I wasn't born in Queens, but rather at Maimonides Hospital in Brooklyn’s Borough Park. I resided in Bay Ridge for my first 35 years, into the 1990s. Since then, initially to get closer to a job in Port Washington, I have lived in Queens, first in eastern Flushing and then in Little Neck; jobs have come and gone since, but I'm now a block away from the Long Island Rail Road and easy, if expensive, access to Manhattan is simple. Yet I don’t consider myself a Brooklyn or Queens resident. I am comfortable in all neighborhoods, yet have adopted an objective independence from the neighborhoods I find myself in as a result of my work for Forgotten New York.

As a matter of fact, I don’t even consider myself a classic New Yorker in the strictest sense, even though I have lived within its political borders my entire life, and do not conform to the mores and habits that traditional New Yorkers are supposed to have, such as talking a certain way with particular vocalizations, walking quickly, or hewing to a specific political viewpoint. I daresay that had I been born anywhere else, my own particular temperament would had led me to explore its particular modern-day quirks for signs of the past. Had I been born in St. Louis, Nome, or Walla Walla there would have been “Forgotten” websites about them. I even embarked on a Forgotten Boston site some years ago, but have found it hard to sustain since I rarely have the time or money to travel there as regularly as I used to. I’m much more “Forgotten” than “New Yorker.”

My website Forgotten New York, and the book that came out in 2006, is mostly about New York City today, while describing unusual sights or remnants of the past that can still be seen if you're paying attention (or know where to look). For my other book that came out in 2013, Forgotten Queens, I took a different tack and looked into photographs of the past, from about 1920 to 1950, in my adopted borough. Sometimes the reverse of my original game plan made itself apparent, wherein some of these old photos I see the seedbeds of what can be found in the same depicted spots today.

For Splice Today I’ll be showing some Forgotten Queens items that didn’t make the cut.

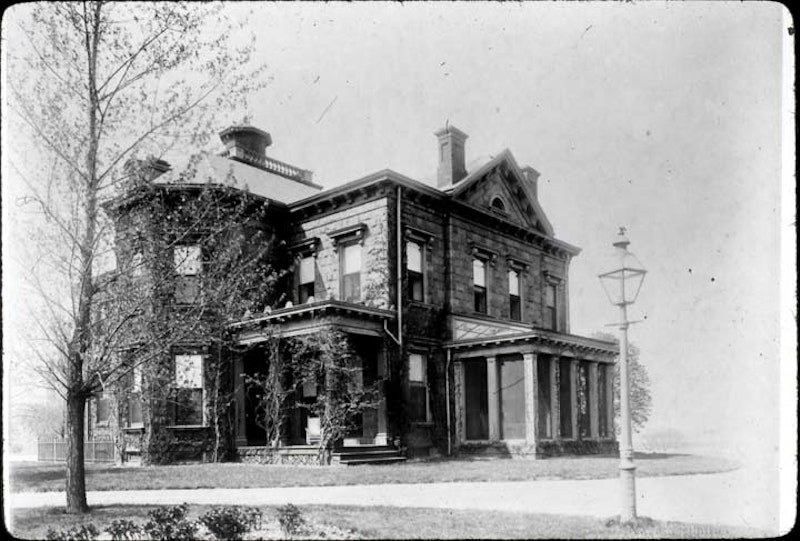

The mansion—shown at the top of this article—on 41st Street between 19th Avenue and Berrian Boulevard, down the block from a present day sewage treatment plant but in hailing distance from the present day Steinway piano factory, was built as a country home for optician Dr. Benjamin Pike in 1856, and was occupied by Pike’s widow for 10 years after his death in 1864. In 1874, William Steinway, who was running the piano manufacturing business, having newly established it with his father and brothers in Astoria a few years earlier, purchased the mansion.

The Steinway family owned the mansion for the next fifty years, until selling to Turkish immigrant Jack Halberian, who divided it into boarding rooms for renters. Jack’s son, Michael, inherited the house and partially restored it to former magnificence. Michael passed away in early 2011, and his heirs did not feel confident they could maintain the 27-room mansion, and subsequently put it on the market. It sold for $2.6 million to mystery investors who have since surrounded it with mixed-use commercial buildings on its 42nd Street side. In 2014, the east side of the magnificent building was open to view after its high hedges were cut down, but the view was quickly blocked again by low-rise buildings.

Gantry State Park is located in a recent development at water's edge known as Queens West. It makes a handsome riverside addition to New York City, which has shamelessly left undeveloped an incredibly large volume of waterside property which really should be available to the public as parkland.

Barge transfer gantries as seen from the new East River pier. Goods were floated across the river on barges, and transferred to a spur of the Long Island Rail Road at water's edge in Hunter's Point. When the park was built, the designers placed railroad tracks in the same spot where they used to run to the waters’ edge.

The Queens waterfront looked forlorn when the photo was taken in the 1970s, and it still was largely in this condition when I encountered it in the mid-1990s.

The LIRR spur can still be seen in several spots. It runs just south of 48th Avenue from Jackson Avenue west to the waterfront. From Jackson Avenue to Vernon Boulevard, it is a garbage-strewn lot, but from Vernon Boulevard west to the waterfront it is a playground as well as Gantry State Park at its western edge. By June 2003, the spur seen here had been completely filled in and was no longer visible.

Just about everything seen in this photo, with the exception of the smokestacks, is still in existence, though in altered form.

If the Citibank tower on Jackson Avenue is Long Island’s most recognizable landmark, the four ebony smokestacks of the Pennsylvania Railroad Powerhouse on 2nd Street and 51st Avenue marked Hunter's Point with an indelible stamp. The big building with its tall arched windows and massive granite base was built by McKim, Mead & White beginning in 1903 and was completed in 1909, the year before the firm finished Manhattan’s classic Pennsylvania Station. (Some scholars believe Westinghouse, Church, Kerr & Co., the firm that handled Penn Station’s mechanical and electrical systems, actually designed the building.) The smokestacks appear in art by Georgia O’Keeffe.

The Powerhouse burned coal to boil water for steam to drive the turbines (only the second in the country to do so). By 1910 it contained five generators using between 5,500 to 8,000 kilowatts. In 1959, Schwartz Chemical Company moved into the Powerhouse and it has seen mixed use in the ensuing years; for a time it was an indoor tennis court. CGS Builders purchased the building and converted it to residential use approximately 10 years ago.

The building in the foreground is the old Waterfront Crabhouse, opened by boxing promoter Tony Mazzarella in 1978 in what had been Tony Miller’s waterfront hotel, a 19th century watering hole at what had been the Long Island Rail Road’s western terminus until 1910. The original Crabhouse closed in 2015 after Mazzarella’s death, but has reopened under new management.

Sometimes called Queens’ answer to the Flatiron Building, this former showroom for L. Gally Furniture is still standing where 21st Street, Astoria Blvd., and 27th Avenue come together. Its corner onion dome is still in place too.

In 1912, L. Gally ran ads for a special spring sale of "high-grade" furniture. Three piece parlor suite, with mahogany finished birch arms and backs, had carved steel springs, and fine quality velour upholstery and sold for only $16 (or 50 cents a week). Polished oak sideboards with several drawers and brass trimmings and mirror could be had for only $10.50. Brass beds went for $9.50, solid oak couches for $6.50 and oak chairs for as little as 95 cents.

Operating from the west end of today’s Astoria Boulevard between 1843 and 1918 in Hallets Point, the 92nd Street Ferry was founded by Astoria Village developer, fur merchant Stephen Ailing Halsey.

Astoria’s pedigree dates to the mid-1600s, when William Hallett received a grant for the area surrounding what is now Hallett’s Cove by New Netherland director general Peter Stuyvesant. However, the oldest structures in the region date to the mid-1800s, Halsey had incorporated the village in 1839.

Astoria was named for a man who apparently never set foot in it. A bitter battle for naming the village was finally won by supporters and friends of John Jacob Astor (1763-1848). Astor, entrepreneur and real estate tycoon, had become the wealthiest man in America by 1840 with a net worth of over $40 million. As it turns out, Astor did live in “Astoria”–his summer home, built on what is now East 87th Street near York Avenue—from which he could see the new Long Island Village named for him.

No sign that there ever was a ferry remains at the west end of Astoria Boulevard; indeed, that section of the boulevard has been a dead end since the construction of the Astoria Houses in the 1950s.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens.