was. Life and Thought reassured him. When he acted on its lessons, he felt free. The day when he could stand among others, look them in the eye, came a little closer because he was doing as much right now, inside himself.

He could do a little of this at the set. “You shall not have my time!” he thundered, silently, when he caught a barefaced thought sneaking into his head, insinuating to him he might drag his heels on the walk back from the toilet. (A short-tempered, bristly director awaited him there, the one with the beard. The director never showed any temper toward Washington, who delivered exactly the desired goods on take after take. But Washington felt churned up just because an outburst might be possible.) At home he could give full leeway to his regimen. He spoke aloud. He wheeled and barked. He did it without doing characters; as far as he was concerned, each time he was being himself.

The practice reached a climax of sorts about three weeks in. “No, sir!” he said, finger directed at the set of golf clubs with which he liked to take practice swings in his living room. He didn’t mean the golf clubs, though; he was just pointing so his finger could impale a patch of the dark. Because, on coming home, he had been struck by the suspicion that his Thunderbird might have been scratched, even though he knew he had looked the car over carefully the last time he had visited the building’s garage. He confronted the thought, his anger building as he spoke. “Don’t look there,” Washington told the patch. “Not there, neither. You gonna look at me.” He was peremptory. “I got the eyes. You don’t want these eyes, this not the apartment.” His grammar had gone to hell, it had become hoodlum-style, as his mother would have put it, and yet he recognized the voice as his own, not a put-on. The fact should have scared him a little. Instead it gave him a lift, like oxygen flooding the brain. His words scudded out. “You tried what you tried, now you face up to it,” he said. “That being a man. All right? That a man.” It felt like talking with your fly open and still being right and knowing it, and nobody was able to say you were wrong because they knew you were right. “You want to take my ease of consciousness?” Washington said. “Then you putting your hand where it don’t go. That ain’t yours. That mine.”

Washington talked for a good part of the evening. He dwelled on the nature of the thought’s offense, on the why of its guilt, because Dr. Heinz’s book had contained useful asides on the harm such thoughts inevitably did. “That’s my productive energy and good cheer,” Washington said. “That’s the internal harvest I use to sustain my efforts during the day.” Life and Thought had two pages where a chart showed a pair of boys side by side, and they grew up and the boy on the right became a man in a suit and tie, with an auto and a house standing behind him, and the boy on the left grew up to wear overalls and to carry a lunch bucket, and behind him was a sign that said BUS STOP. One leg of his overalls had a rectangle above the knee, representing a patch. In between the first and last stages came some drawings of the boys growing up, and what you saw there was all their thoughts at work. In the case of the boy on the left, the thoughts showed up as hands. They crowded about him, and as he aged from teenager to young man to full-grown man, the last stage, they plucked little glowing packets from him. Some of the packets had notations in parentheses: “(Normal optimism)” or “(Honest pride).” Meanwhile, the right-hand figure’s glowing packets kept accumulating. In the last drawing, the one with the car and the bus stop, you saw the right-hand man surrounded by a deluxe version of the glow, straight long lines that radiated from him, and along their perimeter read the words “A lifetime’s bounty.” The left-hand man had a perimeter of wilted, sparse lines. Along them read “Cheated and deprived.” Two more of the hands floated to either side of him in a proprietary way.

In haranguing his captured thought, Washington did not refer specifically to the diagram series. But he knew that the diagrams had made him especially angry. A man’s life could be taken away: it came down to that. Toward the end of the evening he saw a diagram in his mind’s eye. It wasn’t from the book; he imagined it all himself. “Everything I build up is vulnerable to you,” he was saying, because this late his grammar had wandered back to normal. “What I make for myself, you treat as your own.” And here he stopped because he saw a cutaway of himself, he saw his heart hanging like a rich man’s wallet but sheltered in its nest of ribs, protected. When the pickpocket reached its hand into him, it reached for that. His heart was inside, and everything else was outside, and the world did not have the right to interfere there.

Washington’s mouth shut. For a moment he felt no need to make the arguments he had been making for hours that day and for weeks beforehand. He realized he had a self.