Every so often I’ll get to the end of a book and be so impressed that I’ll start reading it again. There must be something in the book to which I can relate on a personal as well as intellectual level. One of these books was Witness Against the Beast: William Blake and the Moral Law by E.P. Thompson.

Thompson, you might know, was the avowedly Marxist historian most famous for The Making of the English Working Class, a study in the shift in social relations that took place during the Industrial Revolution. It’s probably the most influential work of academic history to come out of the United Kingdom, and Thompson is one of our most well-known historians. Witness Against the Beast is Thompson’s final work, an altogether smaller book, focusing on the poet and engraver, William Blake, who was alive during this period. It’s an attempt to discover the specific tradition out of which Blake’s ideas arose.

I first heard about it in the early-2000s. A friend told me he’d seen it on the shelves of another friend’s bookcase. I was engaged in writing my co-authored book, The Trials of Arthur, at the time. This is about an ex-biker turned Druid who identifies with the historical-mythical figure of King Arthur. The co-author was Arthur Pendragon, the subject of the book. It involved a lot of journeying to Glastonbury and the West Country to meet Druids and other such magical folk, while consuming hard cider, and discussing Celtic history and mythical kings in an atmosphere of weird mystical speculation.

Meanwhile I lived in Kent, in the South East, an Anglo-Saxon stronghold. I felt very split. On the one hand I had what I called my Western Mind, which was the one supposedly writing the book. This was mystical, speculative, poetic in nature, engaged in such ideas as reincarnation and Celtic legend. It was most engaged in Glastonbury. On the other I had my Eastern Mind, where I lived, which was pragmatic, political, down to earth, caught up in protesting against the War on Terror, which was the current issue at the time. My Eastern Mind was in the ascendant and not much writing was taking place. I preferred standing on the High Street handing out leaflets and organizing against the war.

I went to my friend’s house and said I’d heard they had a copy of Witness Against the Beast and asked if I could borrow it. They graciously allowed me to take it home with me. I immersed myself in it. As I say, it’s an attempt to discover the intellectual tradition out of which Blake was operating. He was no academic. He was a working engraver, skilled but eccentric. You can see him as an artisan rather than as an artist, self-educated: more like a cabinet maker or a tailor than an oil painter exhibiting portraits in the Royal Academy or a scholar involved in polite academic debate.

