My “customer” is here for us to take pictures of his coronary arteries. He weighs close to 250 pounds and it takes a couple of us to get him on the table. I haul his gut out of the way, secure it with adhesive tape, and scrub the area around his femoral artery, where we’ll gain access to his internals. I feel around the groin and finally locate the artery beneath all his flesh. Then, in goes a fat hollow needle. Blood spurts immediately from the back of the needle. A wire’s inserted down the needle, and the needle’s pulled out over the wire. Now the guy is laying there with a guitar string sticking out of his thigh. Next, I slide a six-French sheath over the wire, withdraw the wire, and leave the sheath in the wire’s old position. That’s as far as they’ll let me go at this stage of my learning. The sheath now supplies a direct pathway to the patient’s coronary arteries. This idea was figured out by a German guy named Werner Forssmann, who tried it out on himself in 1929.

With the sheath in, different types of wires, medications, and catheters can enter directly into the heart. I’m a scrub tech, and keeping the sterile field sterile is my main concern. This includes me, from my elbows down to my hands, and from my waist to my chin. The only sterile area in the room itself is the space in the immediate vicinity of our guy's torso, a volume not much bigger than a beanbag chair.

Sterile is an approach, an intention imposed upon a limited space by the strict regulation of our physical movements. Sterile is a location within a room, but could never be the entire room. There was a time when sterile didn't exist, when doctors operated in top hats and greatcoats, without masks, gloves, or even hand-washing. I’ve seen old pictures with surgeons smoking cigars in the operating room. With a sheath now in place, the patient's blood pressure suddenly appears on one of the monitors. But they’re more than numbers now. There's a waveform rolling across the screen, and every notch and slope and peak and valley in the wave means something. This is the physical shape of the systolic and diastolic pressures changing over time. The cardiologist reads the wave, makes no comments. He’s a conductor reading a score, hearing music in his head.

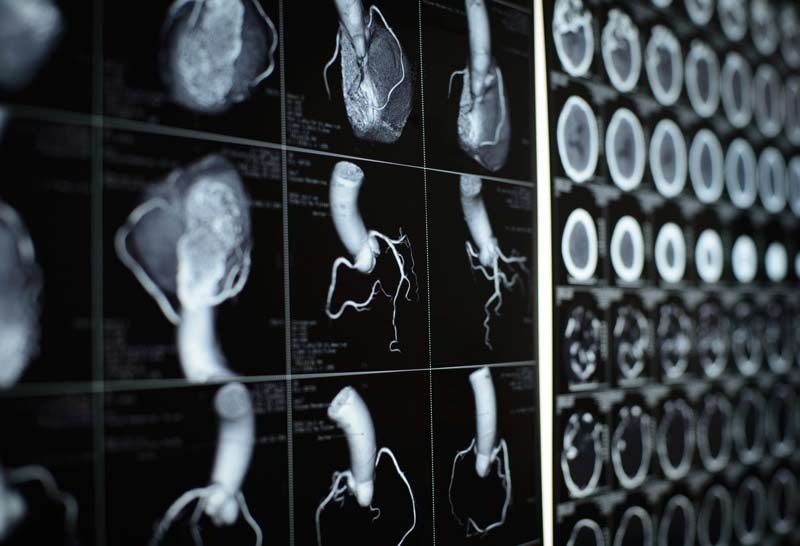

I watch the EKG screen, another pattern of waves, but limited to purely electrical activity. The heart is about 70 percent salt water. Ions like calcium, sodium, and potassium are responsible for the electrical activity that makes up the heart’s contractions. Some current leaks through to the surface of the chest and is recorded on pink graph paper. This is the electrocardiograph, or EKG, and was the first machine since Sputnik to capture my undivided attention. Two coronary arteries leave the bottom of the aorta and send blood to the heart muscle itself. We’ve snaked a JL4 (Judkins left) through the sheath and into the opening of his left coronary artery. The doctor injects contrast dye, which shows up black on the screen, and the arteries take on the aspect of tree roots. This guy’s roots have problems. He has some serious blockages, and some stents will be required.

Keep in mind that the left heart pumps blood to the entire body, and the patient can’t afford to have it not working properly. This guy’s left is mostly blocked and will require a pair of stents. These come on the end of a balloon catheter, and I’ll inflate the balloon to the required number of atmospheres needed to expand them.

After we’re done, I roll the patient into the recovery room. I need to hold pressure on the site where we went into the femoral artery until the pinhole closes up, usually about 20 minutes. But this patient is so fat that it’s difficult for me to find the exact spot. The pulses in his feet are okay, so I know blood’s getting through. The monitor signs look okay, good oxygen sat and a normal EKG. I send him upstairs to the overnight floor. I’ll soon learn to watch the patient, not the monitors.

“Z-man, better get back to your room.” And here my troubles began. My patient is back in the lab. He looks like shit. His heart is stopping and starting. I think he might be bleeding out internally, and the outcome would be completely negative. Blood exiting the circulatory system is never a positive. The truth is, this patient will probably die of heart disease. That’s why he’s here, in this room, on our table: to assess his future, and add to it if possible. I take it for granted that some patients will die. Humans are a system composed of numerous sub-systems, each sending signals to the others with inconceivable rapidity. An infinity of cellular and molecular call-and-responses, ions passing in and out of cells. The entire process intoxicates me. We are living bags of chemicals. The number of things that can go wrong within a heart is astounding, and I can't help myself. The more disease the patient comes in with, the better I feel.

His heart is giving out, and it’s time for the paddles. The windows between the rooms fill with onlookers, taking silent bets. Happens all the time. How often do you get to watch a life or death moment? I jelly the paddles and plant them on his chest. We start with 200 joules; the aim is to stop the heart, and let it reset itself naturally. I shout “Clear!” but nothing good happens. We up the voltage. No good. “Let him go” the doc says. A decision, just like that. My patient from this morning is a dead guy in the afternoon. I have materially participated in someone’s death, and have no idea what to tell myself.