Ed Wolf died in 1973. He taught me about skinning a catfish in the early 1960s when my dad sent my big sister and me to spend summers with the parents of our deceased mother so we could keep a connection to her instead of wallowing in the swelter of another Baltimore summer. I was skinny, with red hair, freckled, and not much taller than the rusty oil drum out back in the garden under the apricot tree that was so spindly it bore little fruit. That particular patch of soil in dusty Apache, Oklahoma was a favorite spot for the neighborhood cats. Kitchen scraps lay strewn about the weeds, becoming compost. Grandpa Ed used the 55-gallon drum to burn trash. Inside it was sooty and smelled like burnt paper. A concrete block was beside it in the dirt. A piece of plywood leaned against the drum. Grandpa Ed used it as a fish-cleaning table whenever we came back with a catch.

After one fishing trip, we tramped along the worn path to clean our catch. It was there in that mystical space of childhood awe that I got a simple lesson in fish cleaning. It’s only in adult retrospection that I grasp what I was being shown.

"Grammpa, Grammpa, I wanna do it. Lemmee clean my fish. I can do it." I bounded ahead, my arms flailing, my eyes bright with glee at having caught the biggest fish. The string of catfish, perch and crappie hung heavy as a dead weight from Grandpa Ed's outstretched arm. His arms were always weathered, browned and tough like his hands, but the rest of him was pale, except for the "V" at his neck. He wore gray khaki work clothes with the sleeves rolled up. His nose was sharp and his gray mustache was thin and neatly trimmed. He just trudged on, solemn.

"You just watch, now. Maybe I'll let you have a whack at one of them little bitty ones," Grandpa said, arriving at the drum. He thrust the chain supporting the dozen fish toward me. "Hold this now. Mind me and we'll see.”

"But I wanna clean my fish," I protested, not caring that the one I caught was nearly as long as my arm and fatter than my leg. It had fought like a shark, and I had help reeling it in. Its head was huge and leering with its dead eyes. I imagined movement in those bulges. I took hold of the small chain that held the fish spaced evenly on hooks like giant safety pins. It sagged in my frail arms. My shirttail pulled out as I strained my arms to keep the fish off the ground.

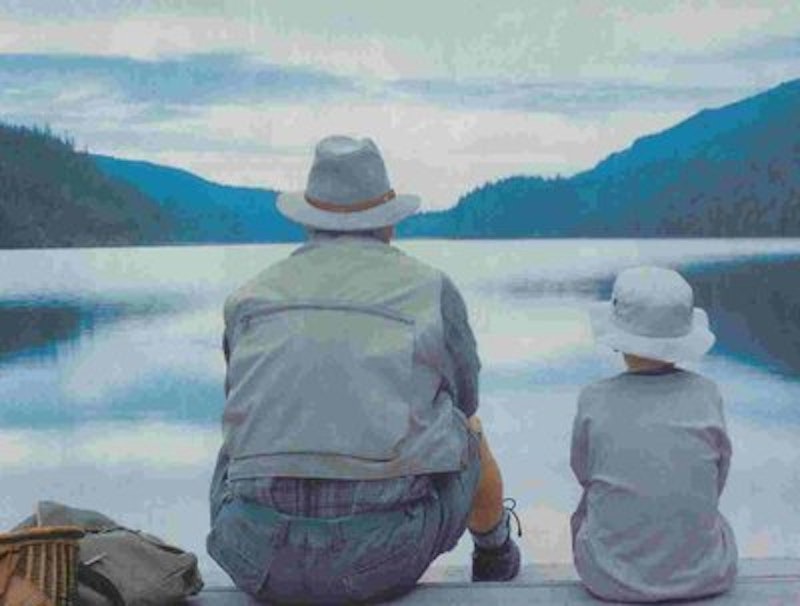

"Don't drop it, now, dadgummit!" Grandpa was not really mad as I glanced down and saw two of the fish dragging in the dirt. He used such expressions out of habit and Baptist inhibitions about swearing. I strained and the fish dangled in the soft light of the late morning. We'd gone out on the lake earlier in the skiff. Scales shimmered in the sun, catching light like mica flakes along stream banks—except for the catfish. Their skins were smooth and shiny. Some had brownish-blue splotches, but they all glistened. Perhaps the spots were catfish beauty marks or toxic deposits.

"Hand it here, now, and fetch me the hose." He took the fish and hung it from the limb of the apricot tree that was above the oil drum. The sudden lightness made my arm feel like a balloon. Grandpa then set up his cleaning table as I sprinted to the spigot, turned on the water and ran back, unwinding the hose. The fish spun as I squirted them off and the plywood.

Grandpa swept his hand across the wood and placed the big stainless steel bowls on the board. He also took the knife from its nail up high on the tree trunk and put it on the table. He had me fill the bowls with water, and then I set the hose down by the base of the tree. There the water would run into a furrow for the green beans that would grow and end up washed and snapped into bowls on the porch with Grandma. "Now get me that first one."

"This little perch?"

"That's fine. Just wrench it off and set it down." He spoke as he swiped the knife back and forth across a whetstone from his shirt pocket, honing the edge.