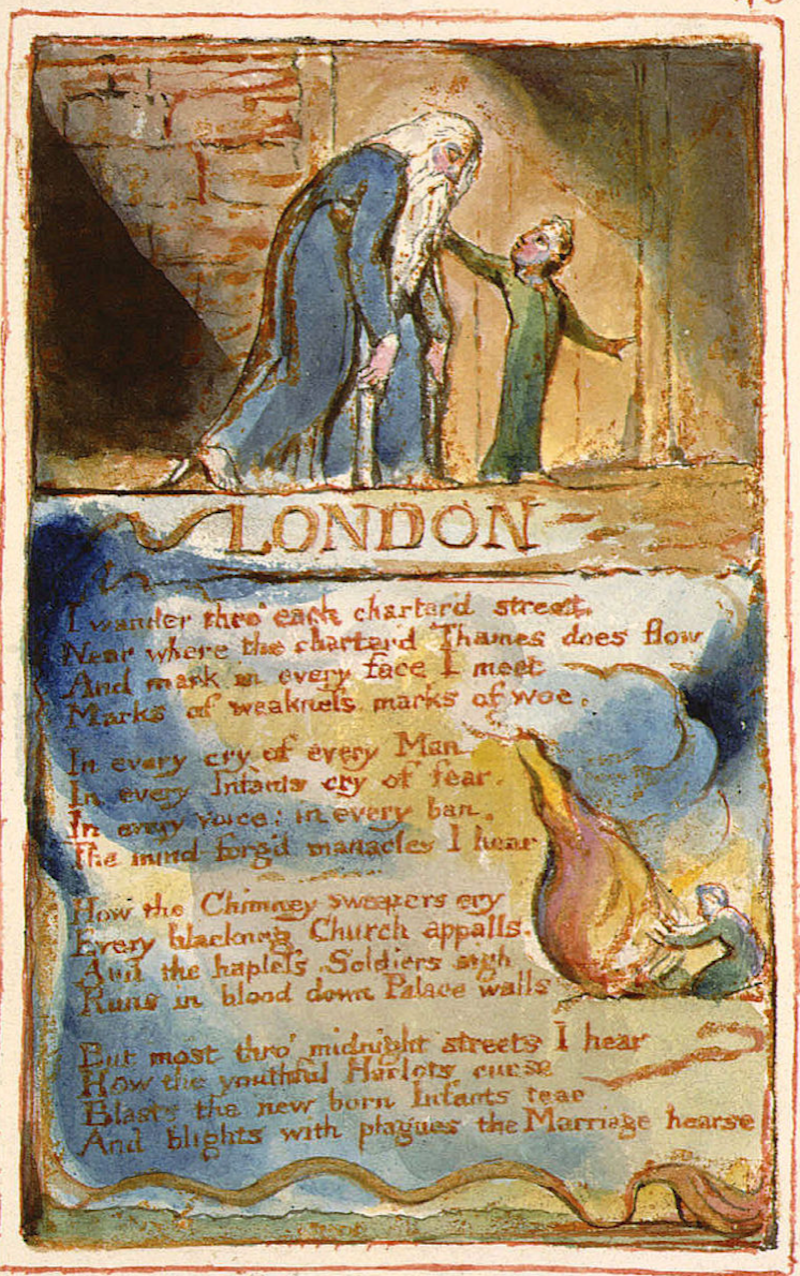

What Thompson does is to locate a particular strand of English intellectual history that he calls Antinomianism, or the English Dissenting Tradition. “Antinomian” means “against the law.” It’s a form of Christian thinking that eschews the Jewish law of the Old Testament, and focuses instead upon the idea of free grace in the New. Grace is given by the love of God, and no amount of adhesion to strict laws can determine whether you’ll receive it or not. It’s a form of millenarian enthusiasm that has its roots in the Christian faith. In Britain it was at its most overt during the English Civil War when the censorship laws had broken down and there was a rash of mystical, political and revolutionary tracts available, attached to various dissenting groups, including the Baptists, Quakers, the Fifth Monarchists, Levellers and the Diggers, amongst others. He traces Blake’s milieu back to that time and to that tradition.

Thompson opens the book with a discussion of The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan, which was written in the period of repression following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Bunyan began his work while in prison. He’d been holding religious services outside the auspices of the established church. The Pilgrim’s Progress is a work of dissent. It was at this point that my sense of personal engagement kicked in. Bunyan was the composer of the hymn To Be A Pilgrim, which always stirred my heart when we’d sung it during assembly in my school years. Along with Jerusalem, it was one of my favorite hymns; and now here was Thompson, another hero, laying out a direct connection between the two. I began to imagine a strand of history of which I was a part, a secret lineage that led directly from Bunyan in the 17th century, to Blake at the turn of the 18th and 19th, to Thompson in the 20th, to me now, at the beginning of the 21st, protesting against a war.

Later things got muddled up in my head. Arthur had grown tired of the delays and had arranged for me to stay in Glastonbury, the famous Isle of Avalon, at a friend’s house. There are well-known mythical and historical links here to the legend of Arthur. Camelot was supposed to have been located at nearby Cadbury Castle, while Arthur is said to have been transported to Avalon to recover after his wounding at the Battle of Camlann. It’s from here, so the legend goes, that he’ll return when the Isles of Britain are in mortal danger.

