—September 2, 1965

Eppinger looked at the wall and it was covered with sheets of paper, each one the size of a menu. They’d been gone at with black grease pencil, and you saw discs, shafts, cigar shapes, loops, all marching up and down. Not just one wall, one and almost a half: the rows of sketches filled in a corner and lapped onto the next wall. Eppinger liked that; he wanted plenty to look at.

Having the shapes all crowded there somehow made that part of the room seem weighty and official, as if everywhere should look like that but only this one place had made it. He started counting the sketches but gave up when the figure ran high enough. “That much in four weeks,” he said to the designer. “Not bad.” He pivoted slowly on his heel and looked at the spread. “Okay,” he said. He leaned forward, fingered a sketch, shifted back onto his heel.

The design man half-smiled, held still. The associate producer stood by, and now then he shifted his weight in a way that Eppinger found distracting.

“Bet we’ve got it pinned down,” Eppinger said, to include him. “It’s in there. What do you say, Oscar?”

The associate producer looked at his watch. “That’s where you come in, Ben,” he said.

“I come in everywhere,” Eppinger said evenly. “As I understand it.”

“Got a point there,” Oscar said. “The show is you and you are definitely the show.” He had a loud, barking laugh. Eppinger nodded.

For the next seven minutes the associate producer and the designer listened to the paper rustle. Eppinger hunted through the pictures: it was like his car keys were supposed to be there and they wouldn’t turn up. Twice, in a dull, flat tone, he said, “Shit, I don’t know,” reporting in to himself with bad news. The designer held still.

“Oscar,” Eppinger said. “What do you think of this here?” He leaned his finger against a drawing of what appeared to be a windmill hugging an eggbeater.

“Look,” Oscar said, “whatever you pick, remember we’ve got to get it built.”

Eppinger said nothing to that.

“Got to check about the gun prototypes before the shop closes,” Oscar said, and Eppinger nodded, nose pressed against the wall.

Five minutes of silence followed. The designer didn’t say anything. Then Eppinger stood up, looked about him, found that the designer was his only audience. He shook his head and released a short, sharp burst of air. “Okay,” he said. “Look. We’ve got to get on the trail here. Do you have a pencil? No, a pen.“

The designer hesitated.

“Need a pen,” Eppinger said. He lifted his fingers and then let them drop against his pocket, which was empty. “All right?” he said.

The man hurried to his design bench, returned with a blue Magic Marker.

“Yeah,” Eppinger said, taking it from him. “You know, what we’ve got to do…” He dove in again at the wall.

The Magic Marker squeaked. Eppinger circled a disk. “And over here,” he said, wheeling to find the other sketch he had in mind. He kept wheeling, searched, stood back and hung there for a moment, lost; then he lunged again. “Right,” he said, “right here. We’re looking for this,” and he circled a pylon near the bottom of the wall.

Now and then he would look up and apprise the designer of his thinking: “You see, we’ve got to keep in mind the perimeter” or “I’m looking for two kinds of portals for the docks, because of the different classes of vessel.”

They spent three and a half hours looking at the wall. When the first Magic Marker got too faint, Eppinger threw it aside and the designer ran to get another one. By the end Eppinger had circled 27 cylinders, discs, attachments, shafts, domes, and portals. He pulled away the sheets he liked, held them tight against his hip. Looking at the wall, he got a warm feeling because of all the gaps, the places where he’d grabbed himself a decent idea.

Eppinger held out the clump to the design man. “It’s right in here,” he said. “Start putting these together and you’ll get there.” It was a little before 10 p.m.

The design man took the sheets gratefully. “You see, all of that, that’s new,” Eppinger said. He’d lit another cigarette. “Fuck, I’m tired,” he said, but as if confiding a friendly secret, then went on. “There’s none of that clunky… the Buck Rogers. This stuff, it’s got the—” Eppinger dipped his cigarette in a shallow arc followed by a sharp tilt downward. “That’s the future,” he said. “That look. You know?” And now he looked at the design man, eyes on him for a moment. He wanted to see if he got it.

The design man had been riffling from one sheet to the other. He swung his eyes up now, meeting Eppinger’s as if he had been hypnotized. “Yes,” he said, truthfully.

Eppinger nodded. “The future,” he said. “When you think about it, look, the way life is going to be organized—” And he started to describe the logic of design regarding living arrangements in a space station.

The design man took it all in, the 20 minutes’ worth, and said, “Yes, I think I see.” He was smiling, timid but happy. He managed a dozen words before Eppinger jovially shut him off. “Right there,” Eppinger said. “Look, we’ll have this thing done before you know it.” He added, “Bed is calling.” He had done a day’s work.

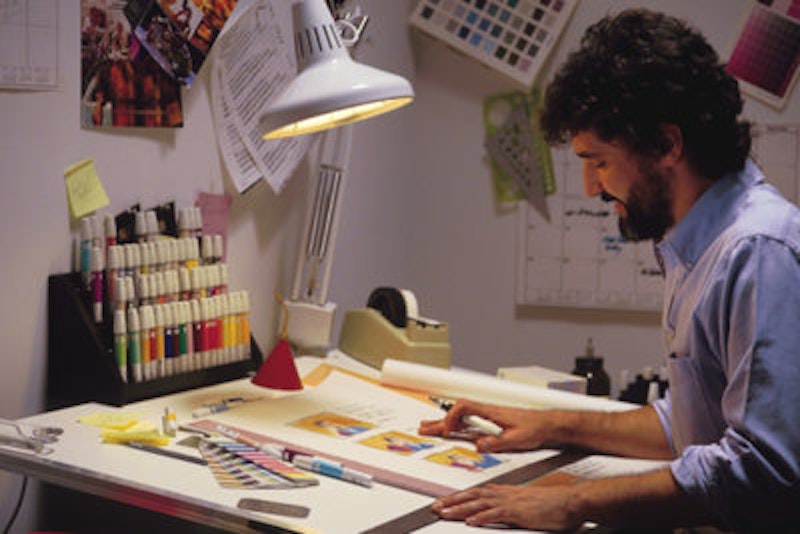

The designer spread the sheets on his worktable, hunched down over them, and started sketching how they might fit together.