John Darnielle’s new novel Universal Harvester starts at the end of the 1990s, when media properties were still printing money. Magazines and newspapers were hundreds of pages and bulging with ads; new CDs and DVDs often cost 20 bucks or more; a band like Stereolab could be on a major label; and brick and mortar stores were still necessary and thriving. We meet Jeremy Heldt when he’s 22, working at Video Hut, an independent video store surrounded by chains like Hollywood Video and Blockbuster. “In the dark you could see how temporary it was.” Starting here at the turn of the millennium immediately brings the reader their own sense of loss and impermanence: we know these chains will be gone in a matter of years, too. Reflecting on customs that have come and gone: “Some stores had slots in the counter that dropped into a big bin, but Nevada was a small town. A little cleared space off to the side of the counter was good enough.”

Universal Harvester is filled with people half-dead from grief: Jeremy lives with his father Steve, six years after his mother died in a car accident. They’re both broken, in a perpetual emotional hibernation. Steve chooses stasis and stagnation over the unpredictable and uncomfortable state of mind of the ambitious. Why change the world? Why not make a nice life for yourself wherever you’ve ended up and ride it out?

“The two of them had shaped the space they lived in around his mother’s absence; they’d made it a comfortable place you didn’t have to think about too much. It was a known quantity, a knowable outcome. In local terms, that was its strength, but some nights at dinner Jeremy looked at his father and felt a sadness he couldn’t quite name.” Settled into a life that led comfortably all the way to the grave, only to have the track break and throw you deep into the woods. People spend their whole lives trying to cope and understand with their long-term expectations and understanding of the world obliterated in an evening. At 22, Jeremy has already imagined his own cocoon: “When he imagined himself all grown up, he saw himself in Nevada, maybe owning a store, or managing a business in Des Moines. If he thought of the future at all, it looked like the present.”

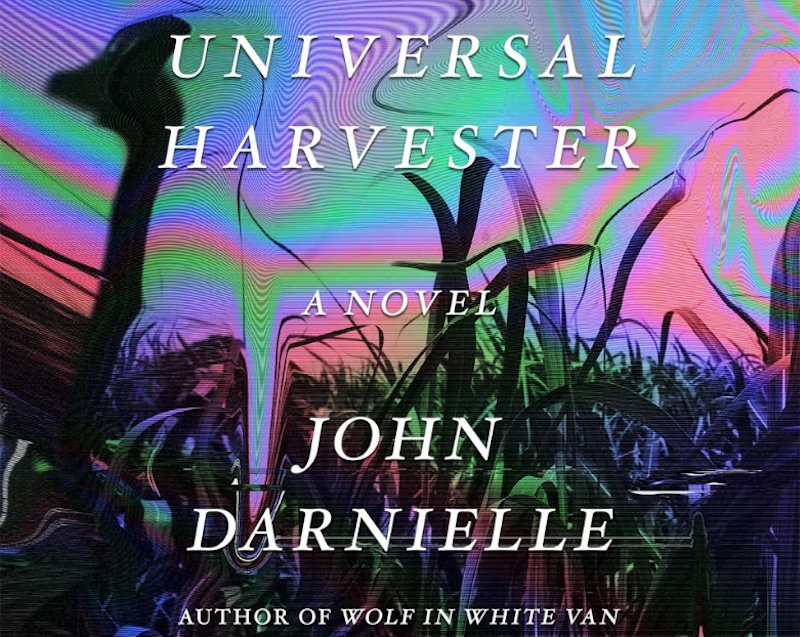

The book’s slug-line synopsis (kid works at a video store when customers start reporting unusual and disturbing scenes intercut onto the tapes) and the unnerving book trailer (!) suggest that it eventually ends up all blood and guts, but the horror of Universal Harvester is closer to the existential horror of Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York than The Ring or early John Carpenter. There are few screams, no dramatic showdowns, nothing quite supernatural. As Darnielle leaps back and forth in time—first from the 1990s to the early-'60s and -'70s, then finally to the present—we see the balance of things falling apart: bodies, relationships, small towns; and others that things remain untouched: parenthood, outbuildings, cornfields. To walk for 10 minutes into the heart of a cornfield knowing you could be killed and no one would find you until the combine harvester comes in October.

Colossal loss, especially when it’s completely unexpected, makes one feel as if they’ve been thrown into an alternate reality, non-canonical and perverse. The horror and dread of this book isn’t in the events but their echo, and how they howl within us for years. Universal Harvester conjures a real dread that we feel every day, knowing the world could throw us into a thresher at any moment for no reason at all: the silence and indifference of the universe is scarier than any image of the grim reaper or a supernatural slasher.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1992