Movie stars have momentarily taken the focus of Americans otherwise preoccupied with “watching the war,” and even if no one saw King Richard, everyone still knows who Will Smith and Chris Rock are. Say what you will about the state of the film business, Hollywood and worldwide, but the public is still captivated by actors, with the same identification they’ve had since turn-of-the-century silent serials. Novels, on the other hand, only had a brief grip on pop culture, for a few decades in the middle of the 20th century, strictly post-war through the 1980s. By the time of Y2K, David Foster Wallace regularly grieved fiction’s diminished place in American pop culture, particularly in the face of television. But writers like Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal, Tom Wolfe, Philip Roth, Don DeLillo, or Truman Capote only appeared on television for a few decades, and in the last 30 years, there have only been two literary phenomena: Harry Potter and 50 Shades of Grey. The former keeps shrinking in stature due to its whacked-out author, and while the designation is shaky in both cases, I can’t bring myself to call 50 Shades “literary.”

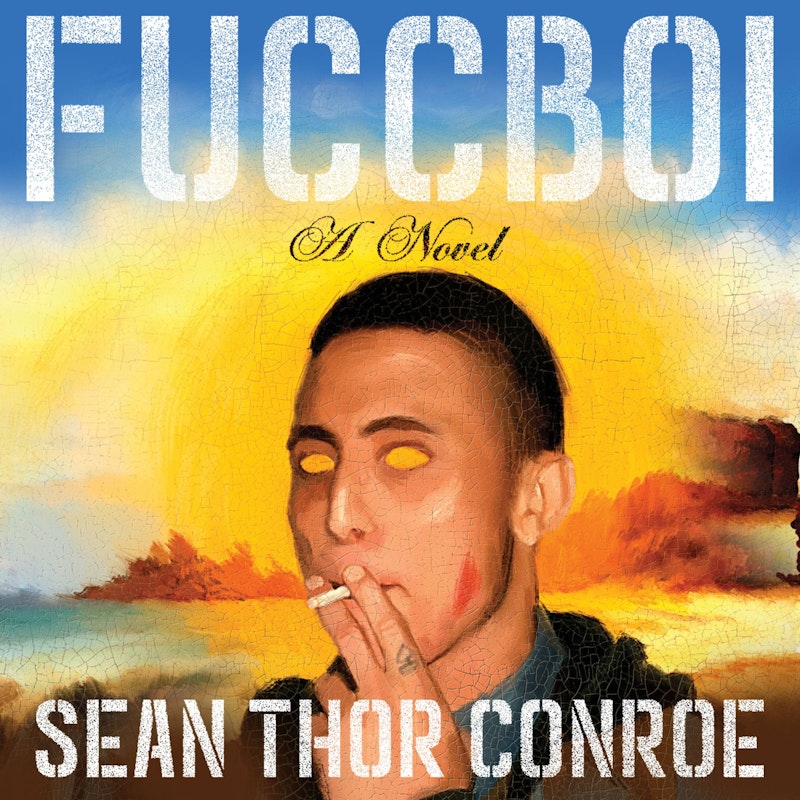

There are successful books and authors, mostly women: Sally Rooney, Ottessa Moshfegh, Nico Walker, Torrey Peters. Of them all, only Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation has entered the lexicon in the same way that Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities did in the late-1980s, or Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho in 1991. Sean Thor Conroe writes in his debut novel Fuccboi that he “wants to write books for people who don’t read.” And his book reads like it—not a diss at all, but Fuccboi is the kind of novel that would thrive if our culture were interested in reading. The culture wouldn’t have to be different at all, especially because this is a book of the moment, and there’s no formal or stylistic impediments to broad appeal. People just don’t read as much anymore.

Conroe’s protagonist is, like all of Tao Lin’s, a barely-veiled version of himself, but with differences, embellishments, and stark departures. Fuccboi follows Sean, a gig worker in Philadelphia hung up on “ex bae,” and many other “baes” and “bros,” as he works his way through his late-20s. Postmates is a brutal gig, especially when asshole college kids don’t tip—in the snow. Sean—and Conroe—are extremely affable, and the regular use of line breaks and his very informal and unassuming delivery make for the most compelling and endearing man who’s ever been branded a “fuckboy,” by himself or others. The only strain that would suggest anything unusual is Sean’s occasional insistence and stubbornness when it comes to discussions—and arguments—about gender roles and misogyny.

It’s a testament to Conroe’s writing that none of this ever comes off as anything but genuine, warm, and searching—“investigating,” as he stresses. The book ends with him breaking up a domestic dispute on his block, and once the guy beating his wife has driven away, Sean has forgotten all about the stupid gender debate he got into with someone in his head. Fuccboi is a wonderful novel for any fans of Tao Lin, particularly his most recent novel Leave Society. The middle section of Fuccboi follows Sean as he goes through a painful diabetic autoimmune skin disorder: peeling, swelling, pussing, waiting too long to go to the doctor. His recovery is treated seriously but with clear eyes, much like Lin’s search for a healthier, holistic way of living throughout Leave Society.

Conroe’s book is a thoroughly contemporary novel, whereas John Boyne’s The Echo Chamber belongs to an era when millions of people still read 500+ page novels. The Echo Chamber follows the famous Cleverley family, the husband a broadcaster, the wife a beach-read author (all of her books are ghost-written, but she “comes up with the ideas”), the two sons are basket cases in their own way but basically kind-hearted, and the daughter is a social media psycho who in the end gets SWAT’d for making threats from a secret Twitter towards her actual, verified Twitter.

The dad makes several transgender faux-pas with a person working in the building, his mistress gets pregnant, the wife’s lover is seeing the daughter too, and by the end they’ve run themselves into the ground and move to a remote part of Scotland “where they can’t get Wi-Fi.” How serene. I understand phones are addictive, but this shit isn’t heroin. Boyne’s point of view is a bit old-fogey, but his picture of our current chaos is pretty spot-on, especially when it comes to the endings for all of the characters. But his quaint little ending in Scotland, along with all of the extraneous subplots—like the Ukrainian lover—belong to a kind of novel that may still comfort some, but will surprise or excite no one. No art form in this state should settle for popular mediocrity.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith