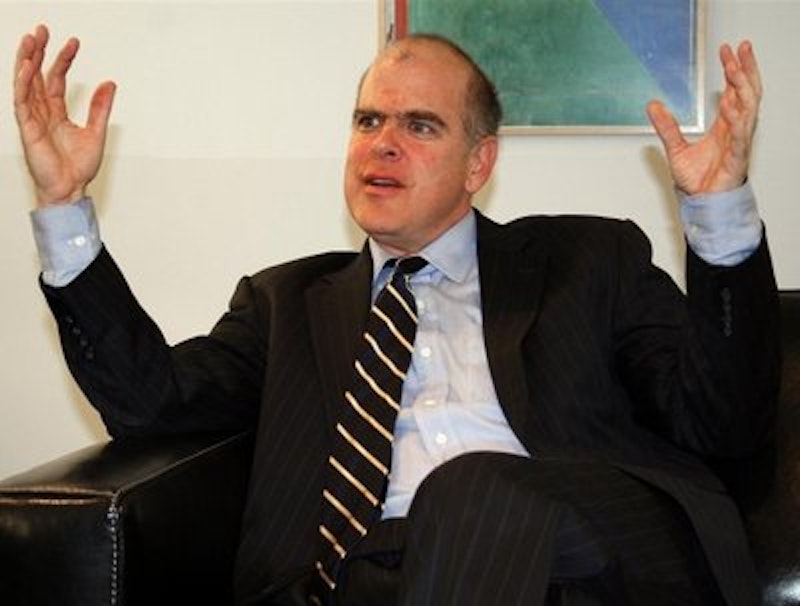

So, has eminent journalist Christopher Caldwell, after a bracing period of independence, backslid into the obsessions of the neocons?

Readers will remember that Caldwell, long associated with the neocon journal The Weekly Standard, last year roused himself to a break with his genocidally anti-Russian masters at that magazine. He went so far as insist, in so many words, that the peace-loving Great Russian people have the right to exist.

For such a right the Great Russians indeed have; and more, they have a right to live unharassed in the lands that God and History have bequeathed them, including Crimea and Little Russia (the soi disant “Ukraine”). Those are—should be—integral parts of the Great Russian body politic, parts that were tragically sundered from its holy unity at various times in history by the wiles of Western imperialism, and by the homo-imperialist sword.

Well, Caldwell’s bravery—his moral clarity, to use a word much loved by Jewish and other warmonger journalists during the run-up to the Iraq war—didn’t last long, at least according to Brother Aiden, my partner at our Benedict Option homestead here in Indiana. Recently Aiden shuffled into my workroom, brandishing a copy of a speech that Caldwell made this winter. Aiden had underlined this passage, and he read it aloud to me now: “According to the official United States account, Russia invaded its neighbor after a glorious revolution threw out a plutocracy. Russia then annexed Ukrainian naval bases in the Crimea. According to the Russian view, Ukraine’s democratically elected government was overthrown by an armed uprising backed by the United States.”

A couple sentences later, Caldwell adds the pay-off: “Both of these accounts are perfectly correct.”

When Aiden came in, I was mending the block that pivots the harrow, in preparation for Mother’s fieldwork the next morning, when the sun would first rise over the new rye. A farm wife rises even earlier than usual in summer; it must be so, because there’s so much to be done. But Mother consoles herself with the sanctity of her labor; like the redeemed hero, Nekhlyudov, of Tolstoy’s Resurrection, she rises with alacrity to the good work of God’s day.

“It’s not true,” Aiden keened, rocking back and forth on his sandal, fingering his sparse beard. “Both those accounts aren’t perfectly correct. There was no ‘glorious revolution.’ The Ukrainian—the Little Russian—side is wrong, John.” He started to stutter, as he tends to when worked up. “There can’t be two truths, John. There can be only the one truth. The revealed Truth. God’s truth.”

Overwhelmed by a sudden melancholy, I bade Aiden leave, and returned to my work.

•••

Melancholy, not anger.

I find it hard to rage at Caldwell for this apparent moral equivalence between the clean Truth of the Russians and the propaganda of the Kiev Junta.

First, it might have been much worse. Caldwell calls the Yanukovych government that the Soros-funded Kiev fascists overthrew a “plutocracy.” That’s false. Yanukovych is an honest son of the Ukrainian working class, which to this day lends him their firm support.

But it’s also mild given the other epithets that the neocons, the Americanist jingoes, the anti-Russian fanatics, the Zionists, and the Ukrainian Diaspora Nazis have thrown at the Yanukovych government in the past. Had Caldwell truly embraced the Kiev Junta’s lies, he wouldn’t have stopped with “plutocracy.” He would have repeated the insane lies that the anti-Yanukovych forces, both in the West and in Little Russia, have motivated over the years.

He would have mentioned, for instance, the non-existent “political murders” which the fascists falsely accused Yanukovych of committing. He would have bleated about the endless smaller-scale “violence” of the Yanukovych government, repeating the Soros fascists’ tall tales about the brutalization of innocent protestors, some of them girls. He would have squealed out the usual falsehoods about how the Yanukovych government was horrifying even by Ukrainian and post-Soviet standards.

That he didn’t is proof of Caldwell’s essential wisdom and goodness, and that he is not as far gone as Aiden feared.

But my calm is also the result of the fact that I’m becoming, after great effort, a better Christian. Not only in the sense that I no longer invariably confront injustice by flaring up into a prideful anger, but also in the sense that I am more comfortable with the ambiguity of the sort that Caldwell trafficks in here.

Indeed, a comfort with ambiguity is one of the traits that Russian Orthodoxy instills in its faithful. Sacramental to its core, the faith demands not just an intellectual interest in, but also a visceral imaginative confrontation with, that founding ambiguity of the Christian tradition: the Word made flesh, the Godhead become man—O most precious man!—so that he could suffer, and die.

Whatever Caldwell’s small trespasses against the Truth may be, I must forgive them, just as I hope God will forgive me.