We enjoy robot apocalypses, but it's hard to take them seriously. The Terminator flicks and their imitators can be a lot of fun, but we have about as much faith in their possibility as a vampire romance or the latest zombie invasion. We’ve seen actual robots, as they exist today, and we deal daily with slow, bug prone, virus-susceptible computers. These things seem purely hypothetical if not fantastical.

Most robocalypses have to do with The Singularity. That's the projected point at which machine intelligence eclipses our own, leading to an outcome that we humans are literally too stupid to figure out. Some scenarios have the robots becoming our new overlords or worse. In the satirical Flight of the Conchords song, "The Humans Are Dead," robots sing of their newly murdered masters, "We used poisonous gasses/and we poisoned their asses." One of our new techno replacements delivers a rocking binary code solo. The Singularity is easy to mock because it sounds to most of us like a geeky version of the Apostle John's more tripped out moments.

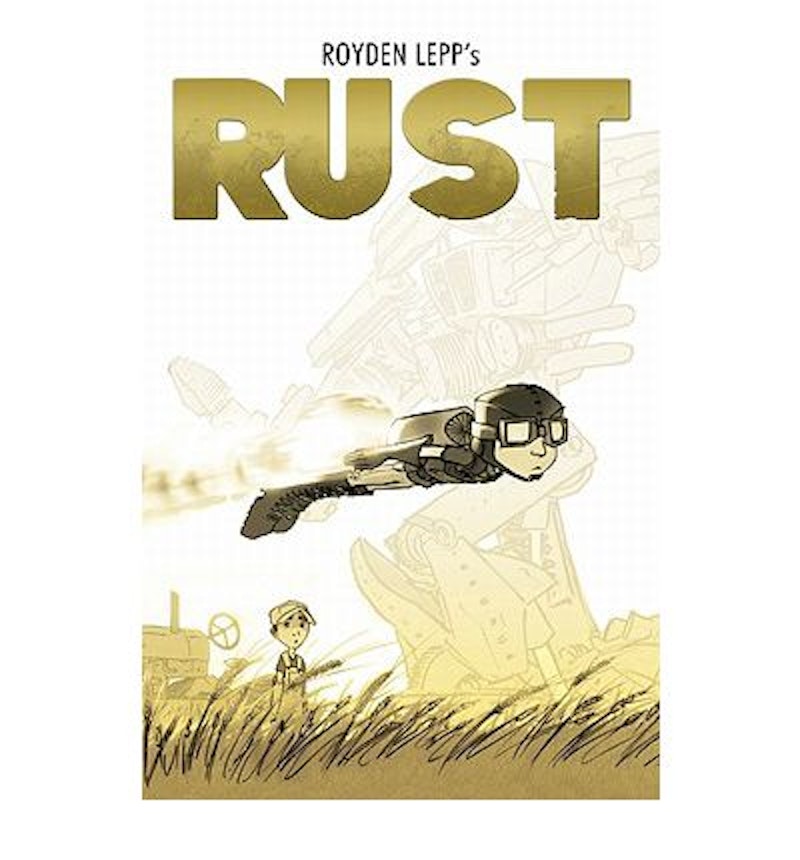

If there is one person who might be able to make me believe in the robocalypse, it's Seattle-based video game animator and comic artist Royden Lepp. In Rust: Visitor in the Field, he certainly manages to suspend my disbelief. The graphic novel begins with a battle scene from "48 years ago." Anglo looking troops advance toward trenches where troops with gas masks (read: Germans, or close equivalents) are dug in. The gas masks in the trenches grab their rifles and start to put down the charge.

Then the robots arrive and go to work. These new steel soldiers are unaffected by bullets or gas, though vulnerable to more serious explosives. Smaller robots on the Anglo side march toward the trenches. The gas masks counter with their own larger, more menacing killing machines. One Anglo soldier on a mysterious salvage mission is nearly killed by these metal monsters. He’s saved by a lightning bolt in human form. Soldiers in modified aviator uniforms with jet packs on their backs enter the fray.

We don't know who that soldier is, or who the jet pack boys are. We start to piece it together slowly as Lepp gives us breadcrumbs. The soldier probably had some relationship with a present day family of farmers called the Taylors. Roman is the oldest son, a strapping dark-haired young man from mid-America (or mid-Canada; Lepp was raised in the prairie provinces) with generic farmer dress: cap, overalls, boots, white t-shirt. He runs the farm and looks after him mom, younger brother Oswalt and kid sister Amy. Their father is elsewhere. Roman's letters-to-Dad serve as our window into the story.

The picture of the future that starts to emerge is a world after the robocalypse, or perhaps smack dab in the middle of one. "We won," says Roman to his kid brother, with no fanfare. He adds optimistically, "After our country built the machines to help us fight, they went a step further. They built machines to fight for us, so we wouldn't have to anymore." But it was a costly victory and one that "we" are still paying for. Two of the three children we meet have serious deformities. Historical knowledge of what happened is spotty, because the government has repressed it.

Roman's neighbor from the next farm over is an aged man who fought in the war as a lieutenant. He’s bound by law from talking about much of what he saw. "It became a war of technology, a war of secrets and lies," he explains anyway in one of those screw-it-I'm-older-than-dirt moments. "The machines were definitely built to replace us. They marched past in silence. Eventually there were no men to be found fighting. Only machines. They didn't need food. They didn't need orders. They didn't need guns." The only thing they needed to do was to kill and destroy the enemy.

After the armistice, many of the robots were scrapped. A few were reprogrammed for civilian work, but that doesn't always work out so well. "Their code breaks down as they get older," says the former lieutenant in a rather-too-benign explanation. For some reason that we are invited to guess at, the whole former robot horde seems bound eventually for the Taylor farm.

Too many battles in movies or comics give readers no help mapping the action. Lepp's background in video games helped him, and us, avoid this pitfall. There is a fog of war for the characters, not the readers. The artwork, black and white with brown and yellow hues, is simple and effective. Lepp's storytelling so far is an achievement. He sets us down with squarely with a few hard bumps in a world that was forever changed the day the robots attacked.

—Jeremy Lott, editor of Real Clear Books and Real Clear Religion, is writing a book about death.