I worked at a small design firm copy editing and proofreading financial PowerPoint slides from May through August 2019 at 1740 Broadway, the “MONY, MONY” building near Columbus Circle. I had an hour for lunch, so I roved about as far north as 72nd St. and as far south as Duffy Square. One of my walks brought me past Lincoln Center, at Broadway, Columbus Ave. and W. 65th St. It got me thinking about a trio of long-gone artifacts in the area that I discovered from 1999-2002, in the early years of FNY.

A teardown on the northwest corner of Broadway and W. 64th revealed this huge ad for Hunter’s Baltimore Rye in 2002. The liquor was first distributed in Baltimore in 1860 by William Lanahan. The brand had aristocratic pretensions: The label and ads featured a man dressed in foxhunting garb astride a horse set to gallop with the hounds. It made the Lanahan family rich and Hunter Baltimore Rye was a popular brand of rye whiskey until the 1940s. The Hunter Rye ad was painted on the side of the former Liberty Warehouse, which had a painted ad of its own above the whiskey ad. The Liberty Warehouse, which was built around 1902 (about the same time the ad was painted on the side of the building facing Broadway, also featured a 37-foot tall replica of the Statue of Liberty). When the old warehouse was converted to residential, Liberty was packed off to the Brooklyn Museum, which put her in the parking lot. These days, Liberty is at the National Building Arts Center in Sauget, Missouri for repairs and a permanent home.

This mélange of painted ads could be seen on the buildings facing W. 66th St. between Broadway and Columbus Ave. The buildings are still in place, as are presumably the ads, but they’re now obscured by another high-rise with a Century 21 store on the ground floor.

Omega Oil was an all-purpose liniment sold in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. Colorful painted ads for the brand can still be found around town, but fewer in number. Columbia was a very old brand—I found an ad for Columbia Soup in a Harper’s from 1894. While this batch of Omega Oil ads is now obscured, a wall full of them can be seen facing an NYPD precinct parking lot on W. 147th St. east of Frederick Douglass Blvd.

Besides 100 W. 33rd St. itself, which faces 6th Ave. between W. 32nd and W. 33rd Sts., the only tangible remnant of the Gimbel Brothers Department Store is this vertical painted sign that can be seen as you’re traveling east at #119 W. 31st St., a block away from the store. The Gimbel Brothers chain of department stores didn’t originate in NYC and existed for over 60 years before arriving here. An immigrant entrepreneur from Bavaria, Adam Gimbel, opened a dry goods store in Vincennes, Indiana in 1842 and later expanded to Milwaukee and Philadelphia. The Gimbels commissioned architect Daniel Burnham to design its NYC flagship store in 1910. Gimbels was so successful it later acquired rivals such as Saks and Schuster’s and by mid-century, it was one of the two Midtown department store titans along with R.H. Macy, a block away on W. 34th St.

After Gimbels succumbed to competition and closed in 1986 (rival Orbach’s closed around the same time) 100 W. 33rd, on 6th Ave. directly across from Herald Square, was converted into the Manhattan Mall in 1989. I considered the Manhattan Mall a modern marvel as its interior was hollowed out and you could look up and see seven floors all containing stores, with access by escalators and glass-walled elevators. The food court was on the seventh floor, and if I was lucky I could sit by one of the huge windows during lunch and look up and down 6th Ave. This configuration, though, was considered too good for the hoi polloi and after JC Penney took over as the mall flagship from A&S, the food court was relocated to the basement. Today there are no stores in the “mall” at all, as it serves as office space, and Macy’s greatest rival is now represented by a painted ad.

It’s merely a coincidence—etymologically it’s completely unrelated—but I like the way the name “Noyes” combines the negative and the affirmative in one name. Undoubtedly, the thousands who possess the name aren’t all moderates or wishy-washy. It’s more likely just the opposite. And here’s one of the highest painted ads you’re likely to see, on the 16th and 17th floors of the Pennsylvania Building, facing the east on W. 34th St. between 7th and 8th Aves. The Charles Floyd Noyes Company managed the Pennsylvania Building from 1951-1980. Noyes was known as “The Dean of Real Estate.” It’s likely his name will remain visible high over W. 34th St. for many more years, as this Mack billboard ad gets full sun in the morning but has remained stubbornly clear. The Pennsylvania Building was built in 1925, but it’s the sign was probably painted in 1951 or a couple of years after that.

Hungarian immigrant Alexander Samuel Beck opened a shoe store with his brother Samuel on Fulton Street in Brooklyn in 1909. After the partnership with his brother dissolved he opened a more successful store on Manhattan Ave. in Greenpoint in 1914, and Beck was able to expand. After a sale to Saul Schiff in 1945 there were 147 stores in the East, Midwest and South, with as many as 18 stores in Manhattan. Business declined after that, and the store this sign illustrates was the last one remaining in Manhattan at #128 W, 34th, across the street from Macy’s, when it closed in 1982. Subsequent owners have found it too expensive to remove, and thus the Deco-y sign’s a reminder of an age when people wore shoes other than sneakers.

