What attracts me to the subway is its iconography and signage that preserve styles from decades past. The MTA has unwittingly left a museum under its nose: despite its best efforts to standardize, the old stuff is still down there. Though the NYC subway was not the world’s first, there were others in London and Boston years before construction began here, it was immediately recognized as a tourist attraction.

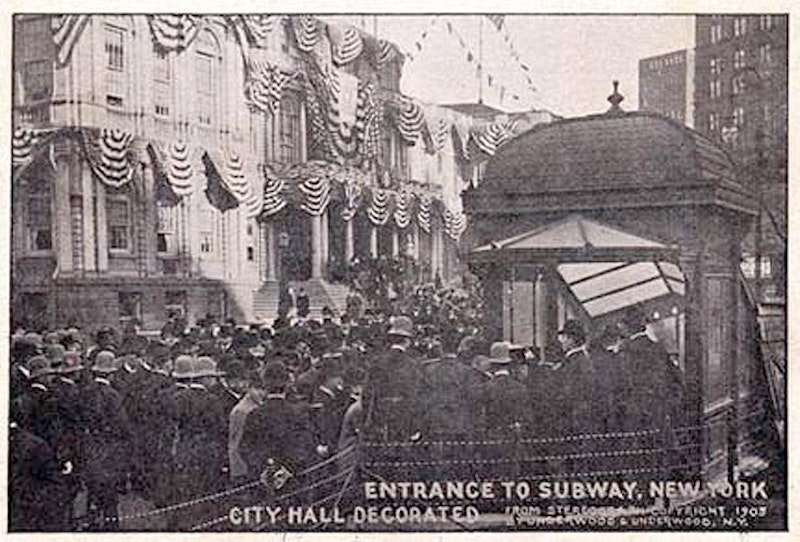

The photo above depicts the crowd outside the station at City Hall on the subways’ opening day, October 27, 1904. The subway was a destination in itself; it eventually freed the streets from the noise and tumult of the elevated. Its first stations were constructed under the aegis of Chief Engineer William Barclay Parsons by the firm of George Heins and Christopher LaFarge. In the early-1900s, architecture was in the sway of both the Beaux-Arts and Arts and Crafts movements, which would play a big hand in the subways’ early days. Beaux-Arts lent its ornate decoration to the early stations, while Arts and Crafts was in many ways responsible for subways leaning on mosaic, marble, brick, ceramics and colorful terra cotta.

Though NYC has potentially the world’s most beautiful subway, it’s been compromised. Water damage; the wear and tear of a clientele numbering in the millions; neglect and apathy; the predations of graffitists and other criminals… they all conspired to send the NYC subway to near collapse. Thankfully, the ascension to power of a wiser management that recognized the NYC subway’s uniqueness and worth was able to pull it back from the brink. Today service is as good as it has been in decades, and subway stations have been restored to original glory, though some still languish in their 1980s decrepitude.

In the subways’ early days, postcard manufacturers such as J. Koehler, Underwood and Underwood, Blanchard Press, and others issued images of the subway in its inaugural era; the original Interborough Rapid Transit (at first in only one borough) ran from City Hall north, west and north again to W. 145th St.

City Hall is unique among all NYC subway stations in its layout and use of color. It stands under the left side of City Hall as you face north, just east of Broadway and Murray St. It featured chandeliers, alternating dark and light green tile created by the Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company, whose tiles also grace the Oyster Bar in Grand Central Terminal, the NYC Municipal Building, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, and the Bronx Zoo Elephant House; the Guastavinos, Rafael Sr. and Jr., from Barcelona, Spain, often fashioned their tiles with criss-cross designs that helped to impart a spatial effect in an otherwise crowded or cramped area. Three skylights, blackened during World War II, allowed natural sun to filter in.

Although turnstiles were first installed in other stations beginning in the 1920s, City Hall never had them at all until it closed in 1945; tickets were purchased in its wooden ticket booth and placed in a ticket chopper.

