Upon hearing the troubling, if unsurprising, news last Friday that the Baltimore Sun Media Group plans to close the weekly City Paper—an improbable 2014 acquisition by the economically-troubled daily that’s owned by tronc—a couple of old friends who were present at CP’s founding in 1977, said, “40 years. A good run!” Not much comfort for the remaining employees at the current paper, who face unemployment in an unforgiving media climate sooner rather than later. Editor Brandon Soderberg said that until the paper’s officially closed (and why The Sun would continue to operate it until “sometime in 2017” instead of shuttering it now is a mystery; or maybe not, given its knuckleheaded management) there’s a chance someone will buy the weekly. Soderberg is, properly, rallying his staff, but the likelihood of some wealthy man or woman taking on the financial burden of a print paper in 2017 is even more unlikely than current mayor Catherine Pugh morphing into something other than a lifelong political hack.

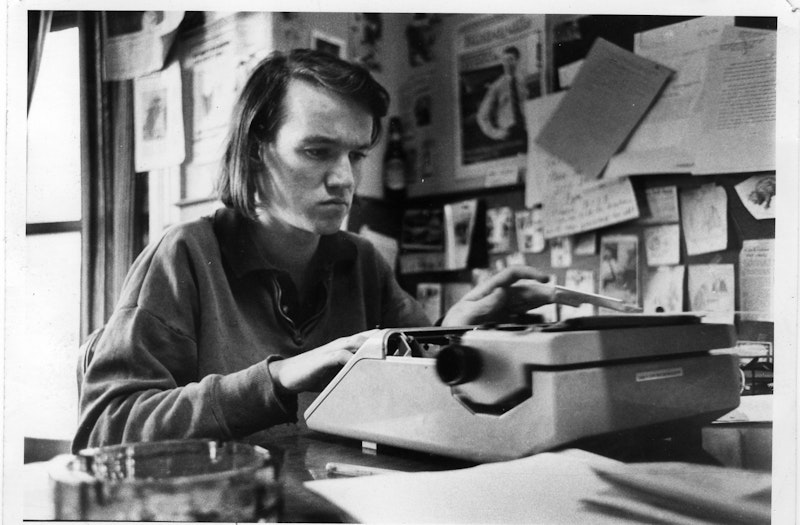

(Pictured above is me in 1978, 23, tapping out on a typewriter an editorial endorsing the citywide referendum on building Harborplace. It’s inconceivable today, but there was a vocal minority against the project that would bring jobs and tourists to the still-ravaged city, and our readers weren’t pleased by this pro-business stance.)

It’s not 1993 any longer, when print media was racking up double-digit profit margins, and weekly newspapers like City Paper were part of that heady mix. Today, consumers of news don’t like to read articles longer than 250 words, if they make it past the headline at all, and readers younger than, say, 35, hardly ever soil their hands with newsprint, instinctually preferring to graze online, seeking websites that confirm their own cultural or political opinions, or simply to marvel over pictures of babies, Trump memes, or prom/wedding/birth/death notices.

My longtime friend Crispin Sartwell, a philosophy professor at Dickinson College, who started writing music articles for City Paper in the early-1980s, then New York Press in the '90s, and now, for Splice Today, figured in an email exchange that this development might cause mixed emotions for me and my partner Alan Hirsch—we owned City Paper until selling it in 1987 to the once powerful Scranton-based Times-Shamrock Communications—but that wasn’t the case, as both of us are 30 years removed from operating the paper in a ramshackle Lower Charles Village rowhouse. The industry as I knew it has been dead for many years now, and another newspaper closing is par for the course. I wasn’t yet 22 when the first issue of City Paper (temporarily called City Squeeze) appeared around the city. I’m now 62—even if ’77 seems like a month ago—and realize, with a more measured point of view than I possessed back then, that if you’re fortunate to live a relatively long life the world turns upside down every 10 years or so.

City Paper, like most weekly papers, was a longshot to begin with: we had little money, zero business acumen, and began publishing in a city far more provincial than today, that had seen freebies come and go and barely noticed them. The staff was long on bravado and raw talent, a willingness to work long hours, and that was about it. I began a column from City Paper’s triumphant 10th anniversary issue in June of 1987, recounting a bleak night, just one of many, when the paper started. It read: “One August night in 1977, exhausted from a particularly fruitless day of selling advertising space, a friend [Craig Hankin] and I darkly contemplated the demise of the fledgling newspaper. What message could we send to the public in the final edition? He suggested, and I instantly agreed, that the front page should read, in 72 point bold type, ‘Fuck You, Baltimore.’ We laughed and laughed and went back to work the next morning.”

City Paper was continually on the brink of insolvency during its first five years—despite often excellent content and photography from, among many others, Joachim Blunck, Jennifer Bishop, Tom Chalkley, Arnold Zwy, Franz Lidz, Eric Garland, Michael Yockel, Phyllis Orrick, John Strausbaugh, J.D. Considine, Craig Hankin, Peter Koper, Ken Sokolow, Mark Jenkins, Moira Crone, and Andrei Codrescu—mostly from a lack of operating capital. On biweekly paydays, staffers would scurry across the street to Maryland National Bank, hoping their checks could be cashed. We were in debt to the IRS for unpaid taxes—no illegal intent, just no cash on hand, and of course the IRS didn’t notify us until huge penalties had accrued—and, after turning a small paper profit in 1980, made the rash decision to start another weekly in Washington, D.C. That was my own hubris, and Alan reluctantly went along, as I did when he came up with an idea. Fortunately we were bailed out by the then-fat and very profitable Chicago Reader in 1982, which bought an 80 percent share and paid us to produce the paper. One of Alan’s best schemes was to trim the size of the tabloid from 16 inches to 13 inches, something I was stupidly against at the start, laughably citing “integrity,” but was quickly won over by the economic benefits. Two weeks later, no one remembered the old size.

We ran a “special” issue on December 14, 1979, a retrospective on the 1970s with contributions from writers all over the country, headlined “Notes From the Malaise.” I re-read it the other day, and it holds up well. In particular, I liked this opening paragraph on a front-page article from James G. Burns: “The '70s didn’t affect me all that much. I just got older and crankier and more cynical [he was 26!], if that’s possible. Had I spent the earlier part of the decade in Vietnam or these past few months in Teheran, perhaps something would have affected me. But I’m always in the wrong place at the wrong time—which is why I’m an amateur hack writer today instead of the celebrated outlaw journalist I dreamed of becoming when I was in high school. Hence the malaise.”

Like most weekly papers, CP was staffed predominantly by people under 30; at least to start off. Today, it’s a terrible time for a precocious writer to enter journalism; not only are jobs very, very scarce, but the Internet has sapped the guts from the profession. The upcoming demise of today’s City Paper isn’t sudden like an airplane or Amtrak crash; rather it’s a long, drawn-out, and incurable disease.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955