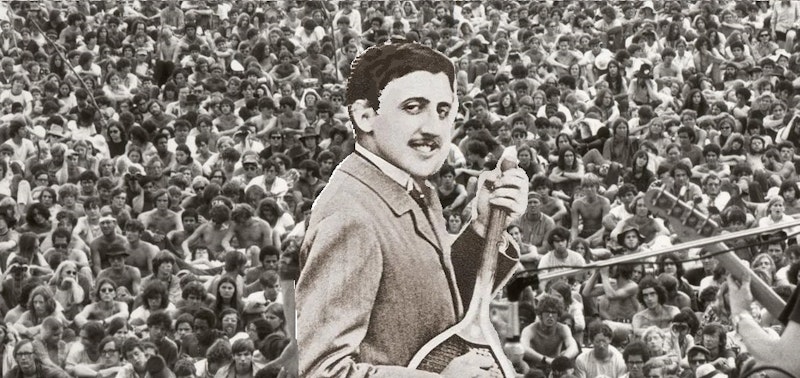

There’s a video on YouTube of Country Joe McDonald discussing the 1969 Woodstock festival. His short performance is featured in the concert film. It starts with his calling out to the immense crowd: “Gimme an F, gimme a U, gimme a C…” continuing until he has the entire crowd screaming out “Fuck.” He then segues into an anti-war song. The moment symbolizes the unity of the crowd in their anti-war sentiments.

What’s interesting about the video is that McDonald, whose subsequent life was greatly determined by those three minutes, says that he can’t recall any of it, it was like he was on automatic pilot, that it just happened like a forgotten dream. Hearing him speak about it, he seems like a victim of a head-on collision, who even years after, can’t recall the event for which he was responsible. It strikes me as a great irony to be absent for one’s own shining moment.

I finished reading Proust’s In Search Of Lost Time about a year ago and ever since I’ve thought about it. There are many possible interpretations. One is that if you wait long enough, anything can happen and probably will. When I read the last volume I was shocked. Not for the prurient events, but because within the economy of the preceding several thousand pages, it seemed like an abrupt turn into a new world. A very familiar world, one which bears a strong resemblance to present times. Up to this point the book had a dream-like quality of memory to it, time suspended, things changed but was no feeling of a specific chronology. In the last volume that all changes, dates are given, the world becomes real, even plebian, the veil is lifted, the dream is over, the magic gone, reality reigns, it’s people in rooms. To create this effect he changes scene. In all the preceding books he’d stayed in just a few well-to-do quarters, private mansions, exclusive hotels and vacation spots. Suddenly he places us in a working-class quarter surrounded by working-class people. Up to this point the book has been filled with millionaires, politicians, famous artists, writers, heiresses and Dukes; the new characters are waiters and bordello owners. And then there’s the final party scene, which is an even greater shock, where Proust’s social world is turned on its head.

There’s a subtext in the book of the impossibility to consciously be where you are when you’re actually there. Thinking and anticipation keeps us distant from ourselves and what surrounds us. Our desires keep us looking at ourselves from the outside, alienated from existence. Life is cumulative. We can’t draw any final conclusions and it’s difficult to say where we are with any certainty because the facts aren’t all in. We operate within a sphere of the incomplete and as-of-yet undefined. This makes life both satisfying and frustrating. When I was 14, a friend of mine asked me about my retirement plans. I thought he was out of his mind. What was the hurry? But maybe he wasn’t so unusual. The bulk of our lives are spent waiting for some event to occur, and he’d just skipped to the end.

A desired event either happens or doesn’t and then we start to wait for another. This gives form to our existence, like one of the old Republic serial movies. We wait, and we’re constantly adding things up as we move along. One of the roles of art is to create experiences which play with the idea of conclusion and completeness. Art provides a fixed perceptual unity, which, unlike our lives, allows for the taking of perspective. I believe we have a psychological need for this as an antidote to the unknown. If life is like a sentence made up of endless subordinate clauses where we wait, either patiently or impatiently, for some meaning to emerge, it only assumes a definite shape at our death, which is the equivalent of the final period. Only then can the eulogy be read.