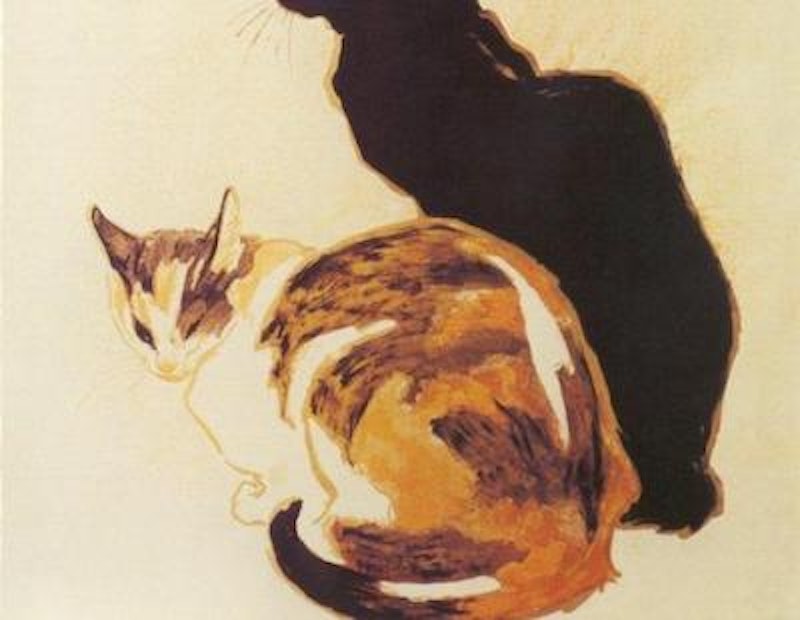

Minerva was a tortoiseshell cat; a furry swirl of black, brown, orange, tan, and white, with a heart-shaped face, clear, green eyes, and a direct, honest gaze. If you’ve seen the fin-de-siècle advertising posters of Théophile Steinlen, you’ve seen Minerva.

One day, Mimi showed me an online animal adoption site. One cat had a sweet face, beautiful eyes, and uncommon markings. I followed up. There followed a succession of telephone calls. We learned that the cat was about two years old. She’d walked from the mists of history about a year before when she mewed at someone on a Manhattan street. Now being introduced, the fellow picked her up and, though unable to keep her, introduced her to what British writer James Harding called that “…freemasonry that links animal lovers.” She went through several households, largely because, though sweet-natured and affectionate, she was emotionally needy with an understandable separation anxiety. In short, the would-be adopters lacked patience with her constant demands for attention.

Anyway, the cat arrived. She left the carrying case and, curious, came over to us. We picked her up and stroked her. She purred and snuggled into our laps. The foster parent who brought her to us told us the cat was named Hope. The door had barely closed behind her when I renamed her Minerva, after the Roman Goddess of Wisdom.

Mimi noted that, from the beginning, we often talked about little else than the cat and her behavior: that we were sounding like first-time parents, and doting parents of the sort for whom we’d felt little sympathy.

We were pleased and surprised at how gentle Minerva was and how she trusted us. She was never aggressive or menacing. Even the need for attention diminished as, we think, she realized over time that she’d come to what pet lovers call a forever home.

After a few weeks, she regularly joined us in bed, strolling over the counterpane to gaze in our faces, sometimes at a distance of an inch and a half. After a few minutes’ stroking, she began lying on her back in an abandoned pose. I’d stroke her tummy and she’d close her eyes, purr very loudly, and rhythmically extend and retract her claws. I went online to find out what this meant: she was happy, she trusted us.

She was always chatty, making sure we knew she was present. Once she’d come to understand life in our household, Minerva woke me every morning between 5:00 and 5:30 to remind me to refill the food bowls. She mewed softly, touched my chin with her paw, and purred once I awoke and petted her. When the weather grew warmer, she began jumping onto the table in the sun room, gazing thoughtfully at the squirrels and birds in the back yard. It’s not that she’d catch them. As wisdom incarnate, Minerva understood the journey—the chase—and not the arrival matters. One April morning, as we began cleaning and replanting the garden, she slipped through the open door to recline on a sunlit bench, peacefully surveying her new realm.

Thereafter, once there was light in the sky, after she’d had breakfast, she’d insist that we crack the back door so she could go out and play.

Within a few weeks, she added her routines to ours, so they never seemed an extraordinary imposition. She daily joined Mimi on the chaise longue. She might climb onto Mimi’s torso, gazing into her face, rubbing her face against Mimi’s, and purring as she was petted. Just as often, she might settle down on the chaise, just out of reach, as if to test Mimi’s affection: if you love me, you’ll inconvenience yourself by sitting up so you may pet me.

As for me, at least once a day she’d quietly enter my office, where I’d be typing, place her forepaws on my thigh, look into my face, receive the invitation, and vault into my lap. When I was truly busy—not all that often—she’d then glance down, a little disappointed, and walk away.

She showed intuition: when we were sad, she’d climb into our laps to comfort us with head bumps and purrs.

So she became a quiet and essential part of our lives.

There were few dramas, though she always intuited when we meant to take her to the veterinarian and disappeared into a closet or under the bed.

And, as cats are like potato chips, we couldn’t have just one. Minerva gave us three kittens. We had understood that cats preferred to go off alone to bear their young. Not our girl: when she felt the moment had come, she ran to me, demanded attention, and then headed for her basket. I called for Mimi. Once we were there, as she began trembling, we stroked her, talking to her as soothingly as we could. Animals may not understand one’s words, but they appreciate the tone of one’s voice and understand the speaker’s emotions. Anyway, Minerva built up to a very loud yowl, and then out popped Rosalind. Two yowls later, we had Imogen and Sebastian. She then went to work, grooming her young. She was a good mother and, at least once a day, she brought them all, one at a time, onto our bed.

A week or two after they were weaned, she was neutered, which calmed her. With time, she became august and dignified. She gained weight during her pregnancy and never quite lost it, usually weighing between 14 and 16 pounds, and remained slightly distended on the side where she’d nursed the kittens. I became conscious of her weight when, while trying to put her in a cat carrier for a visit to the vet, she wriggled from my grasp as I somehow tripped and fell to the floor. She came down decisively on my nose. That visit was rescheduled.

When the little ones were old enough, we had them neutered, too, and so there were no more misadventures or unexpected kittens, at least from our cats. Like their mother, they too came and went as they pleased, returning for lunch, a snooze, or as the sun settled in the West.

She never clawed or bit any human being. Yet, when a feral male cat whom we believed to be the kittens’ father returned to the yard to attack them, as feral fathers will, she leapt from the back stairs at full gallop, battered him with a lightning succession of clawed cuffs, and drove him from the yard. Triumphant, she returned to the sun room table from which I’d watched all this, looked me in the eye to reassure herself that I’d seen her performance, and began pulling tufts of his gray fur from her claws.

She moved with us in early 2016 to Antrim, New Hampshire, and we were looking forward to much more time with her. Indoor-outdoor cats in rural New Hampshire face problems they didn’t in Bay Ridge, particularly the predators: coyotes, wolves, and fishers. But Minerva only went out for an hour or so in the morning, to sun herself on a stone wall with her children, and soon returned.

As the summer of 2016 turned to autumn, Minerva began losing weight, her face and eyes coming to dominate her appearance as they had not before. At first, this didn’t concern us. She’d been fat since she bore her kittens, sometimes resembling nothing so much as a furry football with long legs. Probably, part of her impact when she attacked the kittens’ father had simply been inertia. Once, when a veterinarian asked me what she liked to eat, I replied, “Food.” Our move to New Hampshire in early 2016 had been healthy for all of us by reducing the stress of daily life. We owned our home: solving the problems was now our responsibility and we enjoyed doing that. We thought a quieter life might be doing the same for her.

One morning, I noticed that she was no longer slender but gaunt. I could feel her ribs and vertebrae when I stroked her. Later that day, I petted her two surviving kittens. Both are slender and active: neither felt bony along the vertebrae.

So I took Minerva to the Henniker Veterinary Hospital, some 10 miles away, for a complete checkup. They examined her and, after firmly examining her abdomen, kept her overnight for further examination. Then they told me she had two inoperable tumors in her abdomen, pressing on her stomach and her liver. They recommended that we take Minerva home, watch her closely, and when it was time, return with her.

It took some time to put the car in drive as I couldn’t see for the tears. I despaired, not least because I loved this cat more than I do many human beings.

She remained with us a little longer. Once home, she enjoyed all the treats and special things that she liked and some new things, such as prescription cat food and complete attention whenever she seemed to want it. She often crept out to the sun room to see Mimi, who now picked her up to the chaise longue because Minerva could no longer climb up.

When Minerva stopped going upstairs to wake me, I brought her upstairs once a day that I might stroke and groom her. She now rested while I did this, purring loudly, but without the energy to roll over so I might rub her tummy. When she wanted to leave, she found her way downstairs, taking the first few steps on her own and the remainder with some help from gravity.

The other cats deferred to her. Her son, Sebastian, the Black Prince, would nuzzle her and ensure that she had first place at the food bowls while she ate, waiting until she was done to feed himself.

Only on the night of Tuesday, January 3, when she was in a distress we could not alleviate, did we decide to take her back to Henniker. She was so weak that I felt we could carry her in a basket rather than have her endure the indignity of a cat carrier. As I walked with her to the car, she leapt down and ran, as she always had when she sensed that I wanted to take her to the vet. This time, she went only 20 feet. Then she stopped, exhausted. I picked her up as gently and carefully as I could, kissed her, and whispered, “If you have a soul, and I believe you do, please remember that you were our first—we chose you first—and we have always loved you.”

Minerva then reclined in the basket, swaddled in her blanket, and raised her head as we went down the driveway. She gazed steadily out the windows at our house, our barn, our trees, and our land, and then at the mountains of New Hampshire, where nearly every vista is beautiful, sometimes turning her head to follow some moving object. I remembered a once-famed injunction on an old English tombstone:

The wonder of the world,

The beauty and the power,

The shapes of things,

Their colours, lights, and shades,

These I saw.

Look ye also while life lasts.

Then we were shown to a small room, where we placed her basket on a table and, after the doctor had gently done his work, stroked her as she fell asleep and her heart stopped.

In the spring of 2017, when the ground had softened, I dug her grave in our garden. We buried her in one of Mimi’s elegant hatboxes, lined with Minerva’s favorite blanket. For the journey, we packed a catnip toy (she only played with them when she thought we weren’t looking; she may have felt too dignified to play in public), two shiny pennies for Charon, the ferryman at the River Styx (she was, after all, named for a Roman goddess), and an egg, which is a symbol of life.

Besides, she loved egg yolk, as I had learned one morning while preparing scrambled eggs.

During early 2018, I commissioned a granite marker from Peterborough Marble and Granite Works for her. They installed it during the summer.

MINERVA

2008 – JAN. 4, 2018

BELOVED FRIEND

I pray that Minerva will not be denied in Heaven the soul she had on earth. We hope to meet her again in that place where all of God’s creatures understand one another through love, which transcends the limits of earthly language and reason.