I was working on the book by day and then reading it out to my friends in the evening. It was a creative time. One day Arthur turned up and we threw a party. Eventually, exhausted by it all, I went to bed, but, overstimulated, couldn’t sleep. I found myself caught up in a vivid fantasy. I decided that I’d been Chretien de Troyes in a previous life. Chretien was the 12th-century author of a series of book-length poems about the court of King Arthur which kick-started the enthusiasm for what was known as The Matter of Britain. It was an enthusiasm that swept the Continent, leading to many books on the subject in a variety of languages written over a period of centuries. Chretien was at the root of this. Specifically he’d come up with (or read about) the notion of the Holy Grail, the symbolic object that lay at the heart of the story.

Chretien never met Arthur, who (if he ever existed) would’ve been a Dark Ages battle chieftain rather than a medieval knight. That’s what our modern Arthur was like: a biker chief on his iron steed, more rough and ready than the romantic depiction. I decided I was Chretien, the inventor of the literary Arthur, meeting the historical Arthur for the first time. The Grail story involves a procession. Four objects are paraded before the seeker. Jessie Laidlay Weston, in her book From Ritual to Romance, identified the four objects with the suits of the Tarot, which she referred to as the Grail Hallows, these being: swords, staves, cups and disks.

I was excited as this went through my head. I rushed upstairs, where the party was still going on, to tell everyone what was happening. As I stepped into the room my eyes fell on a number of objects. There was Arthur’s sword, leaning up against a wall, alongside his staff. There were a few other staffs in the room too. These were Druids, remember. Then I looked down and on a small table in front of me there was an elaborate, medieval-looking silver goblet with a stem, not unlike the one represented as the Ace of Cups in the Tarot. It was sitting on a circular silver tray. So there they were, the Four Hallows of the Holy Grail, right before my eyes, a sword, a stave, a cup and a disk, confirming what went through my head only moments before. All of this must have come pouring out of my mouth in a stream of excited blathering as I demanded that Arthur knight me there and then, which he duly did.

This was the third time I’d been under Arthur’s sword. The first time was when we’d met, in the 1990s, when I was writing a book about the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act and he was involved in a road protest, which is one of the things the Act was designed to stop. I was raised as a Brother Knight at Avebury stone circle: as he said, as someone whose feet were firmly planted in the 20th century, but whose values ran parallel to his own. The second time was when we’d secured the contract to write our book together. Then I was raised as a Quest Knight at Stanton Drew stone circle near Bristol. My quest was to write the book. Finally, this third time, in Glastonbury, in the shadow of the Tor, I was raised as a Shield Knight: as someone who knew what his true identity was. Too many nights spent in Avalon can do that to a man’s brain.

I’d already read Witness Against the Beast and, after going back to bed, added a couple of names to my imaginary lineage. I was also, I decided, John Bunyan and George Orwell. This was partly based upon the coincidence of names, “Chretien” another form of “Christian” which is the name of Bunyan’s famous character in his novel. It had also been my assumed name for a while: James Christian. I’m less sure now about Orwell’s role in this, except that I identified with him as a dissident socialist and an Antinomian prophet: as someone who went against mainstream opinion in left-wing circles.

Anyway, that was my fantasy, brought on by chemicals late at night in the mystical Isle of Avalon. Do I still believe it? Yes, but in a metaphorical rather than a literal sense. Between them Chretien de Troyes, John Bunyan and George Orwell represent my intellectual lineage. They are writers I’ve learned from. All of them used allegory. All of them wrote for a popular audience. All of them created a lasting legacy, something that I still hoped to achieve.

Meanwhile, I was marrying my Eastern Mind with my Western Mind, adding politics to mysticism and bringing King Arthur into the same space as E.P. Thompson. The result was the book, The Trials of Arthur, by CJ Stone and Arthur Pendragon, completed within the year. It was first published in 2003 and then revised and extended in 2012. It’s a book about protest and spirituality, about Celtic Romance and the Criminal Justice Act, about fighting for the land without going to war; a book about spiritual revelation and political rebellion, all at the same time.

—Follow Chris Stone on Twitter: @ChrisJamesStone