A few days ago at the office my son Nicky, hearing a clunker track from Abbey Road on my iPod—“Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” yet another harbinger of Paul McCartney’s gooey side that would define his post-Beatles career—turned down the volume on Howard Stern for a moment and engaged me in a discussion about the group that disbanded 22 years before his birth. He reiterated his strong distaste for Abbey Road—we’ve had this discussion before: he prefers the White Album (yeah, yeah, yeah, sticklers, The Beatles), I go with Revolver—and expressed befuddlement that so many of his contemporaries think that record is just boss. Preaching to the converted—although I have a sliver of fondness for Abbey Road, since a review of it in my junior high school newspaper, The Echo, was my first published byline—I nodded and said the only songs I like from that release are “You Never Give Me Your Money” and “Come Together.” He dissented, pledging fidelity to George Harrison’s “Here Comes the Sun,” which I never cared for.

That led to Nicky wondering why John Lennon is currently taking a lot of flak—news to me—and that Harrison, with the exception of a few songs, is vastly overrated. I wouldn’t go that far, although the rhapsody over his late-1970 triple album All Things Must Pass escaped me at the time and still does. It could’ve made a very decent single LP, highlighted by “Apple Scruffs,” “My Sweet Lord,” “Wah-Wah,” “Beware of Darkness” and “What Is Life.” Actually, that makes half a decent album, sort of like the first solos from Lennon and McCartney.

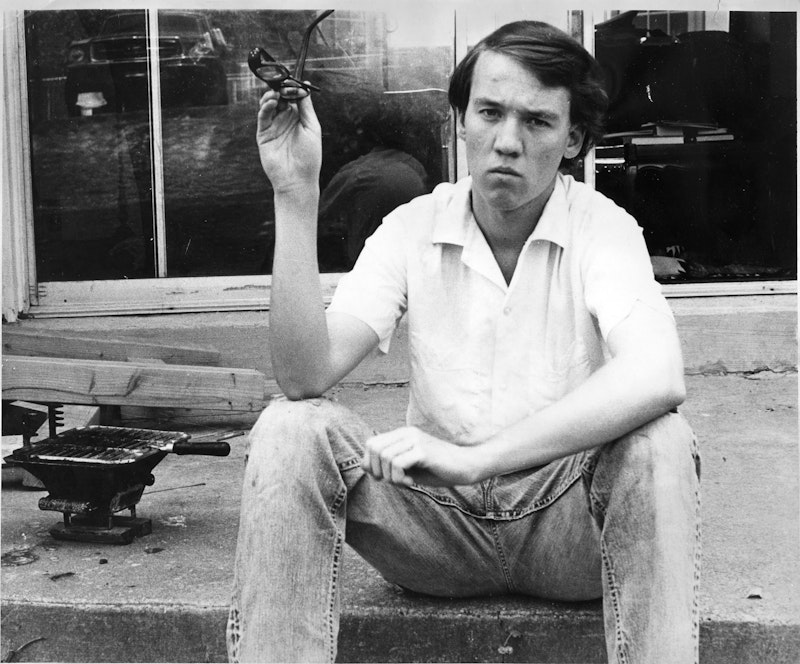

As these conversations progressed—a rambunctious bout of procrastination—we wound up in 1974, when I was 19 and a college sophomore (the picture above, with an uncharacteristic scowl on my face, was taken outside a house I rented with four other fellows in September of that year). Told Nicky I missed two concerts that year that I wish I’d attended: David Bowie in his new blue-eyed soul persona (I couldn’t get out of work that night) and Harrison a month or two later. The first big tour by an ex-Beatle, I was planning to go, but reports of Harrison’s ragged voice and too much Ravi Shankar led me to pass, even though I loved the song “Dark Horse,” from the album he was promoting. I regret it now, since I was too young to see The Beatles before they stopped touring in ’66, never had interest in a Wings show, and was nowhere in the vicinity of any of Lennon’s ad-hoc shows. Missing Harrison, just 33 at the time, is a hole—as we all have—in my concert history, which, by and large, is a pretty good one.

But let’s think about 1974, since it was a great year to be alive—although I’d guess when you’re 19, any year fits that bill—with all the cultural and political events of the time. Watergate had wrapped up officially when Jerry Ford inexplicably pardoned Richard Nixon—a shocker I’ll never forget upon picking up a copy of Baltimore’s Evening Sun in early September with the banner headline screaming the news—Patty Hearst was on the lam, pictured in the garb of her Symbionese Liberation Army kidnappers, and the drinking age in Maryland was temporarily lowered to 18, which was crucial to me, since I’d get carded at any bar until I was about 25.

The house I shared on Belvedere Ave. with Joe Griffith, Fred Lohr, Grant Abrams and Tom McQuilling was a ways from the Johns Hopkins campus—and with no car, I either mooched rides, took the bus or hitched back and forth to school—and, unlike places I’d subsequently wind up, was fairly modern and even had a back yard. We’d settled in before classes started, and I remember one day the five of us cruising in Tom’s white convertible, speeding, and the wind whipped my long hair ferociously (I got a short haircut the next day) on the way to IKEA to buy supplies for the joint. I didn’t quite understand the necessity of such purchases—milk cartons were fine for books and records—but the suburban ride was a lot of fun, with Tommy blasting, and singing along badly with, Barry White’s “Can’t Get Enough of Your Love, Babe.” I’d have to say the five of us had diverse musical tastes, which we shunted aside: when I couldn’t take the downstairs stereo playing the new Grateful Dead record or Eric Clapton’s awful 461 Ocean Boulevard, I retreated to my room and listened to Dylan boots, Bowie and Steely Dan on my cassette player.

Tom was the de facto captain of the house: I think he originally found it (I rounded out the group needed for the rent) and was the master organizer, including dunning each of us for shares of the grocery bill. One time we had a small row over that: I protested that since I ate dinner at my place of work, I was overcharged, and since dough was tight this was no small matter. We settled amicably, as I was allowed out of the “meal plan,” an option Tom refused to believe I’d take, but after a day or two of testiness—normal roommate stuff—there were no hard feelings.

And though I haven’t seen Tom in decades, I’ll always have a soft spot for the guy. In the early hours of one September morning, around five, Tom—who, naturally, had a phone extension in his room—woke me up, saying I had a phone call. “It’s your brother, Russ,” he said in a hushed tone, “and I don’t think it’s good news.” It wasn’t: an infant niece of mine had passed away suddenly during the night, and naturally it was hard to digest. Tom, in a Thurston Howell III bathrobe, and groggy, said, “Look, I know you’ve got some calls to make, so stay in my room for privacy.” It was an act of kindness that I’ll never forget.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955