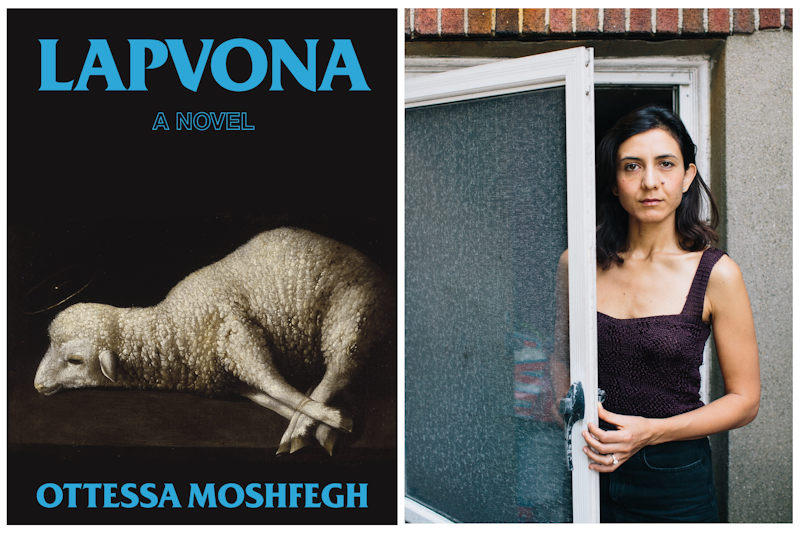

“If he played it well, he might become a saint, he thought. Like Joseph. He’d better act like one, he knew, but it was so boring. It was terribly depressing.” The idiot feudal lord Villiam in Ottessa Moshfegh’s new novel, Lapvona, sums up the author’s body of work so far with these thoughts towards the end. All of Moshfegh’s protagonists, from the titular McGlue and Eileen, to the walking pharmacy without a name of My Year of Rest and Relaxation, to the gleefully petty and bitter Vesta Ghul of Death in Her Hands, are bitter and cynical people. Her collection of short stories, Homesick for Another World, remains her best book, and while Lapvona isn’t her masterpiece (nor a book that’s easily optioned for movies and television like My Year of Rest and Relaxation and Eileen), it’s Moshfegh’s biannual transmission. She’s the best active American novelist, and her steady output and confidence is encouraging. There aren’t many real authors left.

Lapvona is a tough sell for anyone who doesn’t like the Middle Ages or fantasy novels. The work of J.R.R. Tolkien and George R.R. Martin is none of my business. But this is a new Moshfegh book, and once you get over the names and the miserable setting, her voice emerges. Many of her short stories are in the third person, but this is her first novel without a first-person narrator, and her prose suffers for it. Lapvona takes place in the titular fictional village, a place with a distinct medieval milieu but historical figures—just the dressing. Characters from the inbred and orphaned Marek, to the charlatan priest Father Barnabas, to the 100+-year-old mystic and healer Ina speak in modern vernacular. Moshfegh has conjured Lapvona as a miniature Hell on Earth, where everyone is illiterate, unhealthy, violent, and “pious”: slaving away for Villiam in his manor above them, taking all their crops and water, and sending in bandits whenever rumors begin to spread.

Moshfegh’s characters are compelling enough to forget that her writing line-by-line here isn’t as strong as any of her previous novels. At the same time, Lapvona is a deliriously funny book and so dark and over the top evil that everyone’s misery becomes hilarious. Everyone in this book is a disloyal idiot without any real regard for God or the people around them. More than anything else, I was reminded of Salò—the Pasolini film, not the Marquis de Sade’s writings, which Moshfegh has cited before. There’s no political allegory or context to the cruelty in Lapvona, so when Villiam makes his servant Lispeth swallow grapes wiped with Marek’s filthy ass, it’s merely an empty, albeit very amusing, spectacle of cruelty. Pasolini transposed de Sade’s book to 1944 Italy, and by collapsing time between 18th-century libertines, the fascists of World War II, and the hippies and youth of the late-1960s and early-1970s, he produced a much more powerful and resonant work than its source material.

However vulgar and void of anything other than reveling in the potential of human cruelty, Lapvona never struck me as a cruel book by a bitter, bigoted person; nor did any of Moshfegh’s other books. Nearly a decade into her career as a published author, Moshfegh is suffering a backlash from jealous critics and people who want her career, her ambition, her capacity, and her talent. They’ll never have it. I can only take pure critics so seriously—they’re all failed artists, or people who never understood what it’s like to be an artist and never will—and while Andrea Long Chu’s recent “takedown” of Moshfegh in Vulture was well-written, it had nothing in it.

What can Chu pin on Moshfegh? “The self-hating narrator of Moshfegh’s experimental novella McGlue, set in 1851, makes lavish use of the word faggot, despite the fact that its homophobic sense is not attested until the 1910s. Moshfegh has a similarly blithe relationship to physical deformity: Marek, a child of incest, has a crooked spine, a protruding rib cage, and a distorted skull as well as what we moderns might call an intellectual disability. Moshfegh herself might call him retarded, a word that several of her characters brandish like a tiny flag of rebellion.” She starts the next paragraph noting, “To be fair, Moshfegh has never tried to defend her characters on moral grounds,” invalidating all of the above. Moshfegh’s writing is so electrifying because she writes about real people in the real world: cruel, cynical, indifferent to suffering. Chu’s article is filled with petty assumptions about Moshfegh, how she views herself, and how she views others. Her characters are nasty people: the world is full of them. And they’re not uncomplicated people.

Even pettier are the insults towards Bret Easton Ellis and Moshfegh’s fondness for American Psycho. Besides trying to make her guilty by association (she’s been a guest on his podcast), Chu calls Ellis a “sundowning reactionary,” the latter of which is true, but “sundowning”? Look to the White House for that. Ellis has a new novel coming out in January and remains widely read and influential in pop culture, something that can’t be said for any other living writer besides J.K. Rowling. Moshfegh and contemporaries like Sally Rooney and Tao Lin remain big fish in a small pond, modern publishing. Did you know that Jonathan Franzen put out a new book last year? I didn’t until I got it for Christmas.

So of course the resentment was bound to burst. Lapvona isn’t a fun novel to read if you lack the capacity to laugh at man-made misery and our eternal stupidity and cruelty towards each other. Moshfegh doesn’t single out Marek and make a point of his being a product of incest—that’s revealed halfway through—on the contrary, she describes everyone in this book with equal contempt and disgust. It never becomes one-note, but Chu is right in that there is something missing here that’s in all of her other novels. Sam Sacks in The Wall Street Journal slammed the book and asked, “When is this woman going to grow up?” It’s a sexist comment that likely wouldn’t apply to someone like John Boyne, a decade older than Moshfegh and far more juvenile and insipid in his writing. I don’t think there’s another American novelist that not only understands but is willingly to explore how petty and mean people are every day, in their thoughts, speech, and actions.

She just puts a mirror up, she doesn’t judge. Apparently, that’s too much for some people. Or maybe they just want a book deal, too.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith