The artist Vincent Paronnaud, who works under the name Winshluss, has done some amazing things. His early comics, Smart Monkey and Welcome to the Death Club, harkened back to the glory days of Gary Panter and Charles Burns. Persepolis, which he co-directed with creator Marjane Satrapi, was one of the best animated films in ages: it won big at Cannes, then lost the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature to Ratatouille—once again demonstrating that in these insipid United States, there can never be any accounting for taste.

But most importantly, at least to me, Paronnaud produced the definitive adaptation of Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio. That book, yet another vestige of a 19th century that treated children now regarded as precious to the point of being priceless like the miserable, beaten-down laboring adults they would quickly become, haunted my childhood. Pinocchio, a magical log carved into the shape of a boy by the starving, bread-deprived puppeteer Geppetto, strides boldly into Collodi’s bizarro Tuscan landscape, whereupon he alternates becoming making stupid decisions that harm people who care about him (he immediately kills the Talking Cricket who attempts to warn him about the dangers of bad behavior, and is haunted thereafter by the cricket’s ghost!) and being duped into performing wretched deeds by awful, self-interested slimebags who themselves wind up maimed or dead.

This is not the goofy, happy world of Walt Disney—who profited from sanitizing these sadistic old fairy stories, rounding hard edges into soft curves for 20th century boys and girls—and any proper adaptation or updating of it ought to be nastier, not nicer, than the original. Roberto Benigni’s 2002 film, Pinocchio, was universally despised by critics, but not for the right reasons: it suffered from an excess of horrifying, The Hobbit-quality pancake makeup and a risible dub, but it was mostly faithful to Collodi’s rambling, plot-less picaresque, right down to the gawky, unattractive Benigni playing the titular boy-puppet (look at the illustrations that accompany contemporary editions of The Adventures of Pinocchio—the likeness is uncanny). As far as I can determine, live-action children’s fantasies must follow the Beauty and the Beast blueprint or face the wrath of a low Rotten Tomatoes score: some “adulting” to mature the narrative—but only a pinch, and nothing dark!—in the service of a narrative rehash staffed by comely rising-star actors.

Who, after all, would want to get down into the dirt and shit of the old fairy stories—as in Charles Perrault’s 1697 Cinderella story, Cendrillon, wherein the main character’s stepsisters give impressionable readers a true dose of adult self-interestedness when those deluded women straight-up slice off their heels and toes, splatterhouse cinema-style, to fit in the coveted glass slipper that holds the promise of untold wealth and privilege.

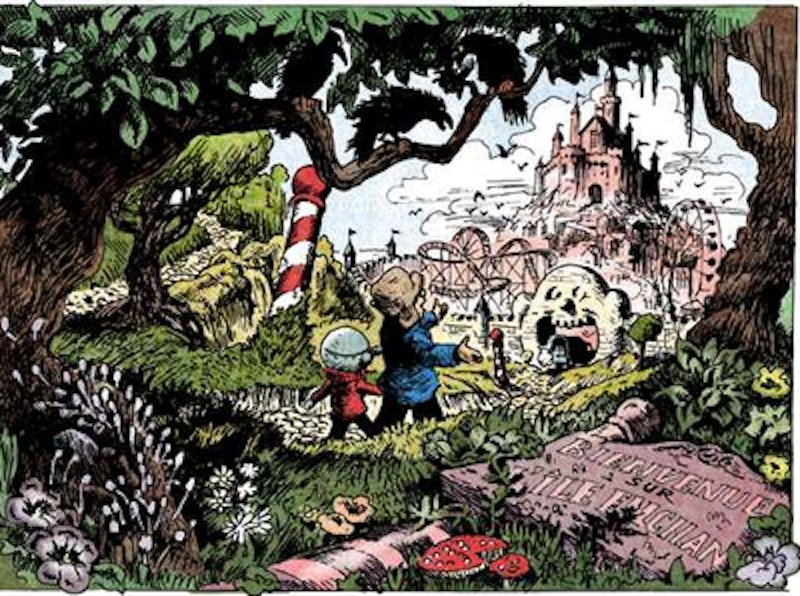

So here’s where Paronnaud’s Pinocchio comes in. The marketing for a work like this, if one were to market it all, might go something like “Pinocchio as you’ve never seen him before,” because in this version Pinocchio is a tiny metal war machine that accidentally incinerates Geppetto’s buxom, lascivious wife while she is attempting to pleasure herself atop his flame-throwing nose. But this shocking scene—one among many in a book that sees a roving mechanical eyeball embed itself in a beggar’s blind socket and a bloody coup lead to mass executions throughout Toyland—is actually par for the course. Yesterday’s gruesome children’s stories are today’s underground comics, a sign of the gradual but sweeping infantilization of expression: once we were told everywhere and often that life is unfair to the point of being terrible, whereas today we are constantly sharing our slacktivist outrage upon discovering (and then rediscovering!) that this is so.

Then there is the matter of Paronnaud’s art, a critical factor in a largely wordless work. Much of the corporate, pre-packaged comics fed to us during our Gen-X youth involved some cynical collaboration between illustrator and writer, with a handful of top hack authors scripting all the expensive super hero properties. I grew up consuming this colorful junk food, bingeing on it alongside bags of cheese puffs, but it ultimately amounts to so much insubstantial, soulless work product. Comics as a medium flourish under the discerning eye of a single great creator, a George Herriman or Winsor McCay showing us a story through their art rather than telling it to us through dozens of distracting captions and thought balloons.

Paronnaud does the same here, designing an adventure that is by turns propulsive and repulsive. Every character introduced is flawed; every flawed character eventually receives his or her just desserts. For all its edgy, underground trappings—Jiminy Cockroach is a John Fante-style dirty realist hipster who has taken up residence in Pinocchio’s empty head—the work largely replicates the moral arc of Collodi’s meandering original. Few well-meaning adults will share this book with their children, probably because they’re unprepared for it themselves.