The temperature is about 22 degrees in Antrim, New Hampshire. Snow flurries are predicted. Downstairs, my wife is playing the piano, exploring the classic songs of Hoagy Carmichael, Kurt Weill, the Gershwin brothers, and a dozen other composers. For some reason, summer times of long, long ago, come to mind.

Music was always around when I was a kid. I took it for granted, as one does the air. Yet that omnipresence is modern. The spoken word was first broadcast in 1906, a year before my maternal grandfather, Kenneth James Hart, was born. The first commercial music broadcasts were in 1923. Since then, between Muzak, the transistor radio, and the boom box, music became inescapable.

While I washed dishes six and seven nights a week to pay for college, summer nights became pervasively, intolerably hot. Perhaps Merle Travis wrote the song better associated with summer as it was for me then:

You load sixteen tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt.

Yet recalling that discomfort takes effort now: my memory lets unhappy memories fade away.

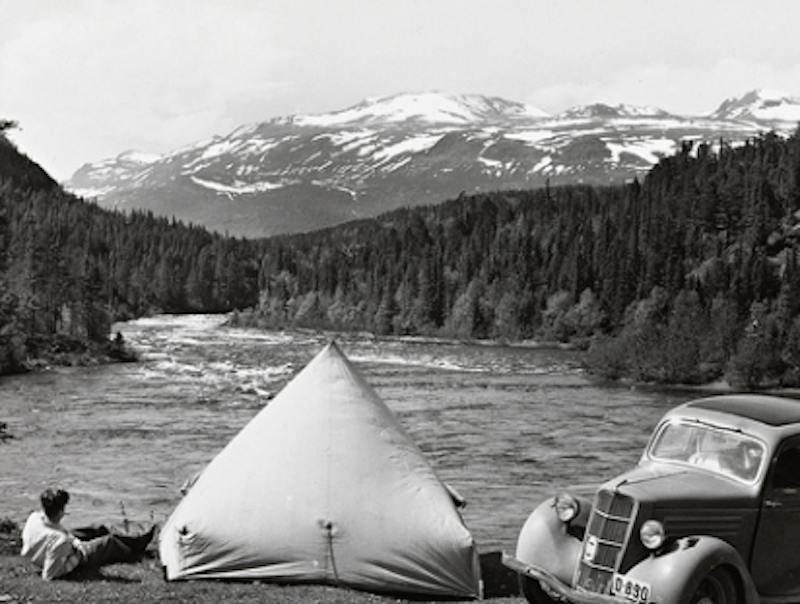

It’s easier to remember a pleasant July morning, the clear light shining green through the leaves, the heat of the day not yet arisen, when I was four years old. We then lived in Waterford, New York in 126 Saratoga Avenue, a Victorian upper-middle class house subdivided into apartments by our landlady, Ms. Bartholomew. She was a kindly, imposing dowager, reminiscent of the British actress Margaret Rutherford. Her equally imposing gray 1938 Packard limousine rested in a pale yellow wooden garage in back of the house.

My mother was cleaning. She put an album on the hi-fi. I don’t recall hearing music before then. Suddenly Frank Sinatra was singing Porter’s “Night and Day,” in a gently romantic Nelson Riddle arrangement. I remember all this because I’d studied the album liner notes with the same rapt, indiscriminate attention I gave the Albany Times-Unionor The Little Engine that Could, my parents having taught me to read well before kindergarten. Sinatra must have made the recording at the height of his gifts, singing with rich, seamless, effortless grace. It was and is so unlike the audible strain and forced emotion of his later hit, “New York, New York.” Perhaps listening to him singing those two songs helped me understand a great artist can be both poet and poseur.

I’ve never heard anything that sounded so modern, or, better yet, timeless, as that song in that arrangement. And when I hear that recording, the memory of an early summer morning’s cool, golden light returns.

Or roaring up the Northway to Saratoga in 1962 with Aunt Judy in her fire-engine red Thunderbird, sipping her homemade lemonade (alas, she was a loyal sister to my mother: there was no booze in my tumbler, which might have helped develop my character) and hearing Nat King Cole’s “Those Lazy Hazy Crazy Days of Summer” on the radio. We rushed across the then newly-opened bridge spanning the Mohawk River, heading for the racetrack to watch horseracing. Some 30 years later, while browsing in a Greenwich Village second-hand store, I saw a set of the same kind of aluminum tumblers as those from which I’d sipped in the T-Bird. Now, they were $60 for 10. I’ve outlived the Packard and the Thunderbird. Even cups from which I’ve taken drink are antiques.

Yet the tradition endured into my childhood that the only sure way for most people to enjoy music was to perform it themselves. During the mid-1960s, my mother somehow obtained an old upright piano, with huge piles of old sheet music under the hinged seat of the black-lacquered piano bench. The sheet music hadn’t been inexpensive in its day, either. The copies of “Peek-a-Boo,” “Daisy Bell” (better known as “A Bicycle Built for Two”), “And the Band Played On,” “The Bowery,” and “By the Light of the Silvery Moon” had cost 50 cents each in 1905, when the average weekly wage was $12.75.

We then lived at 157 Columbia Street, Mohawk, New York, out in the middle of the Mohawk Valley, near Utica. Within 15 minutes of leaving that house, I could walk into the fields and woods north of town, where farming had been dying since the Second World War but the suburban sprawl was still a generation away. I lay down in the grass and gazed with mindless pleasure into the rolling clouds and the endless sky. I’ve done nothing like that in over 50 years, yet I recall its utter delight, the sort of emotion that may come only when one doesn’t worry about making a living and time seems infinitely expendable.

The shadows were lengthening one July afternoon, as I plodded into the driveway from another daylong hike. I heard the piano’s notes and my mother’s soft alto:

Come away with me, Lucille,

In my merry Oldsmobile.

Down the road of life we’ll fly,

Automobubbling, you and I.

To the church we’ll quickly steal,

Then our wedding bells will peal,

You can go as far as you like with me

In my merry Oldsmobile.

Gus Edwards’ lyrics were risqué in 1905. Some of the other songs were still a trifle risqué for my mother, even in 1967. Still, they spoke to her as other songs had not, and because she played them throughout the good old summertime, I think of them.

Twenty-five years ago, I was seated on the back porch of a villa in the Algarve, in southern Portugal, with a gin and tonic (very large, very strong). The house looked south, out over the Atlantic. The sweat of the day had cooled. My skin felt taut and warm from the sun. A mild breeze arose off the sea, out of Africa beyond the far horizon, as the cloudless eastern sky deepened to indigo, and Sinatra’s “Night and Day” suddenly passed over the fence from a nearby house. All I knew was summertime.