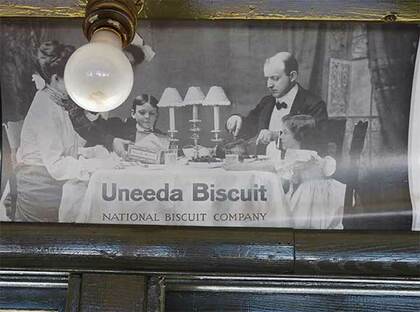

The National Biscuit Company was formed in 1898 by a merger of the Midwest American Bakeries and the eastern New York Biscuit Company, while these companies, in turn, had been formed by mergers of much smaller local bakery firms. The next year Nabisco, controlled hundreds of bakeries and reported an income of $55 million annually. Nabisco then launched its first national product, a soda cracker, and contracted ad giant N.W. Ayer to devise a name and a campaign, and the era’s Don Drapers arrived at the punny “Uneeda.”

At the same time, cardboard packaging and wax paper wrapping was catching on, instead of the previous methods of cracker barrels and crates. Bread products could be moved to store shelves easily and protected from spoilage. Ayer devised ads featuring the “Uneeda Boy,” clutching a box of Uneeda in various scenarios. Even the streamlined sanserif lettering on the package and the ads pointed toward a mid-20th Century esthetic.

Nabisco also delved into the billboard and painted ad method of advertising, pasting the distinctive Uneeda Biscuit lettering on thousands of buildings. Like Fletcher’s Castoria painted ads, many of them have held on to this day. In subsequent years Nabisco devised dozens of popular crackers and cookies, such as Oreo in 1912, still the USA’s most popular cookie brand. Nabisco merged with Standard Brands in 1981 and was purchased by RJ Reynolds in 1985, creating a snack food monopoly that also included Planters’ Nuts and Life Savers. Uneeda’s sales had decreased and it was far from its early eminence as the star of the brand, and Uneeda was discontinued in 2008.

This Uneeda ad portrays a typical home life tableau in what looks like the 1910s. Dad, carving up a roast chicken, is wearing the detachable collar of the era, likely an Arrow. The lightbulb (aboard one of the ancient subway cars the Transit Museum trots out a few times a year) is blocking the maid, who’s just cracked open a box of Uneeda. I’ve thought the sanserif Uneeda logotype was ahead of its time, as sanserif fonts didn’t become popular until the 1920s with fonts like Futura. Helvetica followed in 1957 and conquered the world.

I haven’t had an orange soda in years, although I’m a dedicated Diet Coke drinker. Orange Crush is probably the most popular orange soda in the USA, though in NYC I remember Hoffman as my prime source back when I drank soda as a kid. The company originated in 1916 as Ward’s Orange Crush and the Crush brand has also been appended to dozens of other flavors. Clayton J. Howel, president and founder of the Orange Crush Company, partnered with Neil C. Ward, who originated the recipe that at first included orange pulp, which has long since disappeared. The Crush company has been owned by Proctor and Gamble, Schweppes and currently, by Dr. Pepper (one of the sodas whose taste I actively dislike). Originally, I thought the name “crush” came from the sound made by clinking ice cubes in a glass full of the stuff but it actually refers to crushing oranges and other fruits to acquire the pulp.

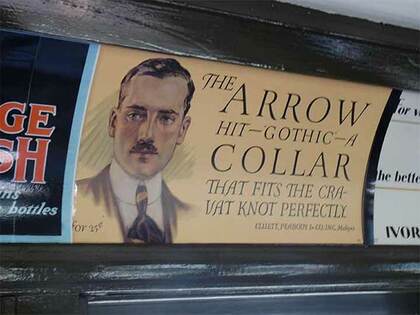

You might remember Arrow as a shirt manufacturer but this ad is specifically for shirt collars. Before the 1930s, shirts came without collars and detachable collars were sold and you had to buy both shirts and collars; it got easier after that when shirts were manufactured with the collars stitched on. Cluett, Peabody & Co. of Troy, NY were originally collar manufacturers and created the Arrow brand of detachable shirt collars. According to the Free Dictionary, “About 1905 the company began an advertising campaign that featured an idyllic young man wearing an Arrow shirt with the detached collar… Hundreds of printed advertisements were produced from 1907 to 1930 featuring the Arrow Collar Man. The fictional Arrow collar man became an icon and by 1920 received more than 17 thousand fan letters a day.”

I have a personal connection to Cluett-Peabody because for many years, both my mother Betty and grandmother B. worked in its office in Troy.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)