This postcard, by the Joseph Koehler Company of NYC, shows the tiled arch interior of the City Hall station, which was largely illuminated by skylight, though there were chandeliers holding electric lamps. The oakwood ticket windows are long gone. Before turnstiles and tokens started arriving in the 1920s, patrons would purchase a ticket at the window and hand it to an attendant at the fence separating the fare control area, who’d place it in a ticket chopper. The subway fare was a nickel and remained at that amount until 1948. The low price contributed to the deterioration of NYC’s transit that didn’t begin to be turned around until the late-1980s.

Despite a halfhearted restoration in 1996 in which its original plaques were reinstalled after years at the nearby Brooklyn Bridge station, as you can see, an original brilliantly colored aqua, gold and white nameplate has been compromised. In the past, City Hall has been proposed as a branch of the Transit Museum, but its unlucky position under the seat of NYC government means it will forever be closed due to terrorism fears.

Parts of the 14th St. station are no longer in use. 14th St., an unusual station that twists and turns under Union Square, a topography that requires the platform to use gap fillers similar to those used in the former South Ferry station.

This postcard must’ve been produced after 1910; after that year, the 14th St. express platforms were lengthened, and the side platforms, in use for local trains, were abandoned and covered up with columns and tiles, explaining the lack of decoration or nameplates. Unlike other renovations, those platforms weren’t removed. The sidewalls were originally graced by ceramic eagles likely produced by William Grueby’s Grueby Faience company. Some of the eagles were removed and placed in the mezzanine running above the 14th St. station leading to the exit on the south side of 14th St.

The photos I’ve seen of the ticket booth of the 18th St. station on today’s #6 line show a clock, a feature I haven’t seen at any of the other original stations, though it’s possible clocks were at every ticket booth. When the subway extended IRT platforms after World War II, it was considered redundant to do so here, since it would bring the station’s platforms close to 14th St. or 23rd St.. It was therefore abandoned in 1948. It’s still there in Beaux-Arts splendor, though, covered over by grime and graffiti. Perhaps a way can be found to use these closed subway stations for restaurant or event space, while shielding them from passing subway trains.

The 23rd St. and 28th St. stations on the IRT Lexington present something of a mystery for me. Postcards and photographs of them when they were new, as seen here, show a staircase and a more-or less two-level platform, but I don’t recall the staircase being there now. What happened to it? For 1905, the station strikes me as streamlined and modern, with skylights allowing ample sunlight. Note the paint scheme on the pillars: they were cream white with maroon and dark green. The scheme has been preserved at the IRT Astor Place station.

I was naive until a relatively older age and for some reason I’d thought the trains ran in a tunnel that ran along the river bottoms and the walls stopped the water from rushing in. Only later did I realize that the tunnels ran under the riverbed. The top view is pretty much the same view you get from the Staten Island Ferry front or back, depending on whether you’re leaving or arriving.

The three arches in the middle of the photo are the backend of the 1907 Battery Maritime Building, from where you presently catch the ferry to Governors Island. The tall building in the center is the Singer Tower (1908-1967). The two portals on the left are for the Staten Island Ferry.

This Detroit Publishing Co. card shows the heavy iron and glass entrance and exit kiosks at the 28th St. station at Park Ave. South. Beginning in 1904 the IRT built these large, ornate items, which were cumbersome as sidewalks became more crowded and in the auto age, motorists found them blocking their view. All of them began to be phased out in the 1940s and all had been removed by the mid-1960s. Note there were two different types, one with rounded roofs for entrances, and peaked roofs for exits.

After the IRT was extended to Brooklyn beginning in 1908 postcards were produced showing some of the station stops. The stationhouse shown here, in the triangle made by Atlantic, Flatbush and 4th Ave., still exists and has seen waves of deterioration and revival over the years. When I first saw it in the 1960s it was surrounded by fast food kiosks. After they were removed, the house went through about 30 years of ruin until a renovation in the early-21st century restored it, but made it a glorified skylight with no entrances or exits.

The 5th Avenue El, here shadowing Flatbush Ave., went out of business in 1940.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)