I took hold of the big catfish I’d caught which now hung beside the perch. Catfish have long whiskers and three barbs with sharp tips like cactus pricks just behind their heads. They'll snag you sure when the fish is flapping on the end of your line. Even dead, you have to grab them just right. I got stabbed in my little finger anyhow as I gripped the perch and twisted it off the clip.

"Ouch!" I wailed slapping the perch on to the table. I squeezed my poked finger.

"Be careful how you handle things with barbs and thorns," Grandpa said with a hint of wry affection, "or life may stick you." I merely looked on and sucked my finger. I glanced at the catfish, sure that it had stuck me for taking it from the lake.

Perch scales spun away as he scraped with the knife, glittering as they flew in all directions. I stared in awe like I always had as he skillfully and methodically slashed the perch into a fillet ready for Grandma's frying pan. Then he dunked it in the rinse bowl and set it in the second, larger bowl. That bowl steadily filled with cleaned fillets from our catch. Standing on the concrete block, I helped do a perch and a crappie. They were easy. He left the big catfish for last. It seemed to grow bigger all by itself.

Catfish weren't so easy to clean, but maybe not as messy as scales. Grandpa used needle-nosed pliers along with his curved knife with the saw edge on top and an antler handle. It was the moment of truth. He reached up, took the fish and rinsed it couple of times before laying it on the table next to the ruler he had once whittled into the surface with the knife.

"Over a foot and a half… You ready?"

I stared at his blank expression and then at the fish, whose one visible eye seemed to follow my movements. But, of course it was dead; its antenna-like whiskers were motionless.

Again, I placed my hands over the head, wary of the barbs and tried to remember what to do next. The greenish-gray head was clammy, slick and wet. I took the knife and held the head like a loaf of bread, and was ready to slice down hard behind the neck and cut off the ugly head. Grandpa's hairy, tanned arm stopped me.

"Hold it now. You'd better let me do this one. You'll never get the skin off that way."

"But don't we have to gut it, Grammpa?"

"Well now, mind me and just watch. There are certain steps you have to go through in life if you want results." Then he put his arms around me and placed his hands over mine on the fish and the knife. The warmth of his body on my back sent a ripple up my spine. "Here now—make little cuts like this."

He spread the three barbs wide—one on top, two on either side of the head—and proceeded to make my hand saw shallow cuts behind each barb. Then we set the knife down. He took the needle-nose pliers and got a grip on the cut flap of skin behind the top barb.

"What are you doing now?" I leaned forward to see better. He had begun to tear the skin back.

"I'll do this first side. You use the barbs to tug against—see?" He had the head gripped with my hand sandwiched in-between, with the barbs sticking out beside our fingers. He held the head firmly on the table as he stretched the skin up and back toward the tailfin. It made a slurring sound like yanking duct tape up off a rug. I tried the next side. It took three times before I gripped hard enough to keep the pliers from slipping off.

After it was skinned, we turned the fish on its back. Grandpa guided my hand on the knife as we slit the belly open from tail to throat. The insides pushed out, all blue and gray and red. There was also a little white balloon-thing Grandpa said was what helped the fish float.

We rolled the fish back onto its belly and then it was time to cut off the head. I needed his strength because that fish was tough like rubber. Finally the knife snapped through the bone with a soft crack. Then Grandpa put the knife down. We took the head and the fish, which were still partly together, and held the fish part down while his left hand twisted the head all the way off with a gurgling sound. The guts came along after it. The colors and textures of the stringy entrails hanging in the air that morning formed an indelible impression. My hand on the head let go as he flung the dumb head into the weeds where the cats were already greedily tearing at the other fish heads and guts.

"Now scoop out the rest," he directed, handing me the knife. I took it and lifted the slit belly. Inside was gooey and mashed. I used the curved edge to scrape and soon had it clean. I tossed the rest of the blob of insides to one little cat that seemed to be missing the main horde. It snatched up the mess and darted away. I sloshed this last fish in the rinse bowl and Grandpa dumped the water. He took the bowl of cleaned fish, held his hand across the lip, and drained it.

"That one was a little big for a little boy, but you did just fine. I'm proud of you. You're going to be a good fisherman if you're not afraid of sticking your hands into something you don't like."

"Thanks Grammpa. Thanks for letting me do it."

He smiled and nodded at me with approval and tousled my mop of red hair. "Your Grandma's going to make you get that hair cut soon. Finish up and get ready and wash up for dinner.”

The noon meal was dinner and breakfast had been at five a.m. I was hungry. Grandpa trudged off to the farmhouse and I took the hose and squirted the area down, scaring away the cats who’d return later. I placed the plywood against the oil drum and reached up and slipped the ring on the knife handle over the nail in the tree. The sooty odor in the drum was now wet.

I went to the spigot beside the storm cellar, turned off the water, and tugged the hose in, hand over hand, winding it into a circle. I vaguely grasped that I’d received some sort of lesson but I thought it was only about cleaning fish. I always enjoyed fishing with my Grandpa Ed and the rare times he shared himself. I’ve never liked gutting fish and I wonder if it has something to do with my approach to other life challenges. Perhaps simple wisdom of a grandfather who was a farmer and a righteous, plain talking man held a clue that day. Perhaps, if I’d been bigger, I might have done the whole thing myself. I wonder if my approach to life would now be any different if I’d sensed a connection at the time.