In putting together my third and final piece showing scenes from long ago Queens, I was reminded of the work of photographers and journalists Percy Loomis Sperr and Eugene Armbruster. Neither are household names, nor have they been celebrated and chronicled in the way that other photographers working in New York City in the early 20th century have been, such as, say, Berenice Abbott; Abbott had already had a celebrated career in photography and studied under the French master Eugene Atget long before she visited NYC neighborhoods and obtained the photos that wound up in her opus Changing New York.

Sperr and Armbruster worked mainly as amateurs. Sperr was an Ohio journalist who turned to photography and Armbruster was an immigrant from Germany who, after arriving in NYC in 1882, proceeded to take thousands of photographs documenting NYC until his death in 1943, and also published several books chronicling neighborhood histories in Brooklyn and Long Island.

While volunteering for the Greater Astoria Historical Society, I was scanning and labeling thousands of postcard views. Most, but not all, of the postcards show well-known structures and parks, including plenty of scenes of vanished beer gardens, amusement parks, and beach areas. Sperr and Armbruster, who photographed their fair share of say, the Manhattan skyline and the Statue of Liberty, also photographed totally mundane scenes, like shacks in Sunnyside and open fields in Bellerose, where row upon row of tract housing would soon appear. Both photographers seemed to recognize that in future decades, there would be great interest in seeing what neighborhoods looked like in the past. Because of this, I like to model my own website (which just celebrated its 18th birthday) after the work of these photographers, and I hope my work will be compared favorably toward theirs.

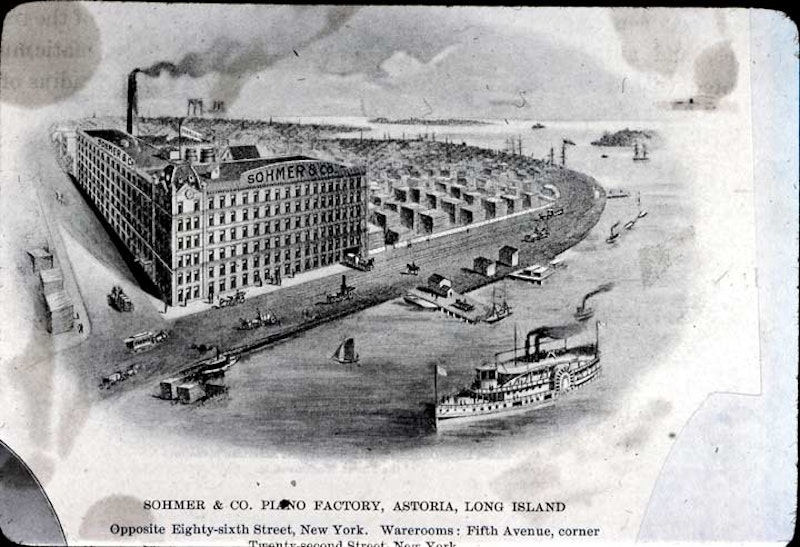

The image at the top of the page depicts a structure that remains in position today. I first encountered the brick Sohmer Piano factory on Vernon Boulevard and 31st Drive, constructed in 1886, several years ago when it was still occupied by the Adirondack Chair Company, and spoke with John Pupa, then Vice President of Operations. Including other details, he mentioned that Adirondack no longer heated the building with coal, but it still maintained its old Hewes and Phillips coal-burning oven, which he showed me, and still took coal deliveries.

The Sohmer building is not the only piano factory converted to luxury in NYC of late—I was taken by surprise to discover that the fortress-like, hulking Steinway factory on Ditmars Boulevard and 45th Street in Astoria became the Pistilli Grand Manor, and the clock-towered Estey Piano building in the Bronx’ Mott Haven became residential in the early 2000s.

Sohmer is still in business, but its pianos are built in South Korea.

This hulking structure, since rehabilitated into the New York Presbyterian Church, a Korean congregation on 37th Avenue and 42nd Street along the LIRR tracks in Sunnyside, was actually once voted the Most Beautiful Building in Queens by the Queens Chamber of Commerce. The 1936 Kinckerbocker Laundry was an example of an exaggerated streamline design, a side category of Art Deco called Streamline Moderne.

Naarden Fragrances later occupied the structure until 1986 when it began a slow slide into utter oblivion and disrepair, which is how I encountered it in 1993 when I began to take the LIRR to work. A couple of years later the church purchased the building and rehabilitated it, and it looks nothing like it does in this photo; all its Deco touches have been removed.

In 1913, the Queensboro Bridge had recently opened, but Queens Boulevard, then called Thomson Avenue, was still largely a wasteland as it ran past 39th Street, then called Harold Avenue. The concrete viaduct that would carry the Flushing Line down the middle of Queens Boulevard was in the planning stages, but construction had not begun yet. After it was completed and opened for business in April of 1917 it ran through Sunnyside mostly unattended by buildings or homes for its first year or so.

Here’s the same scene approximately 60 years later, in 1974. The IRT viaduct has been completed and this is now a major artery through Sunnyside, Queens. In the early 2000s, the masonry arch and terra cotta, which had deteriorated to a sorry state, were given a thorough cleaning and the elevated stations were restored to peak condition. Unfortunately, the MTA replaced the tracks on the viaduct before realizing the roadbed needed to be replaced. The new tracks were duly removed and the trackbed replaced, adding more months of inconvenience for area commuters.

Orlando Potter’s New York Architectural Terra Cotta Company was in operation on Vernon Boulevard and 43rd Avenue from 1886 to 1932. It was the first, and for a long time, the only such company in the city, and supplied terra cotta for over 2,000 projects across the U.S. and Canada, including Carnegie Hall, the Ansonia Hotel, and the Plaza Hotel. Terra cotta is treated clay that can be molded and colored for decorative use in architecture.

The company office building on Vernon Boulevard south of the Queensboro Bridge is all that is left of the works. It was designed by Francis Kimball, who pioneered the use of ornamental terra cotta and was meant to be an advertisement for the company’s products. After the business went under in 1932 the building was abandoned for decades, but did obtain Landmarks Preservation Commission protection in 1982. In 2000, Silvercup Studios purchased and restored it.

Before consolidating with NYC and for several years after that, Queens was made up of small towns with acres of farmland and countryside in between. This photo represents that state of affairs.

Trotting Course Lane, so called because it led to some race courses in Woodhaven, here crosses the LIRR Montauk Branch, which was then at grade. Today, we know Trotting Course Lane as the pedal-to-the-metal Woodhaven Boulevard, which was bridged over the freight railroad several decades ago.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens.