I teach art classes and often ask my students to name their favorite artist. The name that comes up more than any other is Vincent Van Gogh. I hear explanations like “he suffered for his art” or “he’d rather paint than eat.” This is true. Van Gogh gave his life for his art. In the process, he became an iconic role model. I know this because he’s always been a role model for me. But Van Gogh is a terrible role model, and I’m ready to give him up.

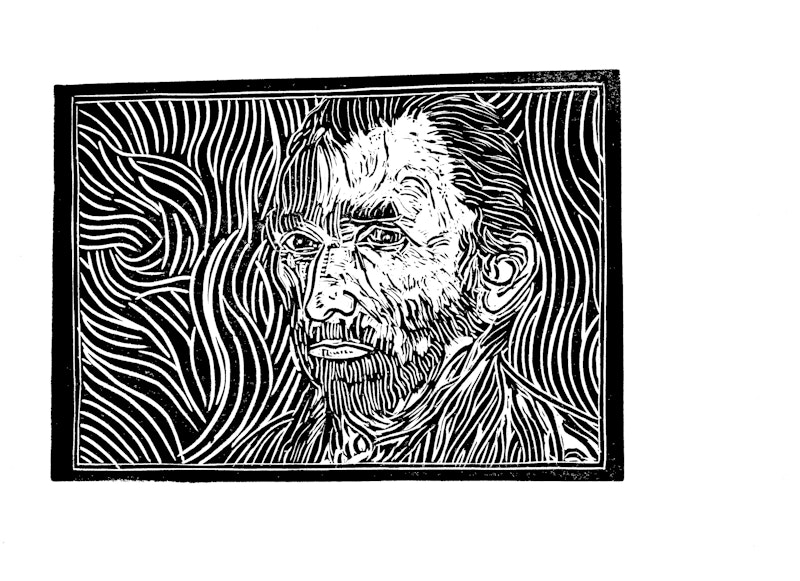

I create art both as a writer and a printmaker. The Van Gogh energy field has not served me well. Mind you, I’m not comparing myself to Van Gogh the artist. I’m referring to Van Gogh the life coach. The Van Gogh who were he alive today would likely host a podcast on living your life as an independent artist. This is the Van Gogh I’m eager to expunge. The struggling Van Gogh, the miserable Van Gogh, the Van Gogh that paints a life picture of pain, hardship and death. If a 12-Step Van Gogh Anonymous group exists I’m ready for an intervention.

First, let’s recap the Van Gogh ethos. Van Gogh was dedicated to suffering. Like Nietzsche, he believed melancholy had creative value. In one of his letters to his brother Theo he wrote, “What moulting is to birds, the time when they change their feathers, that’s adversity or misfortune, hard times, for us human beings. One may remain in this period of moulting, one may also come out of it renewed.”

Van Gogh’s painting Old Man In Sorrow (At Eternity’s Gate) is possibly the most intense depiction of misery ever painted. In a letter from 1882 he wrote, “I do not wish to express in my landscapes a kind of sentimental sadness, but a tragic grief.” This grief engulfed his life. The fact he completed 900 paintings in his lifetime is a near-miracle. But his creative output didn’t cure his ills. He sold only one painting in his life and in 1890, at the age of 37, he committed suicide by shooting himself in the chest.

I agree there’s value in melancholy. Wistful periods allow you to mine your subconscious and find the gold that resides within the darkness. Carl Jung referred to our shadow side that holds a seed of creativity. Tapping this resource can yield greater awareness, compassion and artistic output. But melancholia can become a self-fulfilling trap. To believe you must feel pain in order to create is to play with fire. You build resistance and must summon deeper reserves of agony to stimulate the creative process.

It’s easy to forget the muse can take many forms. This includes desperation and inspiration. Van Gogh battled poverty, suffered from mental illness, quarreled with family and was spurned by potential lovers. He put his faith in difficulty believing it was necessary to fuel his art. He wrote, “One who has been rolling along for ages as if tossed on a stormy sea arrives at his destination at last; one who has seemed good for nothing, incapable of filling any position, any role, finds one in the end and shows himself entirely different from what he had seemed at first sight.”

Van Gogh would ultimately reach land as an artist. But his journey helped fuel a false narrative that artists must suffer to create. Historians have long theorized that Van Gogh’s psychological and emotional troubles fueled his creativity. In my mind, his depression enslaved him and prevented him from achieving even greater success. He remains a mentor for me, but he’s become a cautionary tale. As Jack Kerouac wrote in the novel The Subterraneans, “I would have preferred the happy man to the unhappy poems he’s